Binyamin Appelbaum had a good piece in the NYT presenting how mainstream economists assess the prospects for boosting growth with the sort of tax cuts proposed by the Trump administration. While the piece accurately conveys the range of views among the mainstream of the profession about the extent to which it is possible to boost GDP growth, it is worth noting that the mainstream of the profession has an absolutely horrible track record in this area.

The piece tells us that the Federal Reserve Board puts the economy’s potential growth rate at just 1.8 percent a year. It then presents views of several economists suggesting that a well-designed tax reform could raise this by 0.3 to 0.5 percentage points.

As recently as 2012, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the economy could grow at a 2.5 percent annual rate for the period between 2018 and 2022 (see Summary Table 2). CBO’s projections are usually near the center of the economic mainstream, so in the not distant past, many economists believed that the economy could sustain a 2.5 percent annual rate of growth.

It is also worth noting that there is enormous uncertainty about how low the unemployment rate can go without sparking inflation. CBO put the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) in the 5.2–5.4 percent range five years ago. In the most recent month, the unemployment rate was 4.4 percent. There is no evidence in the data of any acceleration in the rate of inflation.

This is important background. While it is probably true that the sort of tax reform proposed by Trump (i.e. giving rich people more money and creating more opportunities to game the tax code) will not provide much boost to growth, economists really don’t have much basis for confidence in their own projections of the economy’s potential. They have repeatedly been wrong by huge amounts in the past, so unless they suddenly learned a great deal of economics, we should view current projections with considerable skepticism.

Binyamin Appelbaum had a good piece in the NYT presenting how mainstream economists assess the prospects for boosting growth with the sort of tax cuts proposed by the Trump administration. While the piece accurately conveys the range of views among the mainstream of the profession about the extent to which it is possible to boost GDP growth, it is worth noting that the mainstream of the profession has an absolutely horrible track record in this area.

The piece tells us that the Federal Reserve Board puts the economy’s potential growth rate at just 1.8 percent a year. It then presents views of several economists suggesting that a well-designed tax reform could raise this by 0.3 to 0.5 percentage points.

As recently as 2012, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the economy could grow at a 2.5 percent annual rate for the period between 2018 and 2022 (see Summary Table 2). CBO’s projections are usually near the center of the economic mainstream, so in the not distant past, many economists believed that the economy could sustain a 2.5 percent annual rate of growth.

It is also worth noting that there is enormous uncertainty about how low the unemployment rate can go without sparking inflation. CBO put the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) in the 5.2–5.4 percent range five years ago. In the most recent month, the unemployment rate was 4.4 percent. There is no evidence in the data of any acceleration in the rate of inflation.

This is important background. While it is probably true that the sort of tax reform proposed by Trump (i.e. giving rich people more money and creating more opportunities to game the tax code) will not provide much boost to growth, economists really don’t have much basis for confidence in their own projections of the economy’s potential. They have repeatedly been wrong by huge amounts in the past, so unless they suddenly learned a great deal of economics, we should view current projections with considerable skepticism.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

As I like to point out, debates on economic policy suffer badly from the “which way is up problem.” At the same time we are constantly hearing concerns about aging baby boomers and large budget deficits (too little supply and too much demand) we also hear stories about robots displacing workers and creating mass unemployment (too much supply and too little demand).

Either of these stories could, in principle, be true, but they can’t possibly both be true at the same time. It speaks volumes for the confusion perpetuated in public debates that we do simultaneously hear both concerns raises. (I was once on a radio show where the other person was warning about robots taking all the jobs. He then said things will get even worse when the baby boomers retire and we have to pay for Social Security. Just think, we first have no jobs and then have no workers.)

Anyhow, the NYT had a story about a state-of-the-art auto factory in China which relies largely on robots to put together cars. This is interesting because there have been numerous stories about how China is going to meet some terrible fate as a result of its one child policy, which sharply curtailed population growth. Its labor force is projected to shrink over the next two decades.

In fact, there is basically zero reason for China to be worried about its shrinking labor force. China still has tens of millions of people employed in extremely low productivity agricultural work. It also has many older factories with outmoded technologies. These can be readily replaced with new factories, like the one highlighted here, which will have much higher productivity.

In short, there is pretty much nothing to the China labor shortage story. But on the plus side, many economists can be employed talking about it.

As I like to point out, debates on economic policy suffer badly from the “which way is up problem.” At the same time we are constantly hearing concerns about aging baby boomers and large budget deficits (too little supply and too much demand) we also hear stories about robots displacing workers and creating mass unemployment (too much supply and too little demand).

Either of these stories could, in principle, be true, but they can’t possibly both be true at the same time. It speaks volumes for the confusion perpetuated in public debates that we do simultaneously hear both concerns raises. (I was once on a radio show where the other person was warning about robots taking all the jobs. He then said things will get even worse when the baby boomers retire and we have to pay for Social Security. Just think, we first have no jobs and then have no workers.)

Anyhow, the NYT had a story about a state-of-the-art auto factory in China which relies largely on robots to put together cars. This is interesting because there have been numerous stories about how China is going to meet some terrible fate as a result of its one child policy, which sharply curtailed population growth. Its labor force is projected to shrink over the next two decades.

In fact, there is basically zero reason for China to be worried about its shrinking labor force. China still has tens of millions of people employed in extremely low productivity agricultural work. It also has many older factories with outmoded technologies. These can be readily replaced with new factories, like the one highlighted here, which will have much higher productivity.

In short, there is pretty much nothing to the China labor shortage story. But on the plus side, many economists can be employed talking about it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In his presidential campaign, Donald Trump made a big point of beating up on China for its “currency manipulation.” He said that China was ripping off the United States because of its large trade surplus with the U.S., which had cost us millions of manufacturing jobs.

Trump said the trade deficit was due to the fact that our “stupid” trade negotiators allowed China to get away with depressing the value of the yuan against the dollar. This makes Chinese goods relatively cheaper in world markets, giving them a competitive advantage. Trump promised to put an end to this currency manipulation.

Last month, Trump met with China’s President Xi Jinping. According to his own account, the topic of currency values did not come up. Trump said that he got along very well with President Xi and looked forward to his assistance in dealing with North Korea. He didn’t want to spoil the relationship by bringing up currency.

The Washington Post today reported on a trade deal the Trump administration worked out with China. The piece says that the deal will open the door for beef exports to China. It also will remove obstacles that prevented U.S. financial services companies (e.g. Goldman Sachs) from operating in China. This agreement is undoubtedly good news for beef exporters, even if the impact is exaggerated (it might trivially raise the price of U.S. beef) and it surely is good news for the financial industry, but it doesn’t do anything for the manufacturing workers who lost their jobs in places like Ohio and Pennsylvania.

In his presidential campaign, Donald Trump made a big point of beating up on China for its “currency manipulation.” He said that China was ripping off the United States because of its large trade surplus with the U.S., which had cost us millions of manufacturing jobs.

Trump said the trade deficit was due to the fact that our “stupid” trade negotiators allowed China to get away with depressing the value of the yuan against the dollar. This makes Chinese goods relatively cheaper in world markets, giving them a competitive advantage. Trump promised to put an end to this currency manipulation.

Last month, Trump met with China’s President Xi Jinping. According to his own account, the topic of currency values did not come up. Trump said that he got along very well with President Xi and looked forward to his assistance in dealing with North Korea. He didn’t want to spoil the relationship by bringing up currency.

The Washington Post today reported on a trade deal the Trump administration worked out with China. The piece says that the deal will open the door for beef exports to China. It also will remove obstacles that prevented U.S. financial services companies (e.g. Goldman Sachs) from operating in China. This agreement is undoubtedly good news for beef exporters, even if the impact is exaggerated (it might trivially raise the price of U.S. beef) and it surely is good news for the financial industry, but it doesn’t do anything for the manufacturing workers who lost their jobs in places like Ohio and Pennsylvania.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The betting still seems to be that the Fed will raise rates in June, but it doesn’t seem like the inflation data could be the reason. The numbers were again quite tame in April, with the overall CPI increasing by 0.2 percent in the month and the core by 0.1 percent. The year over year increase in the overall CPI is 2.2 percent, and 1.9 percent in the core. This puts inflation well below the 2.0 percent average rate (for the PCE deflator) being targeted by the Fed.

However, the weakness of inflation is even more striking if we look at a core CPI that excludes shelter. There is a logic to this, since shelter does not follow the same dynamic as other components in the CPI. Furthermore, the Fed is not going to reduce shelter costs by raising interest rates. In fact, by slowing construction and thereby reducing supply, it could well be raising shelter costs.

Here’s the picture.

The rate of inflation in this non-shelter core is 0.8 percent over the last year. Perhaps even more importantly, it is falling, not rising. This means that the extremely weak evidence of any acceleration in core inflation was completely due to rising rents. If we pull out housing, the rate of inflation in everything else is declining.

So why does the Fed feel it has to raise rates?

The betting still seems to be that the Fed will raise rates in June, but it doesn’t seem like the inflation data could be the reason. The numbers were again quite tame in April, with the overall CPI increasing by 0.2 percent in the month and the core by 0.1 percent. The year over year increase in the overall CPI is 2.2 percent, and 1.9 percent in the core. This puts inflation well below the 2.0 percent average rate (for the PCE deflator) being targeted by the Fed.

However, the weakness of inflation is even more striking if we look at a core CPI that excludes shelter. There is a logic to this, since shelter does not follow the same dynamic as other components in the CPI. Furthermore, the Fed is not going to reduce shelter costs by raising interest rates. In fact, by slowing construction and thereby reducing supply, it could well be raising shelter costs.

Here’s the picture.

The rate of inflation in this non-shelter core is 0.8 percent over the last year. Perhaps even more importantly, it is falling, not rising. This means that the extremely weak evidence of any acceleration in core inflation was completely due to rising rents. If we pull out housing, the rate of inflation in everything else is declining.

So why does the Fed feel it has to raise rates?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I’ve had people ask me, so I went back to refresh my memory. Yes, it was very bad news as the Watergate scandal unfolded and Nixon was eventually forced to resign. The economy slipped into a recession beginning in November of 1973, with the unemployment rate rising from a low of 4.6 percent in October of 1973 to an eventual peak of 9.0 percent in May of 1975.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Having put these numbers on the table, I’m not sure how much of this can be attributed to Watergate and the crisis of the Nixon presidency. The proximate cause was the Arab oil embargo which quadrupled the price of oil at a time when the U.S. was far more dependent on oil than is currently the case. Nixon also removed the wage and controls which were intended to keep inflation under control through the 1972 election. Throw in a wheat deal with the Soviet Union that sent wheat prices soaring and you have a serious inflation problem.

The Fed responded by slamming on the brakes which gave us at the time what was considered to be a pretty awful recession. Would Nixon have done anything to save the economy if he wasn’t struggling to save his presidency? It’s hard to say to say what he could or would have done, but the story as it played out was not pretty.

I’ve had people ask me, so I went back to refresh my memory. Yes, it was very bad news as the Watergate scandal unfolded and Nixon was eventually forced to resign. The economy slipped into a recession beginning in November of 1973, with the unemployment rate rising from a low of 4.6 percent in October of 1973 to an eventual peak of 9.0 percent in May of 1975.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Having put these numbers on the table, I’m not sure how much of this can be attributed to Watergate and the crisis of the Nixon presidency. The proximate cause was the Arab oil embargo which quadrupled the price of oil at a time when the U.S. was far more dependent on oil than is currently the case. Nixon also removed the wage and controls which were intended to keep inflation under control through the 1972 election. Throw in a wheat deal with the Soviet Union that sent wheat prices soaring and you have a serious inflation problem.

The Fed responded by slamming on the brakes which gave us at the time what was considered to be a pretty awful recession. Would Nixon have done anything to save the economy if he wasn’t struggling to save his presidency? It’s hard to say to say what he could or would have done, but the story as it played out was not pretty.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

We hear endless stories in the media about how the robots are taking all the jobs. There was a new rush of such stories after the release of a study by Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, which found that robots were responsible for a substantial share of the job loss in manufacturing in the last decade. (For example, this Bloomberg piece by Mira Rojanasakul and Peter Coy.)

However, there remains a very basic problem in the robot story, it is not showing up in the productivity data. To step back a minute, robots are supposed to replace human labor. This means that for the same number of hours of human work, we should see much higher output of goods and services, since the robots are now adding to total output. This is what productivity growth means.

So if robots are having a large impact on jobs, then we should see productivity growth going through the roof. Instead, it is falling through the floor. It has averaged less than 1.0 percent annually in the last decade. This compares to an average growth rate of 3.0 percent in the decade from 1995 to 2005 and also in the long Golden Age from 1947 to 1973.

Strikingly, productivity growth has been especially bad in manufacturing, the place where we see the greatest use of robots. Here’s the picture since 1988, the period for which the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has a consistent series.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Over the last four years productivity growth in manufacturing averaged less than 0.2 percent annually. This compares to rates that often exceeded 4.0 percent in prior decades. This slowdown is especially striking since the rate of installation has increased sharply in recent years. According to data cited in the Bloomberg piece, we’ve added an average of 22,000 robots a year in the last three years. This compares to a peak of around 16,000 in the years before the Great Recession.

If robots are leading to massive job loss, then we should be seeing some serious gains in productivity. Instead the opposite has occurred. It’s awful to let a good story be ruined by evidence, but it just doesn’t seem that the use of robots will go far towards explaining the weakness of wage and job growth in the recovery.

We hear endless stories in the media about how the robots are taking all the jobs. There was a new rush of such stories after the release of a study by Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, which found that robots were responsible for a substantial share of the job loss in manufacturing in the last decade. (For example, this Bloomberg piece by Mira Rojanasakul and Peter Coy.)

However, there remains a very basic problem in the robot story, it is not showing up in the productivity data. To step back a minute, robots are supposed to replace human labor. This means that for the same number of hours of human work, we should see much higher output of goods and services, since the robots are now adding to total output. This is what productivity growth means.

So if robots are having a large impact on jobs, then we should see productivity growth going through the roof. Instead, it is falling through the floor. It has averaged less than 1.0 percent annually in the last decade. This compares to an average growth rate of 3.0 percent in the decade from 1995 to 2005 and also in the long Golden Age from 1947 to 1973.

Strikingly, productivity growth has been especially bad in manufacturing, the place where we see the greatest use of robots. Here’s the picture since 1988, the period for which the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has a consistent series.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Over the last four years productivity growth in manufacturing averaged less than 0.2 percent annually. This compares to rates that often exceeded 4.0 percent in prior decades. This slowdown is especially striking since the rate of installation has increased sharply in recent years. According to data cited in the Bloomberg piece, we’ve added an average of 22,000 robots a year in the last three years. This compares to a peak of around 16,000 in the years before the Great Recession.

If robots are leading to massive job loss, then we should be seeing some serious gains in productivity. Instead the opposite has occurred. It’s awful to let a good story be ruined by evidence, but it just doesn’t seem that the use of robots will go far towards explaining the weakness of wage and job growth in the recovery.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post has long pushed the view that a dollar (or euro) that is in the pocket of a middle-class person is a dollar that should be in the pockets of the rich. (They are okay with crumbs for the poor.) In keeping with this position, in its lead editorial today the Post complained about the “sclerotic statism” of the French economy. It then called for increasing employment, “through reforms of the labor code, not by protectionism or restriction of immigration.”

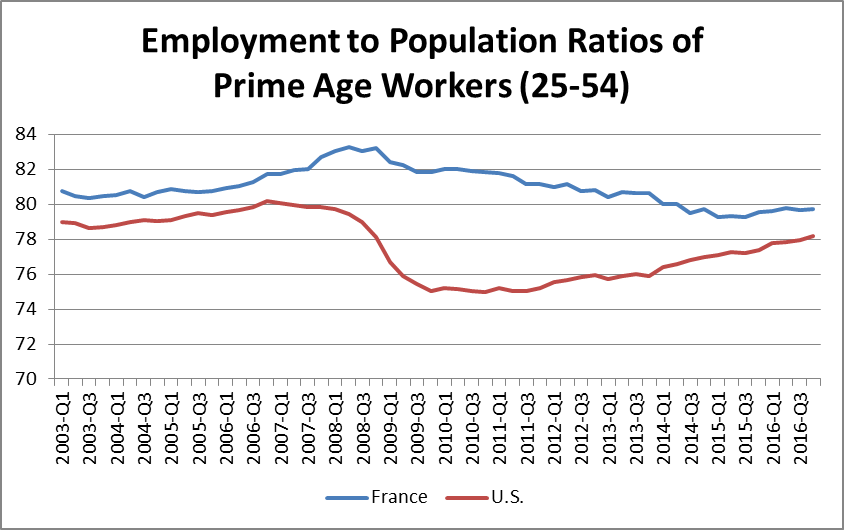

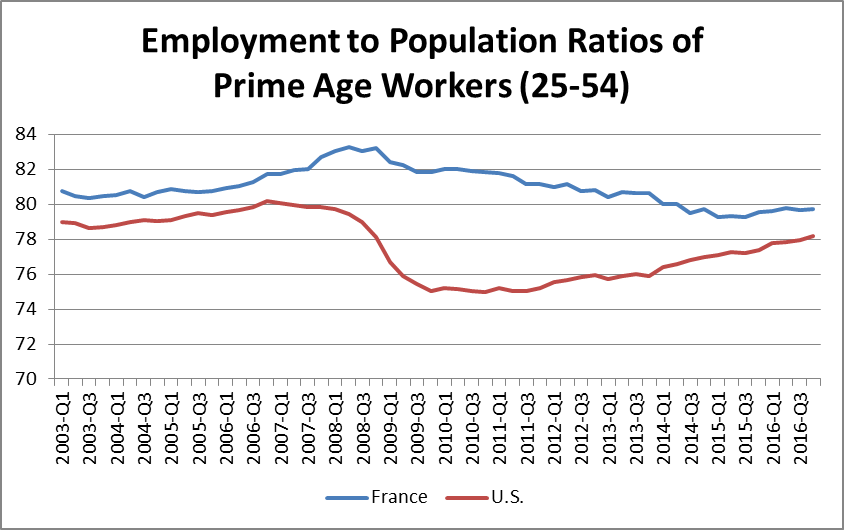

It is worth bringing a little bit of data to the fact free zone of the Washington Post opinion pages. France actually has consistently had a higher employment rate for its prime-age workers (ages 25 to 54) than the United States.

As can be seen, the employment rate for prime-age workers in France was roughly 2 percentage points higher in 2003. The gap expanded to almost 7 percentage points following the downturn, but it has in more recent years narrowed again to just under 2 percentage points.

France does have much lower employment rates among younger and older workers than the United States, but this is due to policy choices. College is largely free in France and students get stipends from the government. Therefore, many fewer young people work. France also makes it much easier for people to retire in their early sixties than in the United States, with largely free health care and earlier pensions. The merits of these policies can be debated, but they are not evidence of a sclerotic economy.

It is also not clear that the Washington Post’s desire to weaken protections for workers (euphemistically described as “reforms of the labor code”) will have a significant effect in reducing unemployment or raising employment. Extensive research has shown there is little relationship between worker protections and employment. It is also worth noting that the Post denounced protectionism in this editorial, but it is fine with protectionism in the form of ever longer and stronger copyright and patent protection, which benefit people it likes.

The most obvious reason that France’s employment rates have not returned to pre-recession levels is the austerity demanded by Germany, which it is able to impose on France through its control of the euro. There is little reason to believe that if France were able to spend another 1–2 percent of its GDP on infrastructure, training, and other forms of public investment, its economy and employment would not expand.

The Post is of course a big fan of austerity. Rather than acknowledging that a lack of demand is the main factor keeping workers from being employed, it would rather blame the workers for lacking the right skills.

The Washington Post has long pushed the view that a dollar (or euro) that is in the pocket of a middle-class person is a dollar that should be in the pockets of the rich. (They are okay with crumbs for the poor.) In keeping with this position, in its lead editorial today the Post complained about the “sclerotic statism” of the French economy. It then called for increasing employment, “through reforms of the labor code, not by protectionism or restriction of immigration.”

It is worth bringing a little bit of data to the fact free zone of the Washington Post opinion pages. France actually has consistently had a higher employment rate for its prime-age workers (ages 25 to 54) than the United States.

As can be seen, the employment rate for prime-age workers in France was roughly 2 percentage points higher in 2003. The gap expanded to almost 7 percentage points following the downturn, but it has in more recent years narrowed again to just under 2 percentage points.

France does have much lower employment rates among younger and older workers than the United States, but this is due to policy choices. College is largely free in France and students get stipends from the government. Therefore, many fewer young people work. France also makes it much easier for people to retire in their early sixties than in the United States, with largely free health care and earlier pensions. The merits of these policies can be debated, but they are not evidence of a sclerotic economy.

It is also not clear that the Washington Post’s desire to weaken protections for workers (euphemistically described as “reforms of the labor code”) will have a significant effect in reducing unemployment or raising employment. Extensive research has shown there is little relationship between worker protections and employment. It is also worth noting that the Post denounced protectionism in this editorial, but it is fine with protectionism in the form of ever longer and stronger copyright and patent protection, which benefit people it likes.

The most obvious reason that France’s employment rates have not returned to pre-recession levels is the austerity demanded by Germany, which it is able to impose on France through its control of the euro. There is little reason to believe that if France were able to spend another 1–2 percent of its GDP on infrastructure, training, and other forms of public investment, its economy and employment would not expand.

The Post is of course a big fan of austerity. Rather than acknowledging that a lack of demand is the main factor keeping workers from being employed, it would rather blame the workers for lacking the right skills.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión