Back in the 1990s, whining about the impending disaster from the retirement of baby boomer cohorts was all the rage. Private equity billionaire Peter Peterson’s polemics were big sellers, as very serious people struggled with how we could deal with this tidal wave of retirees. The basic story was that a rising ratio of retirees to workers would create a crushing burden for the younger people that were still in the labor force.

This argument went somewhat out of style over time. In part, the projection of exploding healthcare costs that drove the horror story turned out not to happen. Back in 2000, the long-term projections showed that healthcare would account for roughly one-third of total consumption spending by now. In fact, actual healthcare spending is less than 25.0 percent of total consumption. The difference between the 2000 projection and actual healthcare spending leaves about $1.5 trillion on the table (around $12k per family, each year) for us to spend on other things.

The second reason this demographic horror story went out of style was the slow recovery from the Great Recession. It took us over a decade to return to full employment following the collapse of the housing bubble. The problem for the economy in this decade was not that spending was too high, but rather that it was too low. (This is known as the “which way is up?” problem in economics.) If we had larger deficits during the last decade it would have provided a boost to growth and led to less unemployment.

Finally, the impending retirement of the baby boomers was no longer impending as they began to retire in the last decade. At the start of the decade the oldest baby boomers were already age 64. By 2020, the oldest baby boomers were age 74 and the youngest were already age 56. A substantial portion of the baby boom generation was already retired and the world had not ended.

The Return of the Demographic Crisis

But, as they say in Washington, no bad idea ever stays dead for long. In recent months the demographic crisis from retiring baby boomers seems to be everywhere. The major news outlets are filled with piece after piece telling us that we are running out of workers, at least when they are not telling us how the spread of robots and AI will create mass unemployment. (Yes, those claims are contradictory, but don’t tell any elite intellectual type.)

Anyhow, the basic story of the aging crisis is that workers will have to turn over a large portion of their paycheck to cover the costs of a growing population of retirees. This concern is supposed to lead us to cut Social Security and Medicare benefits and tell workers that they have to work later in life.

There are a couple of important points to be made at the start of any serious discussion. First, we have already raised the age at which people are eligible for full Social Security benefits. It had been 65 for people born before 1940. It has been gradually raised to 67 for people born after 1960. So, we have already taken account of people’s increased longevity in setting the parameters for Social Security.

The second point is that the gains in life expectancy have not been evenly shared. For people born in 1930 the gap in life expectancy, at age 50, between the top income quintile and the bottom income quintile for men was 5.0 years, and for women was 3.9 years. For the cohort born in 1960, the gap had increased to 12.7 years for men and 13.6 years for women. This means that almost all the gains in life expectancy over the last half century have been for those at the top of the income ladder. Those further down have seen little or no gains in life expectancy.

Next, it is important to have some idea of the dimensions of the aging “crisis.” We all know about the widely touted projected shortfalls in Social Security and Medicare. Let’s imagine that we made them up by raising the payroll tax. (That’s not the best way to deal with the problem, but this is just a hypothetical exercise.)

Suppose we raised the payroll tax by 4.0 percentage points tomorrow. Given current projections, this would be roughly enough to make the Social Security and Medicare trust funds solvent forever.

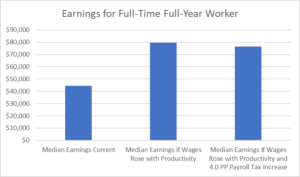

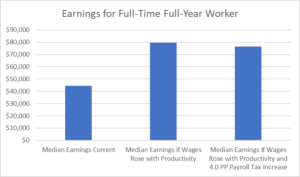

The graph below shows the current annual wage for a person getting the median wage, working full-time full year (50 weeks at 40 hours a week). It also shows what this worker would be getting if the median wage had kept pace with productivity growth, as it did in the long post-war boom from 1947 to 1973. And, it shows what this pay would have been if, in this scenario, we increased the payroll tax by 4.0 percentage points.[1]

Source: Economic Policy Institute, BEA, BLS, and author’s calculations.

Given the current median wage of just over $24 an hour, the full-year pay, net of payroll taxes (7.65 percent on the worker’s side) would be just under $46,600. By contrast, if their pay had kept pace with productivity growth over the last half-century, it would be over $79,700 net of payroll taxes.

If we said that it was necessary to raise the payroll tax by 4.0 percentage points (half on the employer and half on the employee) to deal with the cost of supporting an aging population, then the annual wage would fall to $76,500.[2] That would still be more than 70 percent above its current level.

The reality is that most workers stand to lose an order of magnitude more income due to upward redistribution than what they could conceivably risk from the changing demographics of the country. If we think that an aging population poses a risk to the living standards of younger workers, then upward redistribution is a disaster.

The Causes of Inequality

The hawkers of the demographic crisis story seem to want us to believe that inequality just happened and we just have to live with it. Of course, that is a lie. Inequality was the result of deliberate policy choices. We could have pursued different policies that would have not led to the rise in inequality we have seen over the last half century.

My book, Rigged, goes through the story in more detail, but I will quickly outline the basic picture. First, we have redistributed a massive amount of income upward with longer and stronger patent and copyright monopolies and related protections. Bill Gates would likely still be working for a living (actually, he could be collecting Social Security) if the government didn’t threaten to imprison people who made copies of Microsoft software without his permission.

It is common for economists to claim that technology was a major factor in upward redistribution. That is not true, it was our rules on technology that drove the upward redistribution. There are other, arguably more efficient, mechanisms for supporting innovation and creative work. These would likely not lead to as much inequality.

We also have pursued a narrow path of globalization where we quite deliberately put our manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world. This had the predicted and actual effect of lowering the wages of manufacturing workers and non-college-educated workers more generally.

At the same time, we maintained or even increased the protections for highly educated professionals, like doctors and dentists. As a result, our doctors earn twice as much as doctors in other wealthy countries.

If we didn’t want to increase inequality, we could have pursued a course of globalization that focused foremost on reducing the barriers that protected our most highly paid workers. But these professionals, unlike manufacturing workers, have enough political power to ensure that trade deals will not be structured in ways that threaten their livelihood.

Our financial sector is a cesspool of waste and corruption. An efficient financial sector is a small financial sector. Instead of pursuing policies to promote efficiency, we have pursued policies that have encouraged bloat in this sector, which is the source of many of the biggest fortunes in the country.

When the market would have massively downsized the financial industry in the financial crisis, leaders of both political parties could not move quickly enough to rush to its rescue. There were no market fundamentalists when the great fortunes in the industry were in jeopardy.

We have also structured rules on corporate governance in ways that allow CEOs to rip off the companies they work for. The corporate directors, who are ostensibly charged with making sure CEOs and top management aren’t overpaid, for the most part, don’t even see this as part of their job description.

The bloated pay for CEOs warps the pay structure more generally. When a CEO can get $30 million and third-tier execs can get $2-$3 million, it creates a situation where even heads of charities and universities can command multi-million dollar paychecks.

High unemployment has also been a tool for lowering the pay of the typical worker. The only times where the pay of the median worker has outpaced inflation in the last half century have been when the unemployment rate was close to or below 4.0 percent.

The fact that anti-trust policy has been little used in the last four decades has likely also played a role in the recent shift from wages to profits. It will be interesting to see if the more aggressive policies pursued by the Biden administration have any effect in this area.

In short, we have made a series of policy decisions that have led to a massive upward redistribution of income in the last half-century. The impact of this upward redistribution on the income of young workers dwarfs the impact of demographics. Unfortunately, our news outlets seem more interested in highlighting the demographic issue than the causes of inequality.

There is one final point. We absolutely should be spending more money on daycare, healthcare for pregnant women and young children, early childhood education, and a variety of other areas that would benefit the young. However, there is no reason to believe that spending on the elderly is the obstacle preventing more spending in these areas.

[1] The median wage is taken from the Economic Policy Institute’s State of Working America data library. The 2022 was adjusted for the increase in the personal consumption expenditure deflator from 2022 to September of 2023 to get current dollars. Productivity growth since 1973 was adjusted for differences in deflators and the distinction between net and gross income, as well as the declining wage share of compensation to get the 2023 wage figure.

[2] Much of the projected shortfall in Social Security is a direct result of the upward redistribution of income since a larger share of wage income falls over the cap on taxable wage income (currently $186,600), as well as the shift from wages to profits in the last two decades.

Back in the 1990s, whining about the impending disaster from the retirement of baby boomer cohorts was all the rage. Private equity billionaire Peter Peterson’s polemics were big sellers, as very serious people struggled with how we could deal with this tidal wave of retirees. The basic story was that a rising ratio of retirees to workers would create a crushing burden for the younger people that were still in the labor force.

This argument went somewhat out of style over time. In part, the projection of exploding healthcare costs that drove the horror story turned out not to happen. Back in 2000, the long-term projections showed that healthcare would account for roughly one-third of total consumption spending by now. In fact, actual healthcare spending is less than 25.0 percent of total consumption. The difference between the 2000 projection and actual healthcare spending leaves about $1.5 trillion on the table (around $12k per family, each year) for us to spend on other things.

The second reason this demographic horror story went out of style was the slow recovery from the Great Recession. It took us over a decade to return to full employment following the collapse of the housing bubble. The problem for the economy in this decade was not that spending was too high, but rather that it was too low. (This is known as the “which way is up?” problem in economics.) If we had larger deficits during the last decade it would have provided a boost to growth and led to less unemployment.

Finally, the impending retirement of the baby boomers was no longer impending as they began to retire in the last decade. At the start of the decade the oldest baby boomers were already age 64. By 2020, the oldest baby boomers were age 74 and the youngest were already age 56. A substantial portion of the baby boom generation was already retired and the world had not ended.

The Return of the Demographic Crisis

But, as they say in Washington, no bad idea ever stays dead for long. In recent months the demographic crisis from retiring baby boomers seems to be everywhere. The major news outlets are filled with piece after piece telling us that we are running out of workers, at least when they are not telling us how the spread of robots and AI will create mass unemployment. (Yes, those claims are contradictory, but don’t tell any elite intellectual type.)

Anyhow, the basic story of the aging crisis is that workers will have to turn over a large portion of their paycheck to cover the costs of a growing population of retirees. This concern is supposed to lead us to cut Social Security and Medicare benefits and tell workers that they have to work later in life.

There are a couple of important points to be made at the start of any serious discussion. First, we have already raised the age at which people are eligible for full Social Security benefits. It had been 65 for people born before 1940. It has been gradually raised to 67 for people born after 1960. So, we have already taken account of people’s increased longevity in setting the parameters for Social Security.

The second point is that the gains in life expectancy have not been evenly shared. For people born in 1930 the gap in life expectancy, at age 50, between the top income quintile and the bottom income quintile for men was 5.0 years, and for women was 3.9 years. For the cohort born in 1960, the gap had increased to 12.7 years for men and 13.6 years for women. This means that almost all the gains in life expectancy over the last half century have been for those at the top of the income ladder. Those further down have seen little or no gains in life expectancy.

Next, it is important to have some idea of the dimensions of the aging “crisis.” We all know about the widely touted projected shortfalls in Social Security and Medicare. Let’s imagine that we made them up by raising the payroll tax. (That’s not the best way to deal with the problem, but this is just a hypothetical exercise.)

Suppose we raised the payroll tax by 4.0 percentage points tomorrow. Given current projections, this would be roughly enough to make the Social Security and Medicare trust funds solvent forever.

The graph below shows the current annual wage for a person getting the median wage, working full-time full year (50 weeks at 40 hours a week). It also shows what this worker would be getting if the median wage had kept pace with productivity growth, as it did in the long post-war boom from 1947 to 1973. And, it shows what this pay would have been if, in this scenario, we increased the payroll tax by 4.0 percentage points.[1]

Source: Economic Policy Institute, BEA, BLS, and author’s calculations.

Given the current median wage of just over $24 an hour, the full-year pay, net of payroll taxes (7.65 percent on the worker’s side) would be just under $46,600. By contrast, if their pay had kept pace with productivity growth over the last half-century, it would be over $79,700 net of payroll taxes.

If we said that it was necessary to raise the payroll tax by 4.0 percentage points (half on the employer and half on the employee) to deal with the cost of supporting an aging population, then the annual wage would fall to $76,500.[2] That would still be more than 70 percent above its current level.

The reality is that most workers stand to lose an order of magnitude more income due to upward redistribution than what they could conceivably risk from the changing demographics of the country. If we think that an aging population poses a risk to the living standards of younger workers, then upward redistribution is a disaster.

The Causes of Inequality

The hawkers of the demographic crisis story seem to want us to believe that inequality just happened and we just have to live with it. Of course, that is a lie. Inequality was the result of deliberate policy choices. We could have pursued different policies that would have not led to the rise in inequality we have seen over the last half century.

My book, Rigged, goes through the story in more detail, but I will quickly outline the basic picture. First, we have redistributed a massive amount of income upward with longer and stronger patent and copyright monopolies and related protections. Bill Gates would likely still be working for a living (actually, he could be collecting Social Security) if the government didn’t threaten to imprison people who made copies of Microsoft software without his permission.

It is common for economists to claim that technology was a major factor in upward redistribution. That is not true, it was our rules on technology that drove the upward redistribution. There are other, arguably more efficient, mechanisms for supporting innovation and creative work. These would likely not lead to as much inequality.

We also have pursued a narrow path of globalization where we quite deliberately put our manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world. This had the predicted and actual effect of lowering the wages of manufacturing workers and non-college-educated workers more generally.

At the same time, we maintained or even increased the protections for highly educated professionals, like doctors and dentists. As a result, our doctors earn twice as much as doctors in other wealthy countries.

If we didn’t want to increase inequality, we could have pursued a course of globalization that focused foremost on reducing the barriers that protected our most highly paid workers. But these professionals, unlike manufacturing workers, have enough political power to ensure that trade deals will not be structured in ways that threaten their livelihood.

Our financial sector is a cesspool of waste and corruption. An efficient financial sector is a small financial sector. Instead of pursuing policies to promote efficiency, we have pursued policies that have encouraged bloat in this sector, which is the source of many of the biggest fortunes in the country.

When the market would have massively downsized the financial industry in the financial crisis, leaders of both political parties could not move quickly enough to rush to its rescue. There were no market fundamentalists when the great fortunes in the industry were in jeopardy.

We have also structured rules on corporate governance in ways that allow CEOs to rip off the companies they work for. The corporate directors, who are ostensibly charged with making sure CEOs and top management aren’t overpaid, for the most part, don’t even see this as part of their job description.

The bloated pay for CEOs warps the pay structure more generally. When a CEO can get $30 million and third-tier execs can get $2-$3 million, it creates a situation where even heads of charities and universities can command multi-million dollar paychecks.

High unemployment has also been a tool for lowering the pay of the typical worker. The only times where the pay of the median worker has outpaced inflation in the last half century have been when the unemployment rate was close to or below 4.0 percent.

The fact that anti-trust policy has been little used in the last four decades has likely also played a role in the recent shift from wages to profits. It will be interesting to see if the more aggressive policies pursued by the Biden administration have any effect in this area.

In short, we have made a series of policy decisions that have led to a massive upward redistribution of income in the last half-century. The impact of this upward redistribution on the income of young workers dwarfs the impact of demographics. Unfortunately, our news outlets seem more interested in highlighting the demographic issue than the causes of inequality.

There is one final point. We absolutely should be spending more money on daycare, healthcare for pregnant women and young children, early childhood education, and a variety of other areas that would benefit the young. However, there is no reason to believe that spending on the elderly is the obstacle preventing more spending in these areas.

[1] The median wage is taken from the Economic Policy Institute’s State of Working America data library. The 2022 was adjusted for the increase in the personal consumption expenditure deflator from 2022 to September of 2023 to get current dollars. Productivity growth since 1973 was adjusted for differences in deflators and the distinction between net and gross income, as well as the declining wage share of compensation to get the 2023 wage figure.

[2] Much of the projected shortfall in Social Security is a direct result of the upward redistribution of income since a larger share of wage income falls over the cap on taxable wage income (currently $186,600), as well as the shift from wages to profits in the last two decades.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Mark Twain famously quipped that everyone always talks about the weather, but no one ever does anything about it. (This was before global warming.) In the same vein, it is common for people to rant about billionaires, like Rupert Murdoch and Elon Musk, controlling major media outlets and using them to advance their political whims. But, no one seems to do anything about it.

There is a reason for inaction. For the foreseeable future, it is hard to envision a political scenario in which the ability of the rich and very rich to own and control major news outlets will be restricted. That means that if the goal is to prevent Elon Musk from owning Twitter (or “X,” as he now calls it), then we will likely be able to do little more than rant. (That is not entirely true.)

However, we can go the other way. We may not be able to stop the rich from owning major media outlets, but we can give a voice to everyone else. This can be done through a system of individual vouchers, where the government gives each person a sum, say $50, to support the news outlet of their choice.

One $50 voucher will not go far but thousands and millions of vouchers can support a lot of people doing journalism. The billionaires and the news outlets they control may still have more money, but there will be outlets they don’t control that will have the resources they need to do serious reporting that has a major impact.

If anyone doubts this point, just look at the work done by ProPublica or the Intercept in recent years. These two non-profit news outlets have broken story after story that were largely ignored by the major newspapers and television chains. (There are also many other great non-profit news organizations.)

ProPublica’s reporting is the reason that we know about Justice Clarence Thomas’ right-wing billionaire friends who buy him lavish vacations. But this important story is just the tip of the iceberg for the in-depth reporting they have done for more than a decade. The Intercept has also broken a wide range of stories that were neglected by corporate-owned news outlets, notably on political corruption and dubious foreign policy ventures.

The high-budget news outlets may spend tens or hundreds of millions pushing fluff stories and acting as public relations vehicles for their favored politicians, but serious news outlets can do important reporting on a fraction of their budgets. They don’t need to pay buffoonish news anchors millions of dollars a year. This is why a voucher system makes so much sense.

An individual voucher system also gets around the problem of having the government decide what news should be reported. It will be up to individuals to decide which outlets get their support.

The government would only set broad parameters, comparable to what it does now with the I.R.S. determining which organizations qualify for 501(c)3 status, so that contributors can get a deduction on their income taxes. The I.R.S. only makes a determination as to whether the organization is in fact a church, a shelter for the homeless, or a think tank, or whatever else they claim to do that qualifies for tax-exempt status. It doesn’t try to determine if they are a good church or think tank, that is done by their contributors.

It would be the same with the news voucher system. The agency administering the system would just determine whether the organization is in fact engaged in collecting and distributing news. It would be up to individuals to determine which organization gets their support.

At this point, there is little prospect of getting this sort of voucher system through at the national level, however, it can be done at the state or local level. Just last week, Washington, DC city council members Janeese Lewis George and Brianne Nadeau introduced a bill that would set aside $11 million (0.1 percent of the city budget) for individual vouchers to support local news reporting.

The way the program is structured is that the value of the voucher, or coupon, that each individual gets would depend on how many people use it. If only a thousand people used the vouchers, each person would have $11,000 to give to the news outlet of their choice. If 100,000 of DC’s residents (its population is just under 700,000) used the vouchers, each one would have $110 to support the local news they value.

A condition of getting the money would be that all the material produced would be posted on the web and available at no cost. The idea is that the public pays for news once, we don’t give people a subsidy through the voucher and then allow them to collect a second time by charging to get around a paywall.

A voucher program to support local news in DC may seem a long way from challenging the Murdochs and the Disneys for control of the media, but it is an important first step. And, what can be done in DC can be done in other cities. Mark Histed, with the group Democracy Policy Network, has been working with groups in other cities who have similar plans.

The point is that this has to start somewhere, and if this sort of voucher system can work in one city, it can work in others. And, if it is successful and the public values it, then we can envision a similar program could be introduced nationally at some point.

If this still sounds small bore, it is worth paying a bit of attention to what the right has managed to do over the years. The privatization of Medicare began under Reagan in the 1980s, as private insurers were allowed to get a slice of Medicare dollars. The privatization was expanded gradually over the years so that the current incarnation, Medicare Advantage, now covers 44 percent of all beneficiaries. More than half of new enrollees sign up for Medicare Advantage.

If we need another example of the success of the right in starting small and building up, we can just look at the current Congress. We have states like Wisconsin, that are relatively evenly balanced in votes in national elections. (Obama won twice, Trump won in 2016, and Biden won in 2020. It has one senator from each party.) Nonetheless, its congressional delegation has six Republicans and two Democrats.

This wasn’t the result of a magic trick. The Republicans worked to get people elected to the state’s legislature over the years. These legislators then gerrymandered districts (both their own and the congressional districts) to ensure that Republicans would have a share of seats that vastly exceeded their share of the votes. This resulted from years and decades of getting people to run for relatively boring positions in the state house or state senate. It has now paid big dividends for them in national politics.

It would be great if we could do something tomorrow that would drastically reduce the income and power imbalances that have exploded in the last half century. But the list of items that would do this and have a remote chance of getting anywhere politically is pretty close to zero.

Our choice is whether to do things that have an incremental impact and can grow through time, or empty ranting into the wind. The DC local news voucher program fits in the first category. People who really want to do something to reduce the power of billionaires should get behind it.

Mark Twain famously quipped that everyone always talks about the weather, but no one ever does anything about it. (This was before global warming.) In the same vein, it is common for people to rant about billionaires, like Rupert Murdoch and Elon Musk, controlling major media outlets and using them to advance their political whims. But, no one seems to do anything about it.

There is a reason for inaction. For the foreseeable future, it is hard to envision a political scenario in which the ability of the rich and very rich to own and control major news outlets will be restricted. That means that if the goal is to prevent Elon Musk from owning Twitter (or “X,” as he now calls it), then we will likely be able to do little more than rant. (That is not entirely true.)

However, we can go the other way. We may not be able to stop the rich from owning major media outlets, but we can give a voice to everyone else. This can be done through a system of individual vouchers, where the government gives each person a sum, say $50, to support the news outlet of their choice.

One $50 voucher will not go far but thousands and millions of vouchers can support a lot of people doing journalism. The billionaires and the news outlets they control may still have more money, but there will be outlets they don’t control that will have the resources they need to do serious reporting that has a major impact.

If anyone doubts this point, just look at the work done by ProPublica or the Intercept in recent years. These two non-profit news outlets have broken story after story that were largely ignored by the major newspapers and television chains. (There are also many other great non-profit news organizations.)

ProPublica’s reporting is the reason that we know about Justice Clarence Thomas’ right-wing billionaire friends who buy him lavish vacations. But this important story is just the tip of the iceberg for the in-depth reporting they have done for more than a decade. The Intercept has also broken a wide range of stories that were neglected by corporate-owned news outlets, notably on political corruption and dubious foreign policy ventures.

The high-budget news outlets may spend tens or hundreds of millions pushing fluff stories and acting as public relations vehicles for their favored politicians, but serious news outlets can do important reporting on a fraction of their budgets. They don’t need to pay buffoonish news anchors millions of dollars a year. This is why a voucher system makes so much sense.

An individual voucher system also gets around the problem of having the government decide what news should be reported. It will be up to individuals to decide which outlets get their support.

The government would only set broad parameters, comparable to what it does now with the I.R.S. determining which organizations qualify for 501(c)3 status, so that contributors can get a deduction on their income taxes. The I.R.S. only makes a determination as to whether the organization is in fact a church, a shelter for the homeless, or a think tank, or whatever else they claim to do that qualifies for tax-exempt status. It doesn’t try to determine if they are a good church or think tank, that is done by their contributors.

It would be the same with the news voucher system. The agency administering the system would just determine whether the organization is in fact engaged in collecting and distributing news. It would be up to individuals to determine which organization gets their support.

At this point, there is little prospect of getting this sort of voucher system through at the national level, however, it can be done at the state or local level. Just last week, Washington, DC city council members Janeese Lewis George and Brianne Nadeau introduced a bill that would set aside $11 million (0.1 percent of the city budget) for individual vouchers to support local news reporting.

The way the program is structured is that the value of the voucher, or coupon, that each individual gets would depend on how many people use it. If only a thousand people used the vouchers, each person would have $11,000 to give to the news outlet of their choice. If 100,000 of DC’s residents (its population is just under 700,000) used the vouchers, each one would have $110 to support the local news they value.

A condition of getting the money would be that all the material produced would be posted on the web and available at no cost. The idea is that the public pays for news once, we don’t give people a subsidy through the voucher and then allow them to collect a second time by charging to get around a paywall.

A voucher program to support local news in DC may seem a long way from challenging the Murdochs and the Disneys for control of the media, but it is an important first step. And, what can be done in DC can be done in other cities. Mark Histed, with the group Democracy Policy Network, has been working with groups in other cities who have similar plans.

The point is that this has to start somewhere, and if this sort of voucher system can work in one city, it can work in others. And, if it is successful and the public values it, then we can envision a similar program could be introduced nationally at some point.

If this still sounds small bore, it is worth paying a bit of attention to what the right has managed to do over the years. The privatization of Medicare began under Reagan in the 1980s, as private insurers were allowed to get a slice of Medicare dollars. The privatization was expanded gradually over the years so that the current incarnation, Medicare Advantage, now covers 44 percent of all beneficiaries. More than half of new enrollees sign up for Medicare Advantage.

If we need another example of the success of the right in starting small and building up, we can just look at the current Congress. We have states like Wisconsin, that are relatively evenly balanced in votes in national elections. (Obama won twice, Trump won in 2016, and Biden won in 2020. It has one senator from each party.) Nonetheless, its congressional delegation has six Republicans and two Democrats.

This wasn’t the result of a magic trick. The Republicans worked to get people elected to the state’s legislature over the years. These legislators then gerrymandered districts (both their own and the congressional districts) to ensure that Republicans would have a share of seats that vastly exceeded their share of the votes. This resulted from years and decades of getting people to run for relatively boring positions in the state house or state senate. It has now paid big dividends for them in national politics.

It would be great if we could do something tomorrow that would drastically reduce the income and power imbalances that have exploded in the last half century. But the list of items that would do this and have a remote chance of getting anywhere politically is pretty close to zero.

Our choice is whether to do things that have an incremental impact and can grow through time, or empty ranting into the wind. The DC local news voucher program fits in the first category. People who really want to do something to reduce the power of billionaires should get behind it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times ran an article with the unfortunate headline, “Ozempic and Wegovy don’t cost what you think they do.” The article goes on to explain that the drugs’ manufacturer, Novo Nordisk, gives discounts and rebates to the pharmacy benefit managers that purchase the bulk of prescription drugs, so the actual price paid is considerably less than the $900 to $1,300 retail price for a monthly dose. The article also tells readers that a number of other companies are developing drugs for obesity, so competition should be driving the price down further in the near future.

The True Cost of Ozempic and Wegovy

There are several important points that are overlooked in the article. First, these drugs don’t “cost” anywhere near what Novo Nordisk is charging, even after taking into account the discounts and rebates. In fact, they likely only cost around 1.0 percent of the retail price.

Novo Nordisk could probably cover the cost of manufacturing and distributing these drugs, and make a normal profit, if they sold them for $9-$13 dollars for a month’s dosage. Contrary to what is claimed in the headline, the NYT article is not referring to the drugs’ cost of production, it is referring to the price charged by Novo Nordisk.

The reason for the large gap between the price Novo Nordisk charges and its production costs is that the government has granted the company a patent monopoly. The government will arrest any company that manufactures Ozempic or Wegovy without Novo Nordisk’s permission.[1]

There is an enormous amount of money at stake with patent monopolies and related protections in the drug industry. We will spend over $600 billion this year on prescription and non-prescription drugs that would likely sell for around $100 billion in a free market without these protections. The difference of $500 billion comes to more than $4,000 a year per family. It’s roughly five times what the U.S. spends on food stamps each year.

Patent monopolies are also a big part of the story of upward redistribution in the U.S. over the last half-century. Patent and copyright monopolies likely shift more than $1 trillion a year from the rest of the population to the people in a position to benefit from these government protections.

It is often claimed that technology has been largely responsible for upward redistribution. In fact, it is our rules on technology that led to this upward redistribution. If the government did not give out patent and copyright monopolies, the gains from technology would be far more widely shared among the population. People like Bill Gates, who got incredibly rich from the patents and copyrights granted to Microsoft, would be far poorer with a free market.

There is a widely held myth that somehow people can’t be innovative if they work for a salary instead of the hope of getting rich by owning a patent monopoly. It’s not clear where this myth originated, but it is bizarre on its face.

There have been a huge number of great innovations from people working on salaries without any realistic hope of benefitting from a patent monopoly. According to a piece in the New York Times, Katalin Kariko, who just won a Nobel Prize for pioneering work in developing mRNA technology, spent most of her career going from lab to lab where she was supported by government grants. According to the piece, she never made more than $60,000 a year. While she has likely made a very substantial sum since the pandemic, due to her work with the German firm BioNTech, it is implausible that the expectation of this late-career bonanza was the motivating factor behind her earlier work.

Of course, the other major mRNA vaccine was developed by Moderna, operating under a government contract. (Incredibly, after paying for the development and the testing of the vaccine, the Trump administration also gave Moderna control of the vaccine, but presumably there was a sum that would have been sufficient to get Moderna to do the work without also giving them control of the vaccine.)

Government-granted Patent Monopolies Lead to Corruption #54,271

We just got another example of important work being done for pay when the American Prospect reported on how a former NIH employee appears to have developed a potentially important new cancer drug while working at the NIH. The scandal here is that Christian Hinrichs, the former NIH employee, appears to have established a company with a patent monopoly on a drug that he developed with NIH funding, which apparently also supported Phase I and II clinical trials of the drug.

This both demonstrates again the fact that people have no difficulty being innovative when being paid a salary, and also the sort of corruption that we see when the government grants patent monopolies. The second point should be apparent, but for some reason, it is never mentioned in major news outlets.

Every person who has been through an Econ 101 class can explain how a 25 percent tariff leads to corruption, since it raises the price of a product above its marginal cost. The same story would apply to patent monopolies, except by raising the price of drugs twenty or thirty times above the free market price, or even one hundred times the free market price, they are effectively tariffs of several thousand percent.

A patent monopoly encourages drug companies to push their drugs as widely as possible, even for uses where they might be inappropriate. It also gives them an incentive to conceal evidence that they might be ineffective or harmful. This is a substantial part of the story of the opioid crisis, where the major manufacturers concealed evidence that the new generation of opioids was highly addictive, as they encouraged doctors to prescribe them.

Patent monopolies can also lead to waste in research. As the NYT article notes, several other drug companies have obesity drugs in the pipeline, which presumably will be available soon. While this competition is beneficial in a context where drug companies have been granted patent monopolies, it would make little sense if drugs were being sold in a free market.

It is good to have multiple drugs to treat a condition, since not all people react the same way to a drug. Also, some drugs may not mix well with other drugs a patient is taking. Nonetheless, we will generally be better off devoting research to finding drugs for conditions where effective treatments do not already exist than developing multiple drugs for the same condition.

If we paid for research upfront, we could require that all results be fully open, so that researchers can quickly build on the research done by others. If there is a major breakthrough in a specific area, other researchers can then build on it and bring it to fruition more quickly.

They may also be able to identify pitfalls that could prevent researchers pursuing dead ends. For this reason, publicly funded open-research can potentially be far more efficient than patent monopoly supported research. Instead of encouraging secrecy, it would require openness.

Eliminating patent supported research could also put the pharmacy benefit manager industry out of business. If drugs sold at their free market price, it would make no more sense to have pharmacy benefit managers than to have paper plate benefit managers. These businesses survive and profit based on the large gap between the patent-protected price and the free market price. As this gap collapses, there would be no room for the industry to make profits and no need for the industry.

Drugs Are Cheap, Government-Granted Patent Monopolies Make Them Expensive

People who favor small government should be opposed to government-granted patent monopolies. The problem of high drug prices is caused by government interference in the free market. It would be much better for the economy and everyone’s health if we paid for the development of new drugs upfront and then let them be sold without protections. Unfortunately, the pharmaceutical industry is so powerful, it is almost impossible to get alternatives

[1] To be precise, Novo Nordisk would sue a company that produced these drugs without its permission. It would then get an injunction ordering them to stop production. If the company continued to produce the drugs in violation of the injunction, it would face criminal sanctions for violating an injunction, not for infringing on the patent.

The New York Times ran an article with the unfortunate headline, “Ozempic and Wegovy don’t cost what you think they do.” The article goes on to explain that the drugs’ manufacturer, Novo Nordisk, gives discounts and rebates to the pharmacy benefit managers that purchase the bulk of prescription drugs, so the actual price paid is considerably less than the $900 to $1,300 retail price for a monthly dose. The article also tells readers that a number of other companies are developing drugs for obesity, so competition should be driving the price down further in the near future.

The True Cost of Ozempic and Wegovy

There are several important points that are overlooked in the article. First, these drugs don’t “cost” anywhere near what Novo Nordisk is charging, even after taking into account the discounts and rebates. In fact, they likely only cost around 1.0 percent of the retail price.

Novo Nordisk could probably cover the cost of manufacturing and distributing these drugs, and make a normal profit, if they sold them for $9-$13 dollars for a month’s dosage. Contrary to what is claimed in the headline, the NYT article is not referring to the drugs’ cost of production, it is referring to the price charged by Novo Nordisk.

The reason for the large gap between the price Novo Nordisk charges and its production costs is that the government has granted the company a patent monopoly. The government will arrest any company that manufactures Ozempic or Wegovy without Novo Nordisk’s permission.[1]

There is an enormous amount of money at stake with patent monopolies and related protections in the drug industry. We will spend over $600 billion this year on prescription and non-prescription drugs that would likely sell for around $100 billion in a free market without these protections. The difference of $500 billion comes to more than $4,000 a year per family. It’s roughly five times what the U.S. spends on food stamps each year.

Patent monopolies are also a big part of the story of upward redistribution in the U.S. over the last half-century. Patent and copyright monopolies likely shift more than $1 trillion a year from the rest of the population to the people in a position to benefit from these government protections.

It is often claimed that technology has been largely responsible for upward redistribution. In fact, it is our rules on technology that led to this upward redistribution. If the government did not give out patent and copyright monopolies, the gains from technology would be far more widely shared among the population. People like Bill Gates, who got incredibly rich from the patents and copyrights granted to Microsoft, would be far poorer with a free market.

There is a widely held myth that somehow people can’t be innovative if they work for a salary instead of the hope of getting rich by owning a patent monopoly. It’s not clear where this myth originated, but it is bizarre on its face.

There have been a huge number of great innovations from people working on salaries without any realistic hope of benefitting from a patent monopoly. According to a piece in the New York Times, Katalin Kariko, who just won a Nobel Prize for pioneering work in developing mRNA technology, spent most of her career going from lab to lab where she was supported by government grants. According to the piece, she never made more than $60,000 a year. While she has likely made a very substantial sum since the pandemic, due to her work with the German firm BioNTech, it is implausible that the expectation of this late-career bonanza was the motivating factor behind her earlier work.

Of course, the other major mRNA vaccine was developed by Moderna, operating under a government contract. (Incredibly, after paying for the development and the testing of the vaccine, the Trump administration also gave Moderna control of the vaccine, but presumably there was a sum that would have been sufficient to get Moderna to do the work without also giving them control of the vaccine.)

Government-granted Patent Monopolies Lead to Corruption #54,271

We just got another example of important work being done for pay when the American Prospect reported on how a former NIH employee appears to have developed a potentially important new cancer drug while working at the NIH. The scandal here is that Christian Hinrichs, the former NIH employee, appears to have established a company with a patent monopoly on a drug that he developed with NIH funding, which apparently also supported Phase I and II clinical trials of the drug.

This both demonstrates again the fact that people have no difficulty being innovative when being paid a salary, and also the sort of corruption that we see when the government grants patent monopolies. The second point should be apparent, but for some reason, it is never mentioned in major news outlets.

Every person who has been through an Econ 101 class can explain how a 25 percent tariff leads to corruption, since it raises the price of a product above its marginal cost. The same story would apply to patent monopolies, except by raising the price of drugs twenty or thirty times above the free market price, or even one hundred times the free market price, they are effectively tariffs of several thousand percent.

A patent monopoly encourages drug companies to push their drugs as widely as possible, even for uses where they might be inappropriate. It also gives them an incentive to conceal evidence that they might be ineffective or harmful. This is a substantial part of the story of the opioid crisis, where the major manufacturers concealed evidence that the new generation of opioids was highly addictive, as they encouraged doctors to prescribe them.

Patent monopolies can also lead to waste in research. As the NYT article notes, several other drug companies have obesity drugs in the pipeline, which presumably will be available soon. While this competition is beneficial in a context where drug companies have been granted patent monopolies, it would make little sense if drugs were being sold in a free market.

It is good to have multiple drugs to treat a condition, since not all people react the same way to a drug. Also, some drugs may not mix well with other drugs a patient is taking. Nonetheless, we will generally be better off devoting research to finding drugs for conditions where effective treatments do not already exist than developing multiple drugs for the same condition.

If we paid for research upfront, we could require that all results be fully open, so that researchers can quickly build on the research done by others. If there is a major breakthrough in a specific area, other researchers can then build on it and bring it to fruition more quickly.

They may also be able to identify pitfalls that could prevent researchers pursuing dead ends. For this reason, publicly funded open-research can potentially be far more efficient than patent monopoly supported research. Instead of encouraging secrecy, it would require openness.

Eliminating patent supported research could also put the pharmacy benefit manager industry out of business. If drugs sold at their free market price, it would make no more sense to have pharmacy benefit managers than to have paper plate benefit managers. These businesses survive and profit based on the large gap between the patent-protected price and the free market price. As this gap collapses, there would be no room for the industry to make profits and no need for the industry.

Drugs Are Cheap, Government-Granted Patent Monopolies Make Them Expensive

People who favor small government should be opposed to government-granted patent monopolies. The problem of high drug prices is caused by government interference in the free market. It would be much better for the economy and everyone’s health if we paid for the development of new drugs upfront and then let them be sold without protections. Unfortunately, the pharmaceutical industry is so powerful, it is almost impossible to get alternatives

[1] To be precise, Novo Nordisk would sue a company that produced these drugs without its permission. It would then get an injunction ordering them to stop production. If the company continued to produce the drugs in violation of the injunction, it would face criminal sanctions for violating an injunction, not for infringing on the patent.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There have been numerous stories in the media about how the resumption this month of student loan repayments, after a three-and-a-half-year pandemic pause, will be a serious blow to the economy and tens of millions of borrowers. In fact, there was little basis for this concern, as a new analysis from the New York Federal Reserve Bank makes clear.

The study found that the vast majority of people facing repayment for the first time (people who finished school since the pandemic) would enter the new income-driven repayment plan developed by the Biden administration. More than half of the people who were already repaying their loans, are already in an income-based repayment plan, which is now considerably more generous.

As a practical matter, the idea that low-income borrowers would be devastated by loan payments is nonsense on its face. Under this plan, borrowers will pay nothing if their income is less than 225 percent of the poverty level for their family size. This means that a single person would pay zero if their income is less than $32,800. A person with one kid would pay zero if their income was less than $44,370.

Furthermore, they only pay 5 percent of their income on amounts above these cutoffs. This means that a single person with an income of $40,000 a year would face repayments of $360 a year or $30 a month. A person with one child and an income of $50,000 a year would have to pay $282 a year, or $23.50 a month.

If we up these figures to $50,000 for a single person or $60,000 for a person with one child, the annual payments would rise to $860 a year ($71.70 a month) and $782 a year ($65.20 a month). These figures may not be altogether trivial for moderate income households, but they also not likely to be devastating for most families.

It is also worth noting that under the Biden administration plan, the outstanding loan balance cannot increase even if borrowers are not covering their interest payment. In many cases, any unpaid balance will be forgiven after ten years in the plan. In the most of the rest it will be forgiven after 20 years.

The New York Fed survey asked borrowers how they expected the repayment requirement to affect their spending. On average, they expected that it would reduce their spending by $56 a month. With 28 million federal loan borrowers newly facing a repayment requirement, this comes to a reduction in monthly spending of $1.6 billion. That is a bit more than 0.1 percent of monthly consumption spending.

That sort of reduction in consumption spending will barely be noticeable in GDP measures. This limited impact was entirely predictable, it was unfortunate that many news outlets highlighted the prospect of resumed payments as a serious threat to the economy.

It is also unfortunate that more attention was not given to the Biden administration’s more generous income-driven loan repayment plan. Many borrowers have likely been worrying unnecessarily because they did not realize that they would pay little or nothing under the terms of the plan. It would be useful if the media did more to highlight the details of the Biden plan so that more borrowers are aware of the options available to them.

There have been numerous stories in the media about how the resumption this month of student loan repayments, after a three-and-a-half-year pandemic pause, will be a serious blow to the economy and tens of millions of borrowers. In fact, there was little basis for this concern, as a new analysis from the New York Federal Reserve Bank makes clear.

The study found that the vast majority of people facing repayment for the first time (people who finished school since the pandemic) would enter the new income-driven repayment plan developed by the Biden administration. More than half of the people who were already repaying their loans, are already in an income-based repayment plan, which is now considerably more generous.

As a practical matter, the idea that low-income borrowers would be devastated by loan payments is nonsense on its face. Under this plan, borrowers will pay nothing if their income is less than 225 percent of the poverty level for their family size. This means that a single person would pay zero if their income is less than $32,800. A person with one kid would pay zero if their income was less than $44,370.

Furthermore, they only pay 5 percent of their income on amounts above these cutoffs. This means that a single person with an income of $40,000 a year would face repayments of $360 a year or $30 a month. A person with one child and an income of $50,000 a year would have to pay $282 a year, or $23.50 a month.

If we up these figures to $50,000 for a single person or $60,000 for a person with one child, the annual payments would rise to $860 a year ($71.70 a month) and $782 a year ($65.20 a month). These figures may not be altogether trivial for moderate income households, but they also not likely to be devastating for most families.

It is also worth noting that under the Biden administration plan, the outstanding loan balance cannot increase even if borrowers are not covering their interest payment. In many cases, any unpaid balance will be forgiven after ten years in the plan. In the most of the rest it will be forgiven after 20 years.

The New York Fed survey asked borrowers how they expected the repayment requirement to affect their spending. On average, they expected that it would reduce their spending by $56 a month. With 28 million federal loan borrowers newly facing a repayment requirement, this comes to a reduction in monthly spending of $1.6 billion. That is a bit more than 0.1 percent of monthly consumption spending.

That sort of reduction in consumption spending will barely be noticeable in GDP measures. This limited impact was entirely predictable, it was unfortunate that many news outlets highlighted the prospect of resumed payments as a serious threat to the economy.

It is also unfortunate that more attention was not given to the Biden administration’s more generous income-driven loan repayment plan. Many borrowers have likely been worrying unnecessarily because they did not realize that they would pay little or nothing under the terms of the plan. It would be useful if the media did more to highlight the details of the Biden plan so that more borrowers are aware of the options available to them.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

If we want to be honest with ourselves and the people who bother to pay attention to what we say, we must acknowledge when we were wrong. I want to do that as clearly as possible. I repeatedly argued against the Fed’s path of rapid rate hikes. I was concerned that the rapid pace of rate hikes would lead to a sharp jump in unemployment.

Ostensibly, the Fed was looking to weaken the labor market (raise unemployment) as a way to reduce the pace of wage growth, and in that way slow inflation. I thought that inflation was likely to come down even without a big jump in unemployment, as the supply chain problems associated with the pandemic were resolved.

It seems that the Fed’s view of inflation was incorrect. The rate of inflation has fallen back nearly to the Fed’s 2.0 percent target, even as the unemployment rate remains below 4.0 percent.

However, I was very much mistaken on the impact of the Fed’s rate hikes. The unemployment rate today is 3.8 percent, only slightly higher than the 3.6 percent rate when it started raising rates in March of 2022. Clearly the Fed’s rate hikes did not have the disastrous impact on unemployment I feared.

Why Higher Rates Didn’t Raise Unemployment

It is possible to identify reasons why the rate hikes did not have as much impact as I and others expected. Usually rate hikes have their largest impact on housing construction.

While the rise in rates did sharply reduce the number of housing starts, from around 1.8 million at an annual rate last March to a bit over 1.3 million in recent months, it did not reduce the number of homes under construction. There were just over 1.6 million under construction when the Fed began raising rates. In recent months the number has been over 1.8 million. In keeping with this increase in homes under construction, employment in residential construction has actually risen since the Fed started raising rates.

The explanation for this seeming paradox is that there was a huge backlog of houses in the pipeline as a result of pandemic supply chain problems. This backlog will eventually be whittled down, but to date, the Fed’s rate hikes have not had the impact on residential construction that would ordinarily be expected.

The second area where Fed rate hikes generally have a large impact is on the trade deficit. This works through a rise in the value of the dollar. The dollar is supposed to rise in value relative to foreign currencies, as people buy dollars in order to take advantage of the high rates here.

This route hasn’t had the usual impact either. The main reason was that the dollar had already risen considerably against other major currencies before the Fed started raising rates. The dollar rose by roughly 10 percent against the euro and a comparable amount against the yen between the start of 2021 and the first Fed rate hike in 2022.

It has risen further against both currencies in the last year and a half, but the trade deficit has nonetheless fallen. It stood at 4.4 percent of GDP in the first quarter of 2022, it was down to 3.0 percent of GDP in the second quarter of this year.

The rise in the dollar surely had some effect in pushing the deficit higher, but this was likely swamped by the effect of consumers shifting away from buying goods following the end of the pandemic. At the height of the pandemic people were unwilling or unable to go to movies, concerts, or travel. As a result, when they spent money it was overwhelmingly on goods consumption, things like cars and TVs. A large share of these goods were imported.

As the impact of the pandemic waned, people shifted back towards buying services and spent a smaller share of their income on goods. The result has been a drop in the trade deficit.

Another area where we expect higher interest rates to have a large effect is on investment in non-residential structures. This category of investment tends to be more interest sensitive than shorter-lived assets, like equipment and software.

Here also the effect of the pandemic lessened the impact. Investment in structures had already fallen sharply, dropping from 3.2 percent of GDP in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 2.6 percent of GDP in the fourth quarter of 2021, a drop of close to 20 percent. Construction of office buildings and retail space fell through the floor as a result of the pandemic, as there was enormous over-supply in both areas.

This meant that as the Fed began raising rates in the spring of 2022 there was not much room for these areas to drop further. In addition, the Biden administration’s polices, notably the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act, spurred construction of factories producing semi-conductors, batteries, solar panels, and other items needed for a green transition.

These incentives swamped any negative impact from higher interest rates. Construction of factories was 65.9 percent higher in August of 2023 than in August of 2022. Structure investment now stands at 3.1 percent of GDP, almost back to its pre-pandemic share.

The peculiar situation created by the pandemic meant that higher interest rates could not have their normal effect in slowing growth and weakening the labor market. This is why the labor market has remained solid in spite of the sharpest set of rate hikes in more than forty years.

Negative Effects of Higher Interest Rates

Even though rate hikes have not produced the slowing that we would ordinarily expect, they still did have an effect on the economy. The big jump in interest rates essentially shut down mortgage refinancing. The low mortgage rates of the pandemic allowed roughly 14 million homeowners to refinance their mortgage between 2020 and 2022.

According to research from NY Federal Reserve Bank, five million of these borrowers took out a total of $430 billion in equity, which they used to support their consumption or invest in other assets. The other nine million borrowers saved an average of $2,500 a year on interest payments by refinancing at lower rates. Higher interest rates put an end to the refinancing boom, with refinancing down more than 90 percent from its pandemic peak.

Higher mortgage rates also put a squeeze on homebuying. Sales of existing homes are down by almost a third, more than 2 million at an annual rate, from their levels in February of 2022, before the Fed began raising rates. The drop in existing home sales does have some impact on the economy. When people buy a home it generates fees and commissions for realtors, mortgage issuers, and various other actors involved in a home sale. People often tend to buy things like refrigerators and dishwashers when they buy a house and possibly remodel or paint their new home. For this reason, the drop in existing home sales does slow growth, even if the impact is much smaller than would be the case with a comparable drop in the sale of new homes.

While this fall in spending is picked up in GDP, there is another aspect to the drop in home sales that is not picked up in our GDP measures. The reduction in home sales is mostly a story where people would like to sell their current home, and move to a new one, but are reluctant to do so because it would mean giving up a mortgage with a very low interest rate, and taking out a mortgage on a new home with a much higher interest rate. As a result, they put off moving to a home that might better fit their needs.

As was pointed out to me by Adam Ozimek, this is a real cost to higher interest rates that is not picked up in GDP. People who would otherwise be in a different home are unambiguously worse off as a result of high current mortgage rates. (A huge gain that is not picked up in GDP is the increase in the number of people working from home, who are saving thousands of dollars a year on commuting costs and hundreds of hours of commuting time. The number of people working from home has increased by more than 11 million since the pandemic.)

Another cost is that many smaller firms and start-ups are having more difficulty getting access to capital. This may not be a big deal in terms of current investment, but if many of these firms are more innovative than larger incumbent firms, we may be paying a price down the road in the form of less innovation and productivity growth.

And, we know that higher rates have produced stress in the financial system. The wave of bank failures that started with the collapse of the Silicon Valley Bank was a predictable outcome from the sort of sharp rise in interest rates we have seen over the last year and a half. While banks should have hedged themselves from interest rate risk, it is impossible to do so completely, and many financial institutions will be facing serious stress as long as rates are high.

Lowering Rates and Getting Back to Normal

For these reasons, it would be desirable to see the Fed start to turn the corner on interest rates. We don’t really need lower rates to boost the economy just now, we look to be on a healthy growth path for the foreseeable future. But we would nonetheless see substantial benefits from a decline in interest rates.

The lesson from the limited impact of the sharp rise in rates on growth should also apply in reverse. Lower rates will clearly have a positive impact on residential and non-residential construction, as well as the trade deficit, but the impact is not likely to be as large as previously believed. Just as was the case with the rise in rates, other factors are likely to be more important in determining demand in these areas.

To be clear, there is no reason for the Fed to do a sharp reversal on rates. The economy is not in desperate need of stimulus. But we should be looking to get back to something resembling normal following the steep pandemic recession and the sharp recovery. This means edging down to the sort of interest rate curve we saw before the pandemic. A statement of this intention by the Fed, along with a modest rate cut, would be a huge step in this direction.

If we want to be honest with ourselves and the people who bother to pay attention to what we say, we must acknowledge when we were wrong. I want to do that as clearly as possible. I repeatedly argued against the Fed’s path of rapid rate hikes. I was concerned that the rapid pace of rate hikes would lead to a sharp jump in unemployment.

Ostensibly, the Fed was looking to weaken the labor market (raise unemployment) as a way to reduce the pace of wage growth, and in that way slow inflation. I thought that inflation was likely to come down even without a big jump in unemployment, as the supply chain problems associated with the pandemic were resolved.

It seems that the Fed’s view of inflation was incorrect. The rate of inflation has fallen back nearly to the Fed’s 2.0 percent target, even as the unemployment rate remains below 4.0 percent.

However, I was very much mistaken on the impact of the Fed’s rate hikes. The unemployment rate today is 3.8 percent, only slightly higher than the 3.6 percent rate when it started raising rates in March of 2022. Clearly the Fed’s rate hikes did not have the disastrous impact on unemployment I feared.

Why Higher Rates Didn’t Raise Unemployment

It is possible to identify reasons why the rate hikes did not have as much impact as I and others expected. Usually rate hikes have their largest impact on housing construction.

While the rise in rates did sharply reduce the number of housing starts, from around 1.8 million at an annual rate last March to a bit over 1.3 million in recent months, it did not reduce the number of homes under construction. There were just over 1.6 million under construction when the Fed began raising rates. In recent months the number has been over 1.8 million. In keeping with this increase in homes under construction, employment in residential construction has actually risen since the Fed started raising rates.

The explanation for this seeming paradox is that there was a huge backlog of houses in the pipeline as a result of pandemic supply chain problems. This backlog will eventually be whittled down, but to date, the Fed’s rate hikes have not had the impact on residential construction that would ordinarily be expected.

The second area where Fed rate hikes generally have a large impact is on the trade deficit. This works through a rise in the value of the dollar. The dollar is supposed to rise in value relative to foreign currencies, as people buy dollars in order to take advantage of the high rates here.

This route hasn’t had the usual impact either. The main reason was that the dollar had already risen considerably against other major currencies before the Fed started raising rates. The dollar rose by roughly 10 percent against the euro and a comparable amount against the yen between the start of 2021 and the first Fed rate hike in 2022.

It has risen further against both currencies in the last year and a half, but the trade deficit has nonetheless fallen. It stood at 4.4 percent of GDP in the first quarter of 2022, it was down to 3.0 percent of GDP in the second quarter of this year.

The rise in the dollar surely had some effect in pushing the deficit higher, but this was likely swamped by the effect of consumers shifting away from buying goods following the end of the pandemic. At the height of the pandemic people were unwilling or unable to go to movies, concerts, or travel. As a result, when they spent money it was overwhelmingly on goods consumption, things like cars and TVs. A large share of these goods were imported.

As the impact of the pandemic waned, people shifted back towards buying services and spent a smaller share of their income on goods. The result has been a drop in the trade deficit.

Another area where we expect higher interest rates to have a large effect is on investment in non-residential structures. This category of investment tends to be more interest sensitive than shorter-lived assets, like equipment and software.

Here also the effect of the pandemic lessened the impact. Investment in structures had already fallen sharply, dropping from 3.2 percent of GDP in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 2.6 percent of GDP in the fourth quarter of 2021, a drop of close to 20 percent. Construction of office buildings and retail space fell through the floor as a result of the pandemic, as there was enormous over-supply in both areas.

This meant that as the Fed began raising rates in the spring of 2022 there was not much room for these areas to drop further. In addition, the Biden administration’s polices, notably the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act, spurred construction of factories producing semi-conductors, batteries, solar panels, and other items needed for a green transition.

These incentives swamped any negative impact from higher interest rates. Construction of factories was 65.9 percent higher in August of 2023 than in August of 2022. Structure investment now stands at 3.1 percent of GDP, almost back to its pre-pandemic share.

The peculiar situation created by the pandemic meant that higher interest rates could not have their normal effect in slowing growth and weakening the labor market. This is why the labor market has remained solid in spite of the sharpest set of rate hikes in more than forty years.

Negative Effects of Higher Interest Rates

Even though rate hikes have not produced the slowing that we would ordinarily expect, they still did have an effect on the economy. The big jump in interest rates essentially shut down mortgage refinancing. The low mortgage rates of the pandemic allowed roughly 14 million homeowners to refinance their mortgage between 2020 and 2022.

According to research from NY Federal Reserve Bank, five million of these borrowers took out a total of $430 billion in equity, which they used to support their consumption or invest in other assets. The other nine million borrowers saved an average of $2,500 a year on interest payments by refinancing at lower rates. Higher interest rates put an end to the refinancing boom, with refinancing down more than 90 percent from its pandemic peak.

Higher mortgage rates also put a squeeze on homebuying. Sales of existing homes are down by almost a third, more than 2 million at an annual rate, from their levels in February of 2022, before the Fed began raising rates. The drop in existing home sales does have some impact on the economy. When people buy a home it generates fees and commissions for realtors, mortgage issuers, and various other actors involved in a home sale. People often tend to buy things like refrigerators and dishwashers when they buy a house and possibly remodel or paint their new home. For this reason, the drop in existing home sales does slow growth, even if the impact is much smaller than would be the case with a comparable drop in the sale of new homes.

While this fall in spending is picked up in GDP, there is another aspect to the drop in home sales that is not picked up in our GDP measures. The reduction in home sales is mostly a story where people would like to sell their current home, and move to a new one, but are reluctant to do so because it would mean giving up a mortgage with a very low interest rate, and taking out a mortgage on a new home with a much higher interest rate. As a result, they put off moving to a home that might better fit their needs.

As was pointed out to me by Adam Ozimek, this is a real cost to higher interest rates that is not picked up in GDP. People who would otherwise be in a different home are unambiguously worse off as a result of high current mortgage rates. (A huge gain that is not picked up in GDP is the increase in the number of people working from home, who are saving thousands of dollars a year on commuting costs and hundreds of hours of commuting time. The number of people working from home has increased by more than 11 million since the pandemic.)

Another cost is that many smaller firms and start-ups are having more difficulty getting access to capital. This may not be a big deal in terms of current investment, but if many of these firms are more innovative than larger incumbent firms, we may be paying a price down the road in the form of less innovation and productivity growth.

And, we know that higher rates have produced stress in the financial system. The wave of bank failures that started with the collapse of the Silicon Valley Bank was a predictable outcome from the sort of sharp rise in interest rates we have seen over the last year and a half. While banks should have hedged themselves from interest rate risk, it is impossible to do so completely, and many financial institutions will be facing serious stress as long as rates are high.

Lowering Rates and Getting Back to Normal

For these reasons, it would be desirable to see the Fed start to turn the corner on interest rates. We don’t really need lower rates to boost the economy just now, we look to be on a healthy growth path for the foreseeable future. But we would nonetheless see substantial benefits from a decline in interest rates.