Washington Post columnist Charles Lane is a devout proponent of the policy of selective protectionism. Under this policy, which is called “free trade” for marketing purposes, the wages of U.S. manufacturing workers and non-college educated workers more generally are pushed down by placing them in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world.

By contrast, highly paid professionals like doctors and dentists are able to achieve gains in wages by keeping in place the barriers that protect them from similar competition. In addition, drug companies, medical equipment companies, and software companies benefit from ever longer and stronger patent and copyright protection.

This selective protectionism is a key part of the upward redistribution of the last four decades. (Yes, this is the story of my book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer [it’s free].) Anyhow, Lane is apparently upset that Donald Trump and much of the public seem to be rejecting this policy of selective protectionism so he used the 100th anniversary of John Kennedy’s birth to enlist him in the cause.

As Lane tells it, John Kennedy proclaimed:

“Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do to make the rich even richer.”

Washington Post columnist Charles Lane is a devout proponent of the policy of selective protectionism. Under this policy, which is called “free trade” for marketing purposes, the wages of U.S. manufacturing workers and non-college educated workers more generally are pushed down by placing them in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world.

By contrast, highly paid professionals like doctors and dentists are able to achieve gains in wages by keeping in place the barriers that protect them from similar competition. In addition, drug companies, medical equipment companies, and software companies benefit from ever longer and stronger patent and copyright protection.

This selective protectionism is a key part of the upward redistribution of the last four decades. (Yes, this is the story of my book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer [it’s free].) Anyhow, Lane is apparently upset that Donald Trump and much of the public seem to be rejecting this policy of selective protectionism so he used the 100th anniversary of John Kennedy’s birth to enlist him in the cause.

As Lane tells it, John Kennedy proclaimed:

“Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do to make the rich even richer.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had an article reporting on the fact that President Trump’s hotels have not been consistently screening payments from foreign governments to donate to charities, as he had promised in order to comply with the constitutional ban on such payments. The article cites a document from the Trump Organization saying that it would be impractical to screen all their guests to determine which ones were representatives of foreign governments.

While this sort of screening may exceed the competency of the Trump Organization, there is an extremely simply route that would allow Mr. Trump to comply with the law. He can sell his assets and place them in a blind trust. This can quickly be done in a way that need not involve a rushed sale of assets.

It is understandable that Trump may not want to sell his business empire, but this is the sort of thing that we expect adults to think about before they take a job. If the business is so valuable to him, then he should not have run for president.

The Washington Post had an article reporting on the fact that President Trump’s hotels have not been consistently screening payments from foreign governments to donate to charities, as he had promised in order to comply with the constitutional ban on such payments. The article cites a document from the Trump Organization saying that it would be impractical to screen all their guests to determine which ones were representatives of foreign governments.

While this sort of screening may exceed the competency of the Trump Organization, there is an extremely simply route that would allow Mr. Trump to comply with the law. He can sell his assets and place them in a blind trust. This can quickly be done in a way that need not involve a rushed sale of assets.

It is understandable that Trump may not want to sell his business empire, but this is the sort of thing that we expect adults to think about before they take a job. If the business is so valuable to him, then he should not have run for president.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times ran a column by Maya MacGuineas, the president of the Peter Peterson-backed Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. The piece begins with the ominous announcement:

“President Trump entered office facing the worst ratio of debt to gross domestic product of any new president in American history except Harry Truman — an onerous 77 percent.”

It could have also begun with the announcement that the ratio of debt service (interest on the debt, net of payments from the Federal Reserve Board) to GDP is less than one percent. This contrasts with a ratio of almost 3.0 percent in the early and mid-1990s. Are you scared yet?

Actually, you should be. Folks like Ms. MacGuineas have pushed austerity policies in the United States and around the world for the last decade. These policies have prevented the government from spending the amount necessary to restore the economy to full employment. This has not only kept millions of people in the United States from having jobs, it has prevented tens of millions from getting pay increases by weakening their bargaining power.

Furthermore, the lower levels of output have an enduring impact on the economy. They are associated with less investment in public and private capital and less money spent on research and development. In addition, unemployed workers don’t gain the experience they would have otherwise. Many of the long-term unemployed drop out of the labor force and may end up never working again.

As a result of these effects, the Congressional Budget Office now estimates that the economy’s potential level of output for 2017 is 10 percent less than what it had projected for 2017 back in 2008 before the Great Recession really took hold. The loss in output due to this austerity tax is roughly $2 trillion a year. This is the reduction in wages and profit income as a result of the smaller size of the economy. That comes to $6,000 per person per year.

This is the burden that the Peter Peterson crew have imposed on our children and grandchildren due to their scare tactics on the deficits. (Hey, remember the Reinhart-Rogoff 90 percent debt to GDP cliff?) And fans of logic everywhere know that it will not matter one iota to our kids’ well-being if the government were to increase taxes on each of them by $6,000 or whether its austerity policies lead them to earn $6,000 less each year.

Unfortunately, because of the distribution of money and power in society, it is only the taxes that will draw attention. The fact that inept economic management needlessly caused us to sacrifice economic growth, and did so in a way that disproportionately hurt the poor and middle class, is considered rude to mention in polite company.

Instead, we get columns with meaningless figures about debt to GDP that are designed to scare people.

Addendum:

I somehow forget to mention the rents from government-granted patent and copyright monopolies. As I point out in Rigged, these come to close to $400 billion a year in the case of prescription drugs alone. This is the difference between the patent-protected price and the free market price. It is effectively a privately collected tax. If we add in the rents from medical equipment, software, and other items the figure could easily be twice as high. In other words, we are making our kids pay $400 billion to $800 billion a year to pay for the research and creative work that was done in the past.

Anyone seriously concerned about the burden we impose on our kids has to include this cost in their calculations. Otherwise, they just deserve to have their pronouncements treated with ridicule.

The New York Times ran a column by Maya MacGuineas, the president of the Peter Peterson-backed Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. The piece begins with the ominous announcement:

“President Trump entered office facing the worst ratio of debt to gross domestic product of any new president in American history except Harry Truman — an onerous 77 percent.”

It could have also begun with the announcement that the ratio of debt service (interest on the debt, net of payments from the Federal Reserve Board) to GDP is less than one percent. This contrasts with a ratio of almost 3.0 percent in the early and mid-1990s. Are you scared yet?

Actually, you should be. Folks like Ms. MacGuineas have pushed austerity policies in the United States and around the world for the last decade. These policies have prevented the government from spending the amount necessary to restore the economy to full employment. This has not only kept millions of people in the United States from having jobs, it has prevented tens of millions from getting pay increases by weakening their bargaining power.

Furthermore, the lower levels of output have an enduring impact on the economy. They are associated with less investment in public and private capital and less money spent on research and development. In addition, unemployed workers don’t gain the experience they would have otherwise. Many of the long-term unemployed drop out of the labor force and may end up never working again.

As a result of these effects, the Congressional Budget Office now estimates that the economy’s potential level of output for 2017 is 10 percent less than what it had projected for 2017 back in 2008 before the Great Recession really took hold. The loss in output due to this austerity tax is roughly $2 trillion a year. This is the reduction in wages and profit income as a result of the smaller size of the economy. That comes to $6,000 per person per year.

This is the burden that the Peter Peterson crew have imposed on our children and grandchildren due to their scare tactics on the deficits. (Hey, remember the Reinhart-Rogoff 90 percent debt to GDP cliff?) And fans of logic everywhere know that it will not matter one iota to our kids’ well-being if the government were to increase taxes on each of them by $6,000 or whether its austerity policies lead them to earn $6,000 less each year.

Unfortunately, because of the distribution of money and power in society, it is only the taxes that will draw attention. The fact that inept economic management needlessly caused us to sacrifice economic growth, and did so in a way that disproportionately hurt the poor and middle class, is considered rude to mention in polite company.

Instead, we get columns with meaningless figures about debt to GDP that are designed to scare people.

Addendum:

I somehow forget to mention the rents from government-granted patent and copyright monopolies. As I point out in Rigged, these come to close to $400 billion a year in the case of prescription drugs alone. This is the difference between the patent-protected price and the free market price. It is effectively a privately collected tax. If we add in the rents from medical equipment, software, and other items the figure could easily be twice as high. In other words, we are making our kids pay $400 billion to $800 billion a year to pay for the research and creative work that was done in the past.

Anyone seriously concerned about the burden we impose on our kids has to include this cost in their calculations. Otherwise, they just deserve to have their pronouncements treated with ridicule.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Nope, that is not what the Washington Post said, instead it insisted to readers that the opposite is the case. The first sentence of a front page article on the Trump administration’s infrastructure plans told readers:

“The Trump administration, determined to overhaul and modernize the nation’s infrastructure, is drafting plans to privatize some public assets such as airports, bridges, highway rest stops and other facilities, according to top officials and advisers.”

I guess this is another case where we are relying on the extraordinary mind-reading skills of reporters, since the rest of us would not know that the administration is pursuing privatization plans because it is “determined to overhaul and modernize the nation’s infrastructure,” as opposed to making the Trump family and people like them even richer. The evidence of past privatizations might suggest the opposite.

While the piece does note some of the past failures of privatization projects, the framing in the first sentence attributes good faith in its motives which there is zero reason to assume. It is certainly possible that the Trump administration is acting in what it perceives to be the public good but it is also entirely possible that it is trying to further enrich a small group of wealthy people at the expense of everyone else.

The Post has no basis for its assertion that Trump administration actually gives a damn about the public interest.

Nope, that is not what the Washington Post said, instead it insisted to readers that the opposite is the case. The first sentence of a front page article on the Trump administration’s infrastructure plans told readers:

“The Trump administration, determined to overhaul and modernize the nation’s infrastructure, is drafting plans to privatize some public assets such as airports, bridges, highway rest stops and other facilities, according to top officials and advisers.”

I guess this is another case where we are relying on the extraordinary mind-reading skills of reporters, since the rest of us would not know that the administration is pursuing privatization plans because it is “determined to overhaul and modernize the nation’s infrastructure,” as opposed to making the Trump family and people like them even richer. The evidence of past privatizations might suggest the opposite.

While the piece does note some of the past failures of privatization projects, the framing in the first sentence attributes good faith in its motives which there is zero reason to assume. It is certainly possible that the Trump administration is acting in what it perceives to be the public good but it is also entirely possible that it is trying to further enrich a small group of wealthy people at the expense of everyone else.

The Post has no basis for its assertion that Trump administration actually gives a damn about the public interest.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Paul Ryan won widespread applause from the Peter Peterson-types some years back for proposing a budget that would virtually eliminate the federal government by 2050, excepting Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and the military. According to the Congressional Budget Office’s analysis of the Ryan budget (done under Speaker Ryan’s supervision), spending on everything other than Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid would be reduced to 3.5 percent of GDP in 2050. With military spending likely running in the neighborhood of 3.0 percent of GDP, this left around 0.5 percent of GDP for federal spending on education, infrastructure, the Justice Department, research and development, national parks, and all the other things we think of the government as doing.

Well, Ryan now has some serious competition from Donald Trump. In his budget, he has these same categories of spending shrinking to 3.6 percent of GDP by 2027, down from 6.3 percent of GDP at present. While Ryan’s endpoint may be more impressive, it is important to remember that he has another 23 years to get there. According to CBO, in 2030 Ryan’s budget has 5.25 percent of GDP going to the same categories of spending, including the military. If we pull out 3.0 percent for the military (Ryan is more hawkish than Trump, who only spending 2.3 percent of GDP on the military in 2027) then Ryan would have 2.25 percent of GDP for this everything else category in 2030.

So we have Trump at 3.6 percent of GDP for the bulk of the federal government in 2027 compared to 2.3 percent in the same categories for Ryan in 2030. If we assume the same rate of decline in the years from 2027 t0 2030 as in the years 2017 to 2027, then Trump’s budget would be down to 2.8 percent of GDP by 2030. It looks like Ryan is still somewhat ahead of Trump in his plan to eliminate the federal government, but Trump can still hope to catch up.

Paul Ryan won widespread applause from the Peter Peterson-types some years back for proposing a budget that would virtually eliminate the federal government by 2050, excepting Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and the military. According to the Congressional Budget Office’s analysis of the Ryan budget (done under Speaker Ryan’s supervision), spending on everything other than Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid would be reduced to 3.5 percent of GDP in 2050. With military spending likely running in the neighborhood of 3.0 percent of GDP, this left around 0.5 percent of GDP for federal spending on education, infrastructure, the Justice Department, research and development, national parks, and all the other things we think of the government as doing.

Well, Ryan now has some serious competition from Donald Trump. In his budget, he has these same categories of spending shrinking to 3.6 percent of GDP by 2027, down from 6.3 percent of GDP at present. While Ryan’s endpoint may be more impressive, it is important to remember that he has another 23 years to get there. According to CBO, in 2030 Ryan’s budget has 5.25 percent of GDP going to the same categories of spending, including the military. If we pull out 3.0 percent for the military (Ryan is more hawkish than Trump, who only spending 2.3 percent of GDP on the military in 2027) then Ryan would have 2.25 percent of GDP for this everything else category in 2030.

So we have Trump at 3.6 percent of GDP for the bulk of the federal government in 2027 compared to 2.3 percent in the same categories for Ryan in 2030. If we assume the same rate of decline in the years from 2027 t0 2030 as in the years 2017 to 2027, then Trump’s budget would be down to 2.8 percent of GDP by 2030. It looks like Ryan is still somewhat ahead of Trump in his plan to eliminate the federal government, but Trump can still hope to catch up.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

If anyone thought that Republicans believed in local rule or protecting the public from criminals, the Texas legislature is working hard to correct this misunderstanding. It just passed a new law that prohibits Texas’ cities from imposing requirements on taxi services like Uber or Lyft.

The law was passed in response to a measure by Austin that required that drivers for Uber and other services undergo a background check that included fingerprints. Uber and Lyft claimed that they were too incompetent to administer the same sort of background checks as their competitors. After spending millions of dollars on a city-wide initiative, which they lost, the two companies chose to end service in the city rather than comply with the ordinance.

They then turned to lobbying the Texas legislature where their millions in lobbying fees paid off. The new law could also override a measure in Houston that requires these companies to service people with handicaps.

Anyhow, this action by the Republican-controlled legislature should make it clear that the core Republican principle is giving more money to those who have money. Anything else is secondary.

Correction:

I wrote this post in haste and likely gave the readers the impression that I thought people who had been convicted of felonies should not be able to drive cabs and should possible be denied other types of employment. I very much regret that. We have had far too many people, disproportionately people of color, go through our prison system. Most have enormous difficulty being employed after they have completed their sentence.

It is entirely reasonable that people convicted of crimes in the past would be allowed to drive Ubers or cabs, if it can be determined that they do not pose a danger to passengers. The key is the ability to do a proper background check of the person, which likely would include fingerprint checks, which was the issue with the Austin regulation.

I wrote the post because it is not plausible that the Texas legislature was motivated by a concern about the employment prospects of people who had been convicted of crimes. They were obviously responding to Uber’s high dollar lobbying campaign. I should have been more careful in writing this post, recognizing the difficulty that many convicted of crimes face in getting jobs.

If anyone thought that Republicans believed in local rule or protecting the public from criminals, the Texas legislature is working hard to correct this misunderstanding. It just passed a new law that prohibits Texas’ cities from imposing requirements on taxi services like Uber or Lyft.

The law was passed in response to a measure by Austin that required that drivers for Uber and other services undergo a background check that included fingerprints. Uber and Lyft claimed that they were too incompetent to administer the same sort of background checks as their competitors. After spending millions of dollars on a city-wide initiative, which they lost, the two companies chose to end service in the city rather than comply with the ordinance.

They then turned to lobbying the Texas legislature where their millions in lobbying fees paid off. The new law could also override a measure in Houston that requires these companies to service people with handicaps.

Anyhow, this action by the Republican-controlled legislature should make it clear that the core Republican principle is giving more money to those who have money. Anything else is secondary.

Correction:

I wrote this post in haste and likely gave the readers the impression that I thought people who had been convicted of felonies should not be able to drive cabs and should possible be denied other types of employment. I very much regret that. We have had far too many people, disproportionately people of color, go through our prison system. Most have enormous difficulty being employed after they have completed their sentence.

It is entirely reasonable that people convicted of crimes in the past would be allowed to drive Ubers or cabs, if it can be determined that they do not pose a danger to passengers. The key is the ability to do a proper background check of the person, which likely would include fingerprint checks, which was the issue with the Austin regulation.

I wrote the post because it is not plausible that the Texas legislature was motivated by a concern about the employment prospects of people who had been convicted of crimes. They were obviously responding to Uber’s high dollar lobbying campaign. I should have been more careful in writing this post, recognizing the difficulty that many convicted of crimes face in getting jobs.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes, it’s yet another example of the skills shortage. In the middle of his review of a new book by Mervyn King, the former head of the Bank of England, Steven Pearlstein tells readers:

“If you are like me, just thinking about the constant interplay among trade flows, investment flows, savings rates, exchange rates, inflation, interest rates and asset prices makes your head hurt. Perhaps that’s because it’s never exactly clear what is cause and what is effect, or whether the effect is up or down.”

For people whose head doesn’t hurt, the chains of causation are actually fairly clear. While Pearlstein tells readers that the United States and the other Anglo-Saxon countries are “saving too little,” in a context where other countries are propping up the dollars (as King claims and Pearlstein apparently agrees), causing us to run large trade deficits, we are saving too much.

The trade deficits the United States and other countries run as a result of having over-valued currencies lead to unemployment unless they are offset by large budget deficits. The budget deficits run in the years after the 2001 recession and 2008–2009 recession were insufficient to restore the economy to full employment. (We did eventually reach something close to full employment in 2006–2007 due to the construction and consumption demand generated by the housing bubble.)

Larger budgets would mean less national savings, although the increased borrowing associated with the deficit would be partially offset by the additional output in the economy, which would lead to more savings. It is also possible to get back to full employment by reducing labor supply through measures such as work sharing, mandated paid vacations, and other measures designed to shorten the average work year. This is how Germany managed to reduce its unemployment in the Great Recession, even though it had a sharper fall in output than the United States.

Pearlstein’s confusion on cause and effect also leads him to claim some sort of crisis is imminent, since at some point other countries are likely to stop propping up the dollar. There is no basis for this assertion. We actually have a clear precedent for this story of adjustment.

In the late 1980s, following the 1985 Plaza Accord, Japan, Germany, and our other major trading partners helped to engineer a sharp reduction in the value of the dollar, which caused our trade deficit to decline from a peak of more than 3.0 percent of GDP in 1986 to roughly 1.0 percent of GDP by 1989. The economy grew at a respectable pace throughout this period and there was no major uptick in inflation.

Yes, it’s yet another example of the skills shortage. In the middle of his review of a new book by Mervyn King, the former head of the Bank of England, Steven Pearlstein tells readers:

“If you are like me, just thinking about the constant interplay among trade flows, investment flows, savings rates, exchange rates, inflation, interest rates and asset prices makes your head hurt. Perhaps that’s because it’s never exactly clear what is cause and what is effect, or whether the effect is up or down.”

For people whose head doesn’t hurt, the chains of causation are actually fairly clear. While Pearlstein tells readers that the United States and the other Anglo-Saxon countries are “saving too little,” in a context where other countries are propping up the dollars (as King claims and Pearlstein apparently agrees), causing us to run large trade deficits, we are saving too much.

The trade deficits the United States and other countries run as a result of having over-valued currencies lead to unemployment unless they are offset by large budget deficits. The budget deficits run in the years after the 2001 recession and 2008–2009 recession were insufficient to restore the economy to full employment. (We did eventually reach something close to full employment in 2006–2007 due to the construction and consumption demand generated by the housing bubble.)

Larger budgets would mean less national savings, although the increased borrowing associated with the deficit would be partially offset by the additional output in the economy, which would lead to more savings. It is also possible to get back to full employment by reducing labor supply through measures such as work sharing, mandated paid vacations, and other measures designed to shorten the average work year. This is how Germany managed to reduce its unemployment in the Great Recession, even though it had a sharper fall in output than the United States.

Pearlstein’s confusion on cause and effect also leads him to claim some sort of crisis is imminent, since at some point other countries are likely to stop propping up the dollar. There is no basis for this assertion. We actually have a clear precedent for this story of adjustment.

In the late 1980s, following the 1985 Plaza Accord, Japan, Germany, and our other major trading partners helped to engineer a sharp reduction in the value of the dollar, which caused our trade deficit to decline from a peak of more than 3.0 percent of GDP in 1986 to roughly 1.0 percent of GDP by 1989. The economy grew at a respectable pace throughout this period and there was no major uptick in inflation.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

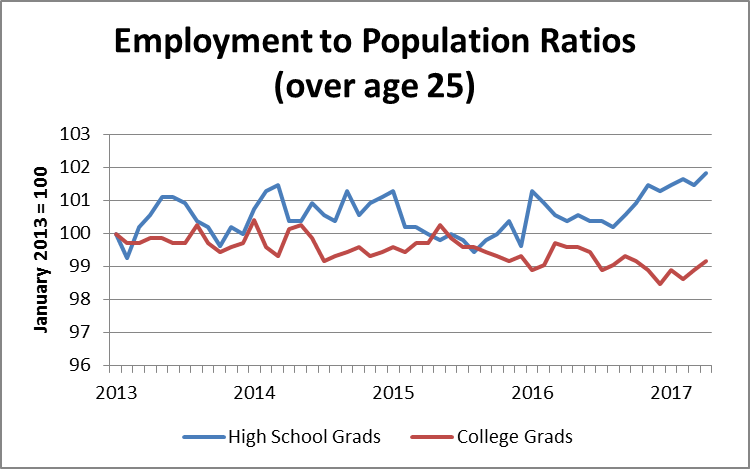

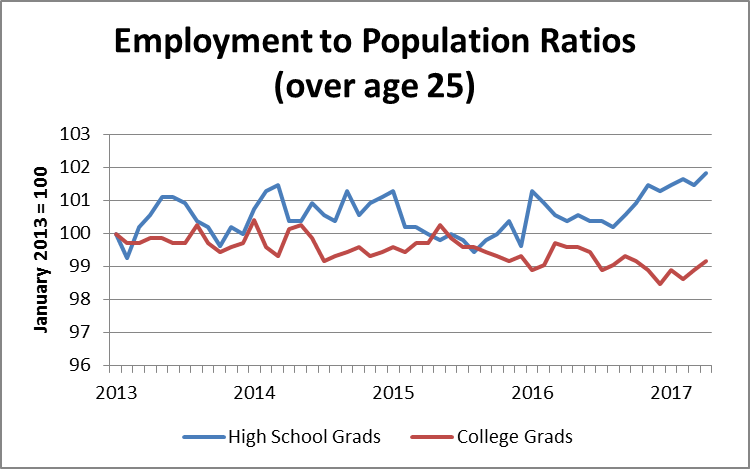

It is so annoying when the economy refuses to listen to what the economists say it should be doing. In this case, it seems to be ignoring the insistence that new jobs require more education and typically a college degree.

The problem is that in the last four years the employment-to-population ratio has actually been rising for people with just a high school degree while it is has fallen slightly for people with college degrees.

Since January of 2013, the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) for people with just a high school degree has risen by almost two percentage points while it has fallen by almost one percentage point for college grads. This certainly doesn’t fit the simple story of people needing more education for the jobs being created in today’s economy.

Obviously, there are other factors at play here, but the most obvious one, the retirement of the baby boom generation, should work the other way. The people who reached retirement age during the last four years were disproportionately less educated, which should depress the EPOP of workers with just high school degrees relative to college grads.

To be clear, people with college degrees are undoubtedly better off in today’s labor market than those with less education. Their overall employment is 72 percent, compared to just 55 percent for high school grads. And, they get paid much more when they do work. But at least by the EPOP measure, it does not appear that the labor market is being increasingly tilted in their favor as often claimed.

It is so annoying when the economy refuses to listen to what the economists say it should be doing. In this case, it seems to be ignoring the insistence that new jobs require more education and typically a college degree.

The problem is that in the last four years the employment-to-population ratio has actually been rising for people with just a high school degree while it is has fallen slightly for people with college degrees.

Since January of 2013, the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) for people with just a high school degree has risen by almost two percentage points while it has fallen by almost one percentage point for college grads. This certainly doesn’t fit the simple story of people needing more education for the jobs being created in today’s economy.

Obviously, there are other factors at play here, but the most obvious one, the retirement of the baby boom generation, should work the other way. The people who reached retirement age during the last four years were disproportionately less educated, which should depress the EPOP of workers with just high school degrees relative to college grads.

To be clear, people with college degrees are undoubtedly better off in today’s labor market than those with less education. Their overall employment is 72 percent, compared to just 55 percent for high school grads. And, they get paid much more when they do work. But at least by the EPOP measure, it does not appear that the labor market is being increasingly tilted in their favor as often claimed.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

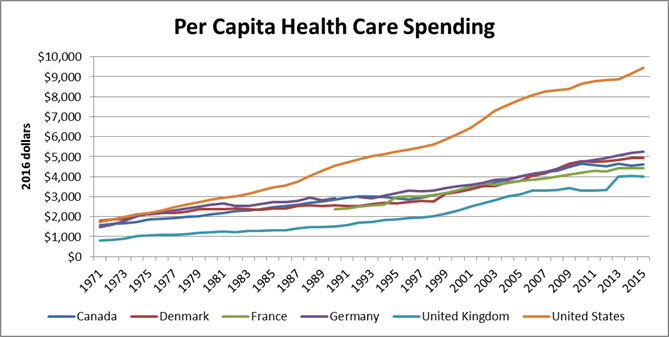

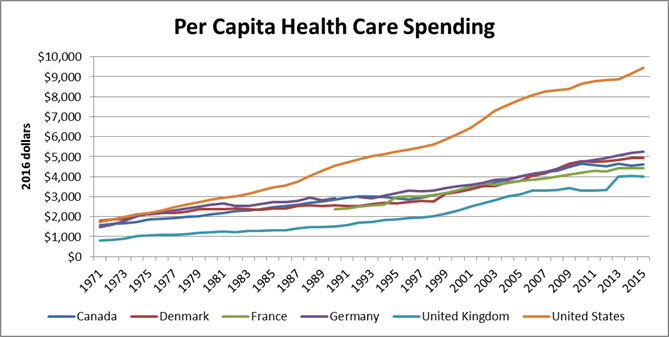

In his Washington Post column today George Will told readers that the problem of rising costs in the U.S. health care system is simply a case of Baumol’s disease. This refers to the problem identified by economist William Baumol (who recently died), that productivity in the service sector tends to rise less rapidly than productivity in the manufacturing sector. The implication is that if workers get paid the same in both sectors, then the cost of services will always rise relative to the cost of manufactured goods. Will tells us that this is the story of rapidly rising health care costs.

There are a couple of big problems with this story. First, it is not always the case that productivity in services rises less rapidly than productivity in manufacturing. ATMs have hugely increased the ability of banks to serve customers without tellers. Film developing became hugely more productive with digital cameras.

It is quite likely in the decades ahead that we will see innovations in technology that will lead to large increases in productivity in health care. For example, improvements in diagnostic technology will likely allow a skilled technician to diagnose illnesses with better accuracy than the best doctor. Similarly, robots will almost certainly be able to perform delicate surgeries with more precision than the best surgeon. In these and other areas of health care there is enormous potential for productivity gains, assuming that doctors and others who stand to lose don’t use their political power to block the technology.

This brings up the second point. While health care costs have risen everywhere, no other country pays anything close to what we do in the United States, even though they have comparable outcomes. The figure below shows per capita health care spending in the United States and five other wealthy countries since 1971. (The numbers shown are from the OECD and expressed in purchasing power parity. I converted them to 2016 dollars using the PCE deflator.)

As can be seen, health care costs have been rising everywhere, but nowhere have they risen anywhere near as rapidly as in the United States. At the start of this period in 1971 the United States didn’t even lead the pack in per capita spending, coming in slightly below Denmark. In 2015, health care costs in the U.S. were more than twice as high as in Denmark and France and almost 2.4 times as high as in the United Kingdom. Even if we compare costs with Germany, the second most expensive country in this group, the savings would still be almost $4,200 a year per person, or more than $1.3 trillion for the country as a whole.

The reason our health care costs have risen so much more rapidly than anywhere else is not Baumol’s disease. Health care is a service everywhere, not just in the United States. The difference stems from the fact that doctors, insurers, drug companies, and medical equipment makers are far more capable of controlling the political process in the United States than in these other countries. They use their political power to restrict competition and get government subsidies. As a result, these actors are able to secure massive rents that come out of the pockets of the rest of us.

It is understandable that columnists and newspapers that would like to protect these rents would try to tell the public that high-cost health care is just a fact of nature, but it is not true.

In his Washington Post column today George Will told readers that the problem of rising costs in the U.S. health care system is simply a case of Baumol’s disease. This refers to the problem identified by economist William Baumol (who recently died), that productivity in the service sector tends to rise less rapidly than productivity in the manufacturing sector. The implication is that if workers get paid the same in both sectors, then the cost of services will always rise relative to the cost of manufactured goods. Will tells us that this is the story of rapidly rising health care costs.

There are a couple of big problems with this story. First, it is not always the case that productivity in services rises less rapidly than productivity in manufacturing. ATMs have hugely increased the ability of banks to serve customers without tellers. Film developing became hugely more productive with digital cameras.

It is quite likely in the decades ahead that we will see innovations in technology that will lead to large increases in productivity in health care. For example, improvements in diagnostic technology will likely allow a skilled technician to diagnose illnesses with better accuracy than the best doctor. Similarly, robots will almost certainly be able to perform delicate surgeries with more precision than the best surgeon. In these and other areas of health care there is enormous potential for productivity gains, assuming that doctors and others who stand to lose don’t use their political power to block the technology.

This brings up the second point. While health care costs have risen everywhere, no other country pays anything close to what we do in the United States, even though they have comparable outcomes. The figure below shows per capita health care spending in the United States and five other wealthy countries since 1971. (The numbers shown are from the OECD and expressed in purchasing power parity. I converted them to 2016 dollars using the PCE deflator.)

As can be seen, health care costs have been rising everywhere, but nowhere have they risen anywhere near as rapidly as in the United States. At the start of this period in 1971 the United States didn’t even lead the pack in per capita spending, coming in slightly below Denmark. In 2015, health care costs in the U.S. were more than twice as high as in Denmark and France and almost 2.4 times as high as in the United Kingdom. Even if we compare costs with Germany, the second most expensive country in this group, the savings would still be almost $4,200 a year per person, or more than $1.3 trillion for the country as a whole.

The reason our health care costs have risen so much more rapidly than anywhere else is not Baumol’s disease. Health care is a service everywhere, not just in the United States. The difference stems from the fact that doctors, insurers, drug companies, and medical equipment makers are far more capable of controlling the political process in the United States than in these other countries. They use their political power to restrict competition and get government subsidies. As a result, these actors are able to secure massive rents that come out of the pockets of the rest of us.

It is understandable that columnists and newspapers that would like to protect these rents would try to tell the public that high-cost health care is just a fact of nature, but it is not true.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión