Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Donald Trump’s bluster about imposing large tariffs and forcing companies to make things in America has led to backlash where we have people saying things to the effect that we are in a global economy and we just can’t do anything about shifting from foreign produced items to domestically produced items. Paul Krugman’s blog post on trade can be seen in this light, although it is not exactly what he said and he surely knows better.

The post points out that imports account for a large percentage of the cost of many of the goods we produce here. This means that if we raise the price of imports, we also make it more expensive to produce goods in the United States.

This is of course true, but that doesn’t mean that higher import prices would not lead to a shift towards domestic production. For example, if we take the case of transport equipment he highlights, if all the parts that we imported cost 20 percent more, then over time we would expect car producers in the United States to produce with a larger share of domestically produced parts than would otherwise be the case. This doesn’t mean that imported parts go to zero, or even that they necessarily fall, but just that they would be less than would be the case if import prices were 20 percent lower. This is pretty much basic economics — at a higher price we buy less.

While arbitrary tariffs are not a good way to raise the relative price of imports, we do have an obvious tool that is designed for exactly this purpose. We can reduce the value of the dollar against the currencies of our trading partners. This is probably best done through negotiations, which would inevitably involve trade-offs (e.g. less pressure to enforce U.S. patents and copyrights and less concern about access for the U.S. financial industry). Loud threats against our trading partners are likely to prove counter-productive. (We should also remove the protectionist barriers that keep our doctors and dentists from enjoying the full benefits of international competition.)

Anyhow, we can do something about our trade deficits if we had a president who thought seriously about the issue. As it is, the current occupant of the White House seems to not know which way is up when it comes to trade.

Donald Trump’s bluster about imposing large tariffs and forcing companies to make things in America has led to backlash where we have people saying things to the effect that we are in a global economy and we just can’t do anything about shifting from foreign produced items to domestically produced items. Paul Krugman’s blog post on trade can be seen in this light, although it is not exactly what he said and he surely knows better.

The post points out that imports account for a large percentage of the cost of many of the goods we produce here. This means that if we raise the price of imports, we also make it more expensive to produce goods in the United States.

This is of course true, but that doesn’t mean that higher import prices would not lead to a shift towards domestic production. For example, if we take the case of transport equipment he highlights, if all the parts that we imported cost 20 percent more, then over time we would expect car producers in the United States to produce with a larger share of domestically produced parts than would otherwise be the case. This doesn’t mean that imported parts go to zero, or even that they necessarily fall, but just that they would be less than would be the case if import prices were 20 percent lower. This is pretty much basic economics — at a higher price we buy less.

While arbitrary tariffs are not a good way to raise the relative price of imports, we do have an obvious tool that is designed for exactly this purpose. We can reduce the value of the dollar against the currencies of our trading partners. This is probably best done through negotiations, which would inevitably involve trade-offs (e.g. less pressure to enforce U.S. patents and copyrights and less concern about access for the U.S. financial industry). Loud threats against our trading partners are likely to prove counter-productive. (We should also remove the protectionist barriers that keep our doctors and dentists from enjoying the full benefits of international competition.)

Anyhow, we can do something about our trade deficits if we had a president who thought seriously about the issue. As it is, the current occupant of the White House seems to not know which way is up when it comes to trade.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The inflation hawks are getting restless. They are anxious to seize on any evidence of rising inflation as an opportunity to push the Fed to raise interest rates.

For this reason, many may be excited by the latest data from the Commerce Department showing that the overall PCE deflator is up 2.1 percent over the last year, with the core (excluding food and energy prices) rising by 1.8 percent. As the headline of the AP article carried by the New York Times put it, “consumer spending slows; inflation pushing higher.”

The case for a rise in the inflation rate is a bit weaker if we move out a decimal. The inflation rate in the core PCE deflator over the last year was 1.753 percent. This rounds up to 1.8 percent, but not by much.

Furthermore, this is a rent story. The rent component of the PCE has risen by 3.6 percent over the last year. If we pull this out, inflation in the core PCE would be just 1.3 percent over the last 12 months. That’s not a lot to get excited over.

The inflation hawks are getting restless. They are anxious to seize on any evidence of rising inflation as an opportunity to push the Fed to raise interest rates.

For this reason, many may be excited by the latest data from the Commerce Department showing that the overall PCE deflator is up 2.1 percent over the last year, with the core (excluding food and energy prices) rising by 1.8 percent. As the headline of the AP article carried by the New York Times put it, “consumer spending slows; inflation pushing higher.”

The case for a rise in the inflation rate is a bit weaker if we move out a decimal. The inflation rate in the core PCE deflator over the last year was 1.753 percent. This rounds up to 1.8 percent, but not by much.

Furthermore, this is a rent story. The rent component of the PCE has risen by 3.6 percent over the last year. If we pull this out, inflation in the core PCE would be just 1.3 percent over the last 12 months. That’s not a lot to get excited over.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Marketplace radio had a peculiar piece asking what the world would have looked like if NAFTA never had been signed. The piece is odd because it dismisses job concerns associated with NAFTA by telling readers that automation (i.e. productivity growth) has been far more important in costing jobs.

“As in, ATMs replacing bankers, robots displacing welders. Automation is a very old story that goes back 250 years, but it has really picked up in the last couple decades.

“‘We economic developers have an old joke,’ said Charles Hayes of the Research Triangle Regional Partnership in an interview with Marketplace in 2010. ‘The manufacturing facility of the future will employ two people: one will be a man, and one will be a dog. And the man will be there to feed the dog. And the dog will be there to make sure the man doesn’t touch the equipment.’

“Ouch. But it turns out technology replaced workers in the course of reporting this very story.”

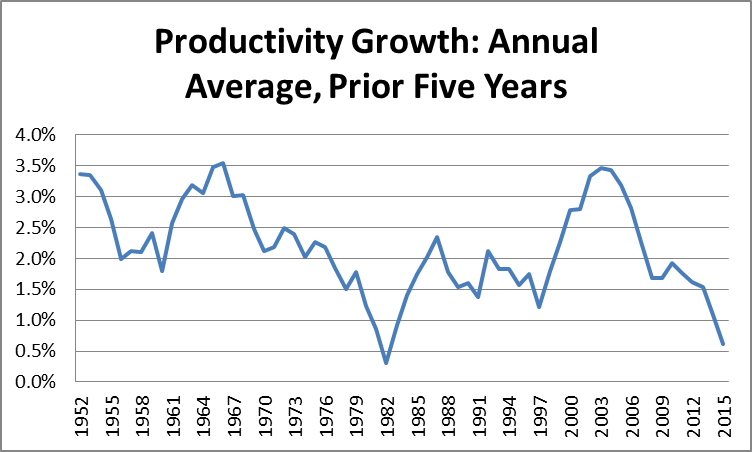

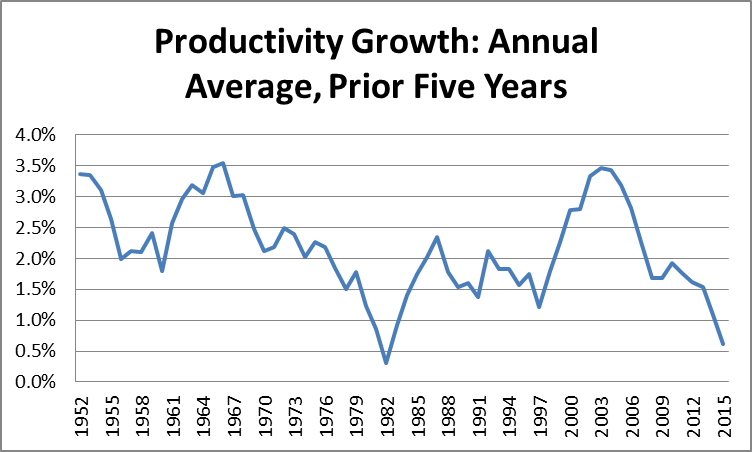

Actually, the Bureau of Labor Statistics tells us the opposite. Productivity growth did pick up from 1995 to 2005, rising back to its 1947 to 1973 Golden Age pace (a period of low unemployment and rapidly rising wages), but has slowed sharply in the last dozen years.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

While more rapid productivity growth would allow for faster wage and overall economic growth, no one has a very clear path for raising the rate of productivity growth. It is strange that Marketplace thinks our problem is a too rapid pace of productivity growth.

The piece is right in saying that the jobs impact of NAFTA was relatively limited. Certainly trade with China displaced many more workers. NAFTA may nonetheless have had a negative impact on the wages of many manufacturing workers. It made the threat to move operations to Mexico far more credible and many employers took advantage of this opportunity to discourage workers from joining unions and to make wage concessions. It’s surprising that the piece did not discuss this effect of NAFTA.

Marketplace radio had a peculiar piece asking what the world would have looked like if NAFTA never had been signed. The piece is odd because it dismisses job concerns associated with NAFTA by telling readers that automation (i.e. productivity growth) has been far more important in costing jobs.

“As in, ATMs replacing bankers, robots displacing welders. Automation is a very old story that goes back 250 years, but it has really picked up in the last couple decades.

“‘We economic developers have an old joke,’ said Charles Hayes of the Research Triangle Regional Partnership in an interview with Marketplace in 2010. ‘The manufacturing facility of the future will employ two people: one will be a man, and one will be a dog. And the man will be there to feed the dog. And the dog will be there to make sure the man doesn’t touch the equipment.’

“Ouch. But it turns out technology replaced workers in the course of reporting this very story.”

Actually, the Bureau of Labor Statistics tells us the opposite. Productivity growth did pick up from 1995 to 2005, rising back to its 1947 to 1973 Golden Age pace (a period of low unemployment and rapidly rising wages), but has slowed sharply in the last dozen years.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

While more rapid productivity growth would allow for faster wage and overall economic growth, no one has a very clear path for raising the rate of productivity growth. It is strange that Marketplace thinks our problem is a too rapid pace of productivity growth.

The piece is right in saying that the jobs impact of NAFTA was relatively limited. Certainly trade with China displaced many more workers. NAFTA may nonetheless have had a negative impact on the wages of many manufacturing workers. It made the threat to move operations to Mexico far more credible and many employers took advantage of this opportunity to discourage workers from joining unions and to make wage concessions. It’s surprising that the piece did not discuss this effect of NAFTA.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Morning Edition had a segment on Republican efforts to repeal Obamacare which reported on the desire of many Republican members of Congress to reduce the number of essential health benefits that must be covered by insurance. While the piece noted that part of the reason for the required benefits is to ensure people are covered in important areas, this is probably the less important reason for imposing requirements.

If people are allowed to pick and choose what conditions get covered, many more healthy people may opt for plans that cover few conditions and cost very little. If this happens, then plans that offer more comprehensive coverage will have a less healthy pool of beneficiaries, and therefore have to charge high fees. This will make insurance unaffordable for the people who most need it.

Morning Edition had a segment on Republican efforts to repeal Obamacare which reported on the desire of many Republican members of Congress to reduce the number of essential health benefits that must be covered by insurance. While the piece noted that part of the reason for the required benefits is to ensure people are covered in important areas, this is probably the less important reason for imposing requirements.

If people are allowed to pick and choose what conditions get covered, many more healthy people may opt for plans that cover few conditions and cost very little. If this happens, then plans that offer more comprehensive coverage will have a less healthy pool of beneficiaries, and therefore have to charge high fees. This will make insurance unaffordable for the people who most need it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s great that there are so many jobs for mind readers in the media. This morning Tamara Keith used her talents in this area to tell listeners that members of the Republican “Freedom Caucus” in the House “believe” that reducing the areas of mandated coverage is the key to reducing the cost of insurance.

It’s good that we have someone who can tell us what these Freedom Caucus members really believe. Otherwise, many people might think that they were trying to reduce the areas of mandated coverage in order to allow healthy people to avoid subsidizing less healthy people.

Someone in good health can buy a plan with very little coverage, since odds are they will not need coverage for most conditions. These plans would be relatively low cost, since they are paying out little in benefits. On the other hand, plans that did cover more conditions would be extremely expensive and unaffordable to most people. If we didn’t have a NPR mind reader to tell us otherwise, we might think that this is the situation that the Freedom Caucus members are trying to bring about.

It’s great that there are so many jobs for mind readers in the media. This morning Tamara Keith used her talents in this area to tell listeners that members of the Republican “Freedom Caucus” in the House “believe” that reducing the areas of mandated coverage is the key to reducing the cost of insurance.

It’s good that we have someone who can tell us what these Freedom Caucus members really believe. Otherwise, many people might think that they were trying to reduce the areas of mandated coverage in order to allow healthy people to avoid subsidizing less healthy people.

Someone in good health can buy a plan with very little coverage, since odds are they will not need coverage for most conditions. These plans would be relatively low cost, since they are paying out little in benefits. On the other hand, plans that did cover more conditions would be extremely expensive and unaffordable to most people. If we didn’t have a NPR mind reader to tell us otherwise, we might think that this is the situation that the Freedom Caucus members are trying to bring about.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión