He uses his column today to tell us that “this century is broken.” Much of his tale involves the old problem with men story.

“For every one American man aged 25 to 55 looking for work, there are three who have dropped out of the labor force. If Americans were working at the same rates they were when this century started, over 10 million more people would have jobs. As Eberstadt puts it, ‘The plain fact is that 21st-century America has witnessed a dreadful collapse of work.’

“That means there’s an army of Americans semi-attached to their communities, who struggle to contribute, to realize their capacities and find their dignity. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics time-use studies, these labor force dropouts spend on average 2,000 hours a year watching some screen. That’s about the number of hours that usually go to a full-time job.”

While it apparently makes folks like Brooks feel good to tell these sorts of morality tales about the failings of men today, it actually has nothing to do with reality. While fewer prime-age men (ages 25–54) men are working today than in 2000, the share of prime-age women has fallen by almost the same amount. Furthermore, the percent of prime-age women working had been rising prior to 2000 and was projected to continue to rise by most economists.

The fact that women’s employment rates have fallen as well is important because it indicates that, contrary to what Brooks tells us, the problem is not a gender specific moral failing. The problem is most likely a good old-fashioned shortfall in demand in the economy.

This matters a great deal because we actually do know how to create more demand. It’s called “spending money.” This means that if the government spent more money on things like education, health care, and infrastructure, we could get more of these prime-age men and women employed. There are other ways to create demand. For example, if we got our trade deficit down by reducing the value of the dollar it would also generate more demand and employment.

If we are troubled by the large number of prime-age workers who are not employed there are policies that we could pursue that would address the problem. In other words, we should be more worried about the moral failings of people in a position to make economic policy than the moral failings of the folks not working.

He uses his column today to tell us that “this century is broken.” Much of his tale involves the old problem with men story.

“For every one American man aged 25 to 55 looking for work, there are three who have dropped out of the labor force. If Americans were working at the same rates they were when this century started, over 10 million more people would have jobs. As Eberstadt puts it, ‘The plain fact is that 21st-century America has witnessed a dreadful collapse of work.’

“That means there’s an army of Americans semi-attached to their communities, who struggle to contribute, to realize their capacities and find their dignity. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics time-use studies, these labor force dropouts spend on average 2,000 hours a year watching some screen. That’s about the number of hours that usually go to a full-time job.”

While it apparently makes folks like Brooks feel good to tell these sorts of morality tales about the failings of men today, it actually has nothing to do with reality. While fewer prime-age men (ages 25–54) men are working today than in 2000, the share of prime-age women has fallen by almost the same amount. Furthermore, the percent of prime-age women working had been rising prior to 2000 and was projected to continue to rise by most economists.

The fact that women’s employment rates have fallen as well is important because it indicates that, contrary to what Brooks tells us, the problem is not a gender specific moral failing. The problem is most likely a good old-fashioned shortfall in demand in the economy.

This matters a great deal because we actually do know how to create more demand. It’s called “spending money.” This means that if the government spent more money on things like education, health care, and infrastructure, we could get more of these prime-age men and women employed. There are other ways to create demand. For example, if we got our trade deficit down by reducing the value of the dollar it would also generate more demand and employment.

If we are troubled by the large number of prime-age workers who are not employed there are policies that we could pursue that would address the problem. In other words, we should be more worried about the moral failings of people in a position to make economic policy than the moral failings of the folks not working.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

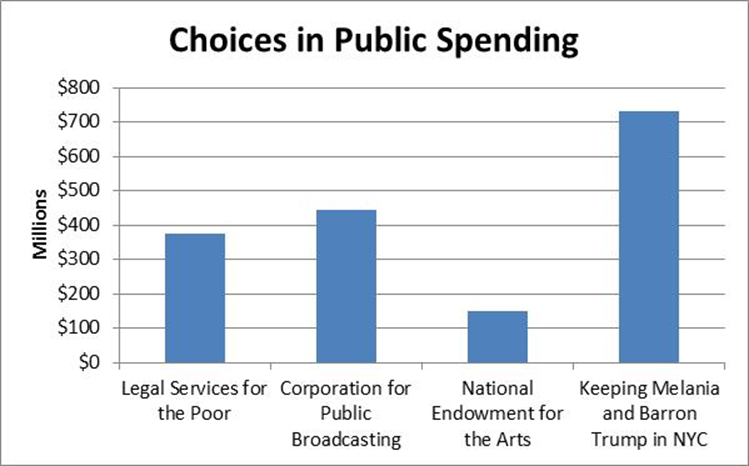

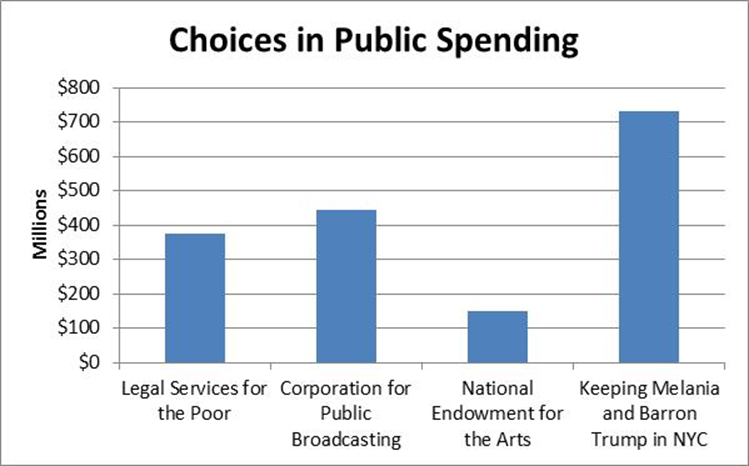

We all know about the need to make trade-offs in budgeting, most of us have to do it on a regular basis in our daily lives. But what about the trade-offs for the federal government? Arguably there is no need for trade-offs right now. Both interest rates and inflation are at low levels, so it is not obvious that there is any problem with larger deficits, but folks in both parties are fixated on the need to run low budget deficits or even to have balanced budgets, so these politics dictate the need for trade-offs.

In this context, it is worth making some comparisons as the Republicans seem prepared to slash a number of relatively low cost programs that have received considerable visibility. At the top of this list would be federal funding for Legal Services, a program that has provided legal assistance to low income people for decades. This program provides lawyers for people facing foreclosures or evictions, for people who need help with a divorce or will, or for many other situations that would typically require the assistance of a lawyer. The appropriation last year came to $375 million, or 0.011 percent of the federal budget.

Another item on the chopping block is the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). CPB helps fund National Public Radio as well as public television stations around the country. It got $445 million from the federal government last year or 0.013 percent of total spending.

Then there is the National Endowment of the Arts (NEA). The NEA supports a variety of education and cultural events around the country. It got just under $150 million last year or 0.004 percent of the total budget. There are a number of other small programs also on the chopping block, including AmeriCorps and the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy.

It is interesting to compare the spending of these programs that face cuts or may be eliminated altogether with spending of security for President Trump and his family. In the past, presidents have generally tried to limit their own travel and that of their families so as not to create large security bills for the country. Apparently, this is not a concern of President Trump.

Unlike past presidents, he has requested Secret Service protection for his adult children. Given their travel habits running President Trump’s business, this is likely to be a considerable expense for the government. For example, the Washington Post reported that one trip to Uruguay by Eric Trump to open a hotel there cost the government almost $100,000 in security expenses. In addition, Trump’s decision to take his weekends at his golf club in Florida, rather the White House or Camp David, costs us more than $3 million a shot. And the decision by Melania Trump to stay in New York with her son is apparently costing taxpayers close to $2 million a day.

People may want to ask where they get the most money for their tax dollars.

We all know about the need to make trade-offs in budgeting, most of us have to do it on a regular basis in our daily lives. But what about the trade-offs for the federal government? Arguably there is no need for trade-offs right now. Both interest rates and inflation are at low levels, so it is not obvious that there is any problem with larger deficits, but folks in both parties are fixated on the need to run low budget deficits or even to have balanced budgets, so these politics dictate the need for trade-offs.

In this context, it is worth making some comparisons as the Republicans seem prepared to slash a number of relatively low cost programs that have received considerable visibility. At the top of this list would be federal funding for Legal Services, a program that has provided legal assistance to low income people for decades. This program provides lawyers for people facing foreclosures or evictions, for people who need help with a divorce or will, or for many other situations that would typically require the assistance of a lawyer. The appropriation last year came to $375 million, or 0.011 percent of the federal budget.

Another item on the chopping block is the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). CPB helps fund National Public Radio as well as public television stations around the country. It got $445 million from the federal government last year or 0.013 percent of total spending.

Then there is the National Endowment of the Arts (NEA). The NEA supports a variety of education and cultural events around the country. It got just under $150 million last year or 0.004 percent of the total budget. There are a number of other small programs also on the chopping block, including AmeriCorps and the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy.

It is interesting to compare the spending of these programs that face cuts or may be eliminated altogether with spending of security for President Trump and his family. In the past, presidents have generally tried to limit their own travel and that of their families so as not to create large security bills for the country. Apparently, this is not a concern of President Trump.

Unlike past presidents, he has requested Secret Service protection for his adult children. Given their travel habits running President Trump’s business, this is likely to be a considerable expense for the government. For example, the Washington Post reported that one trip to Uruguay by Eric Trump to open a hotel there cost the government almost $100,000 in security expenses. In addition, Trump’s decision to take his weekends at his golf club in Florida, rather the White House or Camp David, costs us more than $3 million a shot. And the decision by Melania Trump to stay in New York with her son is apparently costing taxpayers close to $2 million a day.

People may want to ask where they get the most money for their tax dollars.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post warned readers that health care costs were about to start rising sharply again in an article reporting new projections from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service (CMS). While there is definitely a risk that these projections may be right, and health care will impose a considerably larger burden on the economy over the next decade than it does now, it is worth noting that the projections from CMS have not proven especially accurate in the past.

For example, in 2007 it projected that health care spending would rise as a share of GDP from 16.3 percent in 2007 to 18.8 percent in 2015, the most recent year for which data are available. According to CMS, spending in 2015 was just 17.8 percent of GDP, a full percentage point less than had been projected.

It is also worth noting that we pay roughly twice as much for physicians, drugs, and other items used in providing health care than other wealthy countries. If we become less protectionist over the next decade then we might expect prices in the United States to fall towards world levels, which would dampen the pace of health care cost growth.

The Washington Post warned readers that health care costs were about to start rising sharply again in an article reporting new projections from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service (CMS). While there is definitely a risk that these projections may be right, and health care will impose a considerably larger burden on the economy over the next decade than it does now, it is worth noting that the projections from CMS have not proven especially accurate in the past.

For example, in 2007 it projected that health care spending would rise as a share of GDP from 16.3 percent in 2007 to 18.8 percent in 2015, the most recent year for which data are available. According to CMS, spending in 2015 was just 17.8 percent of GDP, a full percentage point less than had been projected.

It is also worth noting that we pay roughly twice as much for physicians, drugs, and other items used in providing health care than other wealthy countries. If we become less protectionist over the next decade then we might expect prices in the United States to fall towards world levels, which would dampen the pace of health care cost growth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Hey, no one said Speaker Ryan wasn’t a smart guy. (Actually, many people have, but whatever.) Anyhow, the Republicans have published an outline of their proposal for an Obamacare replacement. It seems designed to ensure that tens of millions of people lose their health insurance coverage.

The basic story is that the plan is designed to fragment the market by both allowing a wider range of insurance policies and also by promoting health savings accounts in which people can place money tax free. (Oh yes, and the financial industry can make lots of money on fees.) This will mean that almost anyone in good health will get catastrophic policies that cover large expenses, but leave most normal expenses to the patient. Since most people are relatively healthy, this would be a good deal for most of the population.

The numbers on this are striking. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services projects that health care costs in 2017 will average $10,800 this year. The average for cost for the ten percent of most expensive patients is $54,000. The average cost for the least expensive 50 percent is just $700. (These figures include seniors who are covered by Medicare. The skewing would be a bit less if the over 65 age group were pulled out of the calculation.)

Since most people have very little by way of health care spending, it would make sense for them to use the tax credit proposed in the Republican plan to buy a catastrophic plan, that may have a deductible of $10,000 or $12,000 or more. This plan would cost little and allow them to put most of the credit in a health savings account.

This means that the only people who would be interested in buying conventional insurance policies would be people with high medical expenses. Insurers will price these policies to reflect the anticipated costs. This means that they would have to cost tens of thousands of dollars per person. Most of these people will not be able to afford these plans. The credit proposed by the Republicans (which is likely to be around $2,500 from the description in the plan), will not go far towards meeting the cost of policies for these people.

So, the Republicans deserve credit for devising a plan to reduce the cost of insurance for healthy people. It just means that tens of millions of people who actually need insurance won’t be able to get it.

Hey, no one said Speaker Ryan wasn’t a smart guy. (Actually, many people have, but whatever.) Anyhow, the Republicans have published an outline of their proposal for an Obamacare replacement. It seems designed to ensure that tens of millions of people lose their health insurance coverage.

The basic story is that the plan is designed to fragment the market by both allowing a wider range of insurance policies and also by promoting health savings accounts in which people can place money tax free. (Oh yes, and the financial industry can make lots of money on fees.) This will mean that almost anyone in good health will get catastrophic policies that cover large expenses, but leave most normal expenses to the patient. Since most people are relatively healthy, this would be a good deal for most of the population.

The numbers on this are striking. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services projects that health care costs in 2017 will average $10,800 this year. The average for cost for the ten percent of most expensive patients is $54,000. The average cost for the least expensive 50 percent is just $700. (These figures include seniors who are covered by Medicare. The skewing would be a bit less if the over 65 age group were pulled out of the calculation.)

Since most people have very little by way of health care spending, it would make sense for them to use the tax credit proposed in the Republican plan to buy a catastrophic plan, that may have a deductible of $10,000 or $12,000 or more. This plan would cost little and allow them to put most of the credit in a health savings account.

This means that the only people who would be interested in buying conventional insurance policies would be people with high medical expenses. Insurers will price these policies to reflect the anticipated costs. This means that they would have to cost tens of thousands of dollars per person. Most of these people will not be able to afford these plans. The credit proposed by the Republicans (which is likely to be around $2,500 from the description in the plan), will not go far towards meeting the cost of policies for these people.

So, the Republicans deserve credit for devising a plan to reduce the cost of insurance for healthy people. It just means that tens of millions of people who actually need insurance won’t be able to get it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Of course China could argue this, it would be really stupid, but nothing prohibits countries from making stupid arguments if they want to push their agenda. In this vein, the Wall Street Journal told readers that if the U.S. took actions against China and other countries for deliberately depressing the value of their currencies by buying dollars they:

“…could argue that Federal Reserve policies that weaken the dollar qualify as subsidies.”

Obviously they could make this argument, but it makes little sense. There is a clear difference between central bank policies designed to affect the domestic economy and policies that are designed first and foremost to affect the value of the currency. It really is not hard for people to understand the distinction between a central bank buying its own country’s bonds and a central bank buying the bonds and assets of other countries. This is about as sharp and clear a distinction as imaginable.

Central bank policy will affect will the value of the currency, but so will other policies. For example, a large reduction in government spending would be expected to reduce output and lower interest rates. Other countries could with equally good grounds contest this cut in government spending as an unfair subsidy.

This is a clear case where the Wall Street Journal does not like a policy and is inventing reasons for its readers to go along with its view.

Of course China could argue this, it would be really stupid, but nothing prohibits countries from making stupid arguments if they want to push their agenda. In this vein, the Wall Street Journal told readers that if the U.S. took actions against China and other countries for deliberately depressing the value of their currencies by buying dollars they:

“…could argue that Federal Reserve policies that weaken the dollar qualify as subsidies.”

Obviously they could make this argument, but it makes little sense. There is a clear difference between central bank policies designed to affect the domestic economy and policies that are designed first and foremost to affect the value of the currency. It really is not hard for people to understand the distinction between a central bank buying its own country’s bonds and a central bank buying the bonds and assets of other countries. This is about as sharp and clear a distinction as imaginable.

Central bank policy will affect will the value of the currency, but so will other policies. For example, a large reduction in government spending would be expected to reduce output and lower interest rates. Other countries could with equally good grounds contest this cut in government spending as an unfair subsidy.

This is a clear case where the Wall Street Journal does not like a policy and is inventing reasons for its readers to go along with its view.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Donald Trump has used his podium on several occasions to harangue companies about moving jobs overseas. This is probably not an effective way to conduct economic policy, but Justin Wolfers misled NYT readers in claiming:

“Research shows that efforts to boost employment by making it difficult or costly to fire workers have backfired. The prospect of a costly and lengthy legal battle for laid-off employees makes it less appealing to hire new workers. The result has been that higher firing costs have led to to weaker productivity, sclerotic labor markets and higher unemployment.”

Actually, more recent research results, including more recent work from the OECD (the source to which he links), show that there is no necessary link between restrictions on firing and unemployment. While excessive restrictions on firing can undoubtedly hurt employment and growth, there is no reason to assume that moderate amounts of severance pay, or other disincentives to dismiss workers, will discourage investment and hiring.

A requirement to give longer term workers severance pay when dismissed does change the incentives facing an employer. In this situation they have more incentive to retrain workers to ensure that they are as productive as possible. They may also opt to invest more in existing facilities rather than move overseas in order to avoid severance pay.

Donald Trump has used his podium on several occasions to harangue companies about moving jobs overseas. This is probably not an effective way to conduct economic policy, but Justin Wolfers misled NYT readers in claiming:

“Research shows that efforts to boost employment by making it difficult or costly to fire workers have backfired. The prospect of a costly and lengthy legal battle for laid-off employees makes it less appealing to hire new workers. The result has been that higher firing costs have led to to weaker productivity, sclerotic labor markets and higher unemployment.”

Actually, more recent research results, including more recent work from the OECD (the source to which he links), show that there is no necessary link between restrictions on firing and unemployment. While excessive restrictions on firing can undoubtedly hurt employment and growth, there is no reason to assume that moderate amounts of severance pay, or other disincentives to dismiss workers, will discourage investment and hiring.

A requirement to give longer term workers severance pay when dismissed does change the incentives facing an employer. In this situation they have more incentive to retrain workers to ensure that they are as productive as possible. They may also opt to invest more in existing facilities rather than move overseas in order to avoid severance pay.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión