Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

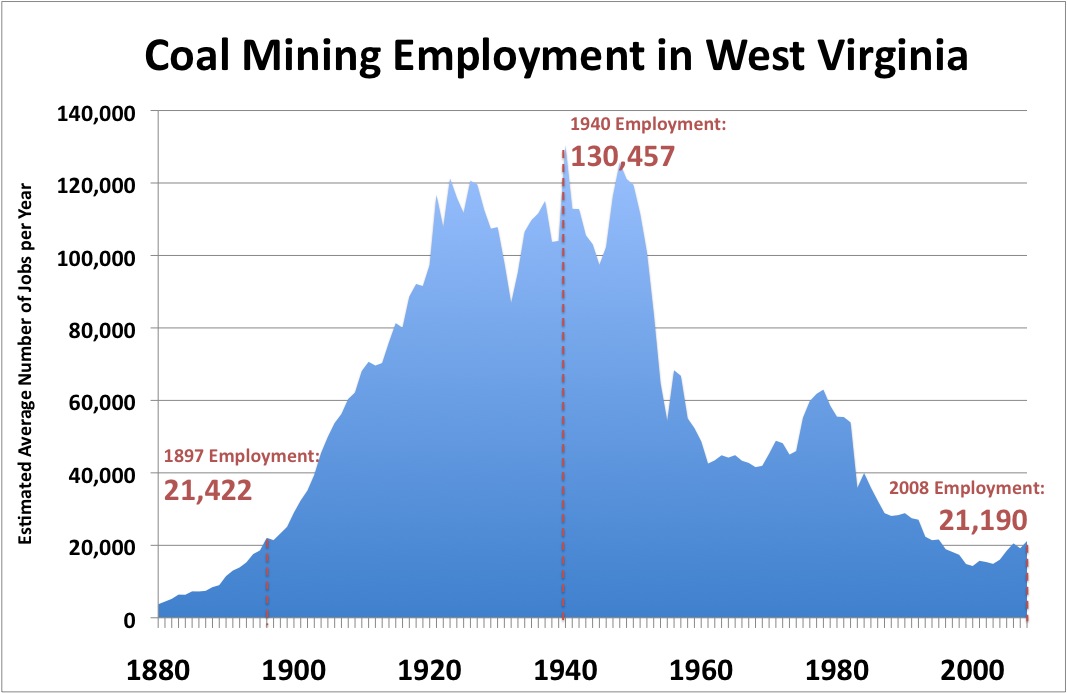

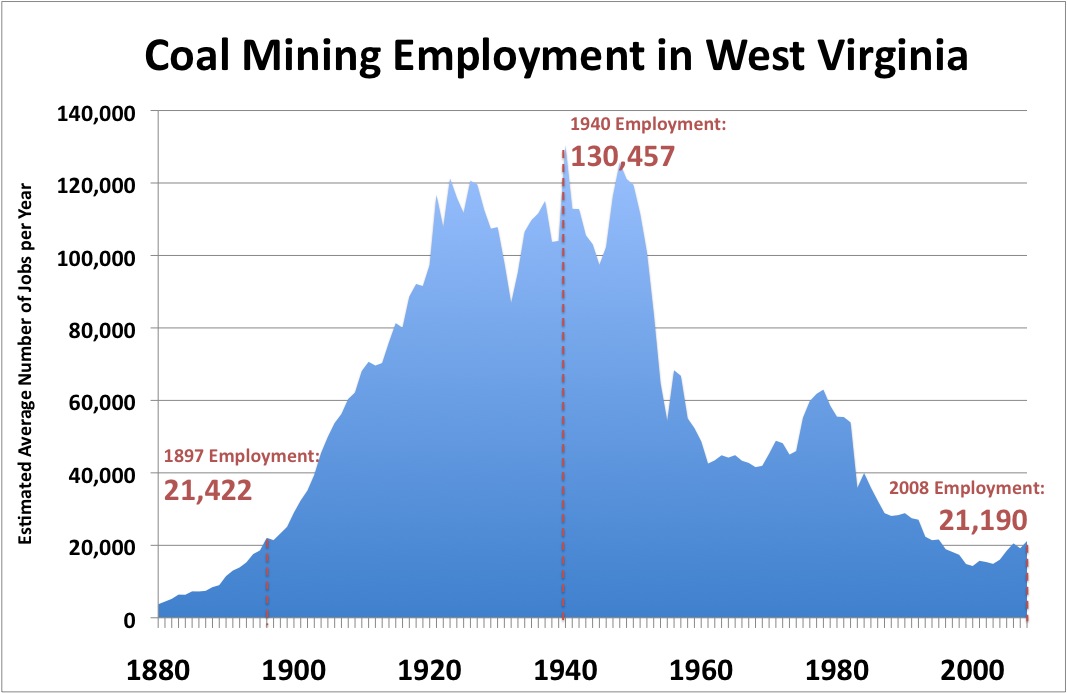

That’s what readers of a NYT article on support for Trump in West Virginia must be wondering. The piece told readers that Trump was promising to bring back the coal mining jobs to the state. While West Virgina used to have many more jobs in coal mining, that was decades ago.

Employment in coal mining had fallen from a peak of more than 130,000 in 1940 to just over 21,000 in 2000, roughly its current level. Employment did rise somewhat in the last decade, reaching 35,700 in December of 2011. (This was a bit less than 5.0 percent of total employment in the state.) However, it began to decline back to its current level the following year, largely due to the availability of cheap natural gas from fracking.

It’s not clear what Trump’s reference point is in his promise to bring back mining jobs. He could mean the peak hit during President Obama’s first term in office, which would re-employ roughly 14,000 miners. It’s not clear who would use the coal — Trump has not indicated that he wants to restrict fracking — but few thought that West Virginia was thriving in 2011.

It is possible that Trump is referring to the more distant past when West Virginia had more than 40,000 jobs in coal mining, but this would mean going back to the 1970s, more than 40 years ago. The main reason for the decline in coal mining jobs over the next decades was increased productivity in the industry, as strip mining replaced underground mining. If Trump intends to restore the number of jobs to the pre-1980 level then perhaps he would ban more efficient strip mining and make the industry rely exclusively on underground mining again.

Note on Source:

Several comments ask about the source for the figure. It comes from the website Appalachian Voices, which I gather is a community organization in West Virgina. Unfortunately, I could not find their source, but since it follows closely data from the BLS for mining employment (which can include mining of other minerals), I felt comfortable using it. (Those data are available in their discontinued data series.) Sorry about leaving it out initially. As far as the years since 2008, these data are available from BLS in the Current Employment Series giving state level data. This series goes up through June of 2016, but only as far back as 1996.

That’s what readers of a NYT article on support for Trump in West Virginia must be wondering. The piece told readers that Trump was promising to bring back the coal mining jobs to the state. While West Virgina used to have many more jobs in coal mining, that was decades ago.

Employment in coal mining had fallen from a peak of more than 130,000 in 1940 to just over 21,000 in 2000, roughly its current level. Employment did rise somewhat in the last decade, reaching 35,700 in December of 2011. (This was a bit less than 5.0 percent of total employment in the state.) However, it began to decline back to its current level the following year, largely due to the availability of cheap natural gas from fracking.

It’s not clear what Trump’s reference point is in his promise to bring back mining jobs. He could mean the peak hit during President Obama’s first term in office, which would re-employ roughly 14,000 miners. It’s not clear who would use the coal — Trump has not indicated that he wants to restrict fracking — but few thought that West Virginia was thriving in 2011.

It is possible that Trump is referring to the more distant past when West Virginia had more than 40,000 jobs in coal mining, but this would mean going back to the 1970s, more than 40 years ago. The main reason for the decline in coal mining jobs over the next decades was increased productivity in the industry, as strip mining replaced underground mining. If Trump intends to restore the number of jobs to the pre-1980 level then perhaps he would ban more efficient strip mining and make the industry rely exclusively on underground mining again.

Note on Source:

Several comments ask about the source for the figure. It comes from the website Appalachian Voices, which I gather is a community organization in West Virgina. Unfortunately, I could not find their source, but since it follows closely data from the BLS for mining employment (which can include mining of other minerals), I felt comfortable using it. (Those data are available in their discontinued data series.) Sorry about leaving it out initially. As far as the years since 2008, these data are available from BLS in the Current Employment Series giving state level data. This series goes up through June of 2016, but only as far back as 1996.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In his Washington Post business section column Gene Marks made a classic journalistic mistake: he reported what people claim to be the case as fact. Specifically, he reported that employers are curtailing hiring and increasing part-time employment in response to Obamacare. In fact, the basis for this assertion is a survey of 200 business executives by the New York district Federal Reserve Bank.

There are two basic problems here. The business executives may be inclined to say they are cutting jobs or increasing part-time work because of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), even if it’s not true, because they don’t like the ACA. The other problem is that they may not know the exact effects of the ACA (actually, no one does), so their response may be based on factors that are not attributable to the ACA.

Specifically, the survey indicated that the executives were responding to a large increase in insurance premiums this year. However, the rise in premiums had been quite low in prior years. It would be difficult to determine how the path of health care costs has been changed by the ACA, but it is indisputable that the growth path has been considerably slower than was expected when the ACA was passed in 2010. So unless these executives can somehow determine that they are paying more for insurance today because of the ACA, they actually don’t have a basis for saying that their response to the latest rise in premiums is a response to the ACA.

Economists tend to look at what people do rather than what they say. In this category, the data tell a story that is the opposite of what is indicated by the survey. Job growth has been very fast since the ACA went into effect. In addition, the number of people involuntarily working part-time has fallen sharply. It is down by 23.5 percent since the exchanges and Medicaid expansion went into effect in January of 2014.

There has been a substantial increase in the number of people choosing to work part-time, notably young parents. (These are presumably parents of young children, but we only have data on the parents’ ages.) This is one of the intended effects of Obamacare. By allowing people to get insurance from outside of employment, Obamacare made it possible for many parents to get insurance without working at a full-time job that provides health care as a benefit.

It is interesting to know what business executives have to say about the impact of Obamacare, but it is a serious error to report this as truth.

In his Washington Post business section column Gene Marks made a classic journalistic mistake: he reported what people claim to be the case as fact. Specifically, he reported that employers are curtailing hiring and increasing part-time employment in response to Obamacare. In fact, the basis for this assertion is a survey of 200 business executives by the New York district Federal Reserve Bank.

There are two basic problems here. The business executives may be inclined to say they are cutting jobs or increasing part-time work because of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), even if it’s not true, because they don’t like the ACA. The other problem is that they may not know the exact effects of the ACA (actually, no one does), so their response may be based on factors that are not attributable to the ACA.

Specifically, the survey indicated that the executives were responding to a large increase in insurance premiums this year. However, the rise in premiums had been quite low in prior years. It would be difficult to determine how the path of health care costs has been changed by the ACA, but it is indisputable that the growth path has been considerably slower than was expected when the ACA was passed in 2010. So unless these executives can somehow determine that they are paying more for insurance today because of the ACA, they actually don’t have a basis for saying that their response to the latest rise in premiums is a response to the ACA.

Economists tend to look at what people do rather than what they say. In this category, the data tell a story that is the opposite of what is indicated by the survey. Job growth has been very fast since the ACA went into effect. In addition, the number of people involuntarily working part-time has fallen sharply. It is down by 23.5 percent since the exchanges and Medicaid expansion went into effect in January of 2014.

There has been a substantial increase in the number of people choosing to work part-time, notably young parents. (These are presumably parents of young children, but we only have data on the parents’ ages.) This is one of the intended effects of Obamacare. By allowing people to get insurance from outside of employment, Obamacare made it possible for many parents to get insurance without working at a full-time job that provides health care as a benefit.

It is interesting to know what business executives have to say about the impact of Obamacare, but it is a serious error to report this as truth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

People don’t expect to see honest debate on economic issues on the opinion pages of the Washington Post, which is why it is not surprising to find a column from Charles Lane trashing Bernie Sanders and his wife for buying a $575,000 vacation home in Vermont. While Lane indicates that he thinks it is okay that they buy this home, he thinks it somehow contradicts Sanders’ self-described socialism. At best, this claim shows how utterly ignorant Lane is of what Sanders said throughout his campaign.

Just to start with the basic economics, Sanders pay as a senator is roughly $175,000 a year. Jane Sanders, his wife, is also a professional can be expected to earn somewhere in that range. This would give them a combined income of $350,000 a year. That is the edge of the 1.0 percent (a bit below), but obviously better off than the vast majority of people in the country. If they took out a $460,000 mortgage (80 percent of purchase price), the monthly payments would be $2,200, certainly well within affordability given their incomes. So there is zero reason to believe that this home purchase implies secret money or some sort of illicit activity.

So the question is whether there is something inconsistent with the Sanders earning $350,000 a year and the views he espoused on the campaign. If so, it is difficult to see what it would be. Sanders said that he wanted to raise taxes on the rich, he never said that he thought everyone should make the same amount of money regardless of how hard they worked or their talents.

It is of course convenient for people who don’t want to see the issue of higher taxes on the rich be discussed to convert the debate into one on radical egalitarianism. However, the latter has nothing to do with Sanders’ campaign positions. One would hope that the people who write columns for the Washington Post would at least know that much about the Sanders campaign.

Note: For my part, I am less a fan of higher taxes than ending the government interventions (e.g. patent monopolies, corrupt corporate governance system, and Wall Street favoritism) that allow for ridiculous pay checks in the first place. Thanks to rigged markets, partners in hedge funds and private equity funds (think Mitt Romney) can make more in a day than the Sanders earn in a year. But you’ll have to wait for my book this fall to get the full story.

People don’t expect to see honest debate on economic issues on the opinion pages of the Washington Post, which is why it is not surprising to find a column from Charles Lane trashing Bernie Sanders and his wife for buying a $575,000 vacation home in Vermont. While Lane indicates that he thinks it is okay that they buy this home, he thinks it somehow contradicts Sanders’ self-described socialism. At best, this claim shows how utterly ignorant Lane is of what Sanders said throughout his campaign.

Just to start with the basic economics, Sanders pay as a senator is roughly $175,000 a year. Jane Sanders, his wife, is also a professional can be expected to earn somewhere in that range. This would give them a combined income of $350,000 a year. That is the edge of the 1.0 percent (a bit below), but obviously better off than the vast majority of people in the country. If they took out a $460,000 mortgage (80 percent of purchase price), the monthly payments would be $2,200, certainly well within affordability given their incomes. So there is zero reason to believe that this home purchase implies secret money or some sort of illicit activity.

So the question is whether there is something inconsistent with the Sanders earning $350,000 a year and the views he espoused on the campaign. If so, it is difficult to see what it would be. Sanders said that he wanted to raise taxes on the rich, he never said that he thought everyone should make the same amount of money regardless of how hard they worked or their talents.

It is of course convenient for people who don’t want to see the issue of higher taxes on the rich be discussed to convert the debate into one on radical egalitarianism. However, the latter has nothing to do with Sanders’ campaign positions. One would hope that the people who write columns for the Washington Post would at least know that much about the Sanders campaign.

Note: For my part, I am less a fan of higher taxes than ending the government interventions (e.g. patent monopolies, corrupt corporate governance system, and Wall Street favoritism) that allow for ridiculous pay checks in the first place. Thanks to rigged markets, partners in hedge funds and private equity funds (think Mitt Romney) can make more in a day than the Sanders earn in a year. But you’ll have to wait for my book this fall to get the full story.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

President Obama is working hard to push the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), going around the country promoting the pact. He must want Congress to approve it before he leaves office.

That much would be obvious to anyone. But Politico uses its incredible mind reading ability to go a step further. It tells us:

“Obama has been unwilling to abandon a deal that he regards as central to his legacy.”

The rest of us might be able to know that Obama says that he regards the TPP central to his legacy, but lacking Politico’s mind reading skills we wouldn’t know that he actually does regard the TPP as central to his legacy. Since President Obama is a politician, we know that he doesn’t always say exactly what he thinks, so we may not know whether or not he regards the TPP as central to his legacy.

We could believe that the is pushing the deal as a favor to the powerful business interests that helped to negotiate the deal, like the pharmaceutical industry, the entertainment industry, and the financial industry. These industries are expected to be major donors to Democratic campaigns this fall.

Of course, it would be difficult to get approval for the TPP based on the argument that it would benefit contributors to the Democratic Party. Since President Obama is popular with the country as a whole, and enormously popular among Democrats, it is a much stronger argument to make voting against the deal a personal affront to the president. So it is entirely understandable that President Obama would want the public to have him believe that he sees the TPP as central to his legacy.

Thankfully, we have Politico and the mind readers on its staff who can tell us that President Obama is not acting as a politician but rather he actually believes this claim.

President Obama is working hard to push the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), going around the country promoting the pact. He must want Congress to approve it before he leaves office.

That much would be obvious to anyone. But Politico uses its incredible mind reading ability to go a step further. It tells us:

“Obama has been unwilling to abandon a deal that he regards as central to his legacy.”

The rest of us might be able to know that Obama says that he regards the TPP central to his legacy, but lacking Politico’s mind reading skills we wouldn’t know that he actually does regard the TPP as central to his legacy. Since President Obama is a politician, we know that he doesn’t always say exactly what he thinks, so we may not know whether or not he regards the TPP as central to his legacy.

We could believe that the is pushing the deal as a favor to the powerful business interests that helped to negotiate the deal, like the pharmaceutical industry, the entertainment industry, and the financial industry. These industries are expected to be major donors to Democratic campaigns this fall.

Of course, it would be difficult to get approval for the TPP based on the argument that it would benefit contributors to the Democratic Party. Since President Obama is popular with the country as a whole, and enormously popular among Democrats, it is a much stronger argument to make voting against the deal a personal affront to the president. So it is entirely understandable that President Obama would want the public to have him believe that he sees the TPP as central to his legacy.

Thankfully, we have Politico and the mind readers on its staff who can tell us that President Obama is not acting as a politician but rather he actually believes this claim.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Steve Pearlstein used a Washington Post column to correct an earlier scare story about robots taking all the jobs by fellow columnist David Ignatius. Pearlstein gets the story mostly right. If robots reduce the need for labor then someone will have additional money to spend. Either workers will get higher wages or prices of the goods produced by robots will fall, allowing people to buy more stuff. Most likely it will be some combination, but there is no basis for assuming that there will be no demand for workers. (This is true even if it goes to profits, since rich people will hire more help.)

There are two important qualifications to this argument. First, there is no evidence of massive displacement of workers by robots. This is exactly what productivity is about. Productivity is how much the economy produces for each hour of human (non-robot) labor. If robots were taking jobs in large numbers then productivity growth would be very rapid. In fact, productivity growth has been very slow. It actually has been negative in the last three quarters.

Of course this could change, maybe the robots are lurking just around the corner. But for now, just about all the economists I know are worried about the slow pace of productivity growth, not a huge surge in productivity displacing tens of millions of workers.

The other point that needs to be plastered across the top of Trump tower, is that when people benefit from “owning” technology it is because the government has chosen to subsidize their innovations. The issue here is patent protection, which is a main reason why the benefits of technology often are not widely shared. Patents give their owners monopolies over technology which allows them to charge prices that can be several thousand percent above the free market price.

There is an obvious rationale for patents — they give individuals and corporations an incentive to innovate. But in the last four decades we have implemented a variety of policies designed to make patent protection stronger and longer. As a result, more money is going to people who own patents. This money comes out of the pockets of the rest of us.

It is possible to argue that the strengthening of patents has been justified by its effect in promoting innovation (weak productivity growth suggests otherwise), but the fact this was a policy choice is not arguable. So when someone says that “technology” has caused inequality they are displaying their ignorance. Insofar as new technologies have been responsible for an upward redistribution of income, it has been the result of the political decision to provide these technologies with patent monopolies.

In other words, it is the folks in Congress and the White House who are responsible, not the robots.

Steve Pearlstein used a Washington Post column to correct an earlier scare story about robots taking all the jobs by fellow columnist David Ignatius. Pearlstein gets the story mostly right. If robots reduce the need for labor then someone will have additional money to spend. Either workers will get higher wages or prices of the goods produced by robots will fall, allowing people to buy more stuff. Most likely it will be some combination, but there is no basis for assuming that there will be no demand for workers. (This is true even if it goes to profits, since rich people will hire more help.)

There are two important qualifications to this argument. First, there is no evidence of massive displacement of workers by robots. This is exactly what productivity is about. Productivity is how much the economy produces for each hour of human (non-robot) labor. If robots were taking jobs in large numbers then productivity growth would be very rapid. In fact, productivity growth has been very slow. It actually has been negative in the last three quarters.

Of course this could change, maybe the robots are lurking just around the corner. But for now, just about all the economists I know are worried about the slow pace of productivity growth, not a huge surge in productivity displacing tens of millions of workers.

The other point that needs to be plastered across the top of Trump tower, is that when people benefit from “owning” technology it is because the government has chosen to subsidize their innovations. The issue here is patent protection, which is a main reason why the benefits of technology often are not widely shared. Patents give their owners monopolies over technology which allows them to charge prices that can be several thousand percent above the free market price.

There is an obvious rationale for patents — they give individuals and corporations an incentive to innovate. But in the last four decades we have implemented a variety of policies designed to make patent protection stronger and longer. As a result, more money is going to people who own patents. This money comes out of the pockets of the rest of us.

It is possible to argue that the strengthening of patents has been justified by its effect in promoting innovation (weak productivity growth suggests otherwise), but the fact this was a policy choice is not arguable. So when someone says that “technology” has caused inequality they are displaying their ignorance. Insofar as new technologies have been responsible for an upward redistribution of income, it has been the result of the political decision to provide these technologies with patent monopolies.

In other words, it is the folks in Congress and the White House who are responsible, not the robots.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT’s Dealbook section ran an interesting column on the “risks of unfettered capitalism” by St. John University Law Professor Jeff Sovern. The piece lists a number of abuses by corporations, including Volkswagen’s diesel scandal, Vioxx, and predatory lending. While Sovern is right in arguing for the need to rein in these abuses, it’s questionable whether this is an issue of “unfettered” capitalism.

In the case of Volkswagen, they deliberately lied to their customers about the product they were buying. Many of the people buying Volkswagen’s diesel cars were buying them explicitly because they wanted an environmentally friendly cars. It is not clear that it is accurate to call a system of capitalism “unfettered” if companies are allowed to lie to make money from their customers. Would this mean that in “unfettered” capitalism, airlines could charge people in advance for a plane ticket and then not actually give them a seat on the plane? That would be equating unfettered capitalism with legalized fraud.

In the case of Vioxx, Merck was alleged to have deliberately withheld evidence that the arthritis drug posed risks to patients with heart conditions. Its motivation was to increase sales. The reason that Merck had such a large incentive to increase sales was that the government gave them a patent monopoly that allowed it to sell Vioxx at a price that was several thousand percent above its free market price.

Without this patent monopoly, Merck’s profit margin on Vioxx would have been comparable to the margins that companies make selling paper cups and pencils. These sorts of profit margins would not likely have provided the sort of incentive to conceal evidence at the risk of patients’ health and life. It is hard to see how a government-granted patent monopoly can be seen as unfettered capitalism.

In the case of predatory lending, the question is whether companies can use deceptive practices to get people to take out loans if they do not fully understand the terms. The logic here is that smart people trained in law can write complicated contracts that a typical customer is not likely to be able to understand without spending a great deal of time and effort reviewing it.

If we allow for complex contracts with consumers to be enforceable, then we are providing an incentive for highly trained lawyers to spend a great deal of time figuring out how to design complex, deceptive contracts. We also then will effectively force consumers to spend far more time reviewing contracts to ensure that they are not being ripped off. This is an enormous waste of resources which is also likely to result in an upward redistribution of income.

As is the case here, in many instances where people claim they are talking about unfettered capitalism, they are actually talking about one person’s “right” to dump their sewage on their neighbor’s lawn. The dumper is invariably more powerful than the dumpee. It gives the issue way more respect than it deserves to ascribe to it a principle like “unfettered capitalism.” It’s really just a question of whether we want a system where the rich are allowed to rip off everyone else.

The NYT’s Dealbook section ran an interesting column on the “risks of unfettered capitalism” by St. John University Law Professor Jeff Sovern. The piece lists a number of abuses by corporations, including Volkswagen’s diesel scandal, Vioxx, and predatory lending. While Sovern is right in arguing for the need to rein in these abuses, it’s questionable whether this is an issue of “unfettered” capitalism.

In the case of Volkswagen, they deliberately lied to their customers about the product they were buying. Many of the people buying Volkswagen’s diesel cars were buying them explicitly because they wanted an environmentally friendly cars. It is not clear that it is accurate to call a system of capitalism “unfettered” if companies are allowed to lie to make money from their customers. Would this mean that in “unfettered” capitalism, airlines could charge people in advance for a plane ticket and then not actually give them a seat on the plane? That would be equating unfettered capitalism with legalized fraud.

In the case of Vioxx, Merck was alleged to have deliberately withheld evidence that the arthritis drug posed risks to patients with heart conditions. Its motivation was to increase sales. The reason that Merck had such a large incentive to increase sales was that the government gave them a patent monopoly that allowed it to sell Vioxx at a price that was several thousand percent above its free market price.

Without this patent monopoly, Merck’s profit margin on Vioxx would have been comparable to the margins that companies make selling paper cups and pencils. These sorts of profit margins would not likely have provided the sort of incentive to conceal evidence at the risk of patients’ health and life. It is hard to see how a government-granted patent monopoly can be seen as unfettered capitalism.

In the case of predatory lending, the question is whether companies can use deceptive practices to get people to take out loans if they do not fully understand the terms. The logic here is that smart people trained in law can write complicated contracts that a typical customer is not likely to be able to understand without spending a great deal of time and effort reviewing it.

If we allow for complex contracts with consumers to be enforceable, then we are providing an incentive for highly trained lawyers to spend a great deal of time figuring out how to design complex, deceptive contracts. We also then will effectively force consumers to spend far more time reviewing contracts to ensure that they are not being ripped off. This is an enormous waste of resources which is also likely to result in an upward redistribution of income.

As is the case here, in many instances where people claim they are talking about unfettered capitalism, they are actually talking about one person’s “right” to dump their sewage on their neighbor’s lawn. The dumper is invariably more powerful than the dumpee. It gives the issue way more respect than it deserves to ascribe to it a principle like “unfettered capitalism.” It’s really just a question of whether we want a system where the rich are allowed to rip off everyone else.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

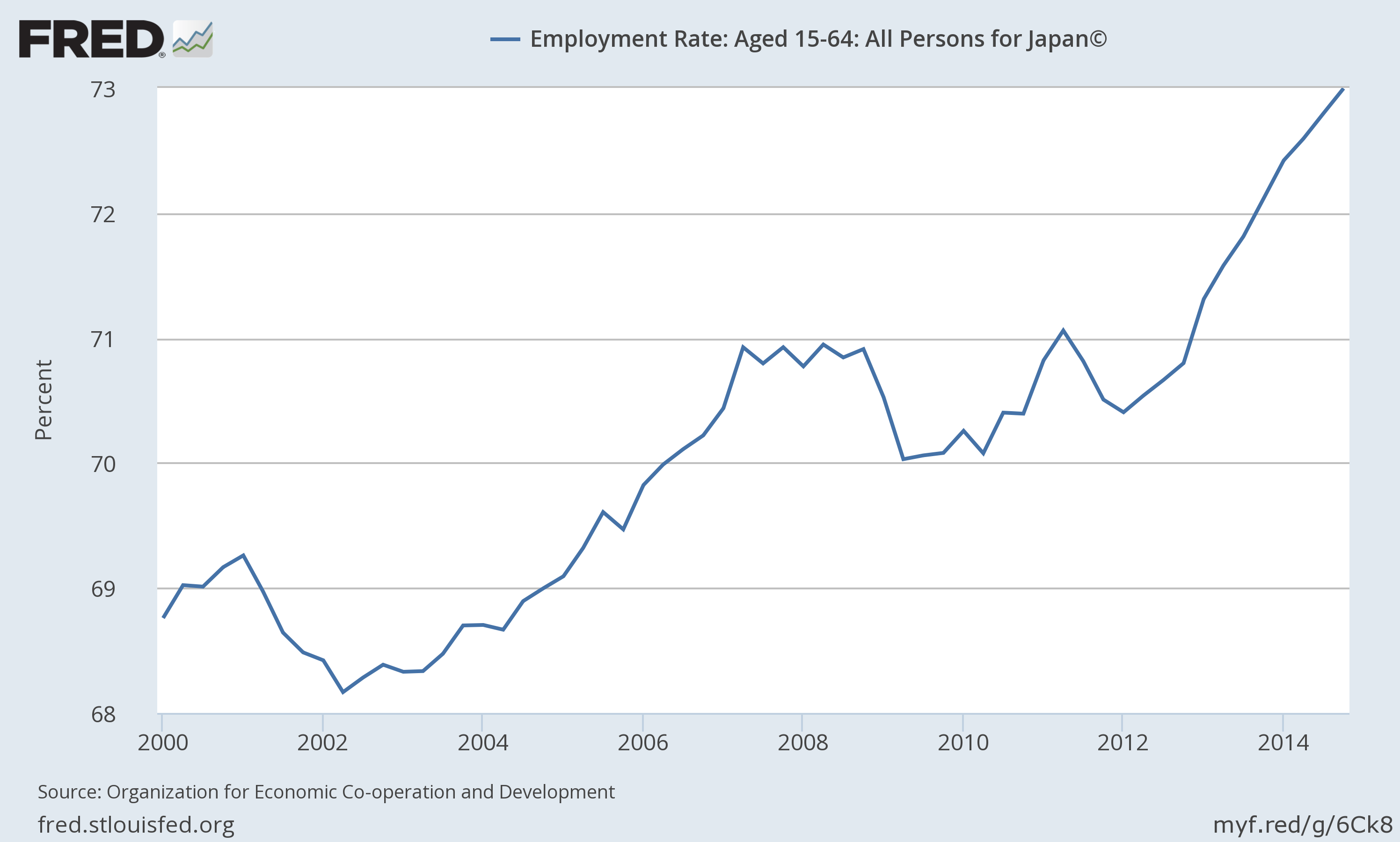

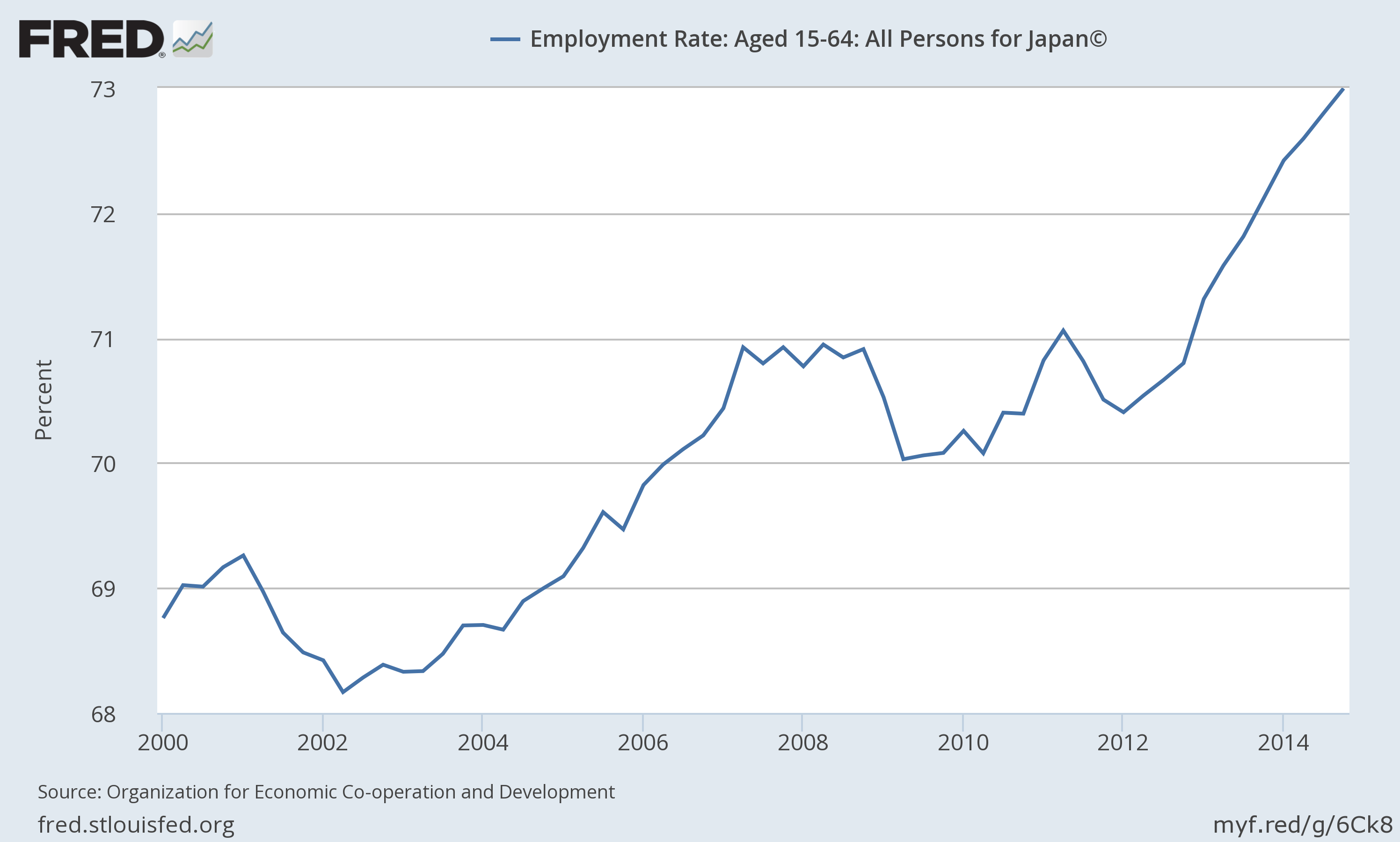

This short piece on Japan’s GDP growth reminded me that I wanted to post a graph showing the rise in Japan’s employment rate under Abe. Here’s the basic picture showing the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) for people between the ages of 16 and 64 since 2000.

As can seen, Japan’s EPOP fell following the 2001 recession. It had made up lost ground by 2005 and continued to rise until 2007. It stagnated for roughly two years and then rose somewhat before starting to drop again in 2011. It was falling when Abe took over in December of 2012.

Since then the EPOP has risen by 2.5 percentage points. This is a huge gain that would be equivalent to another 6.2 million jobs in the United States. Japan’s growth has certainly not be inspiring under Abe, but this increase in employment is quite impressive. By this measure, Abenomics has been very successful.

This short piece on Japan’s GDP growth reminded me that I wanted to post a graph showing the rise in Japan’s employment rate under Abe. Here’s the basic picture showing the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) for people between the ages of 16 and 64 since 2000.

As can seen, Japan’s EPOP fell following the 2001 recession. It had made up lost ground by 2005 and continued to rise until 2007. It stagnated for roughly two years and then rose somewhat before starting to drop again in 2011. It was falling when Abe took over in December of 2012.

Since then the EPOP has risen by 2.5 percentage points. This is a huge gain that would be equivalent to another 6.2 million jobs in the United States. Japan’s growth has certainly not be inspiring under Abe, but this increase in employment is quite impressive. By this measure, Abenomics has been very successful.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión