There is a widely held view among policy types that drug companies would act like total morons if they did research under a government contract as opposed to having the lure of a patent monopoly. Apparently, this is not true, since it seems that the French drug company Sanofi has developed an effective vaccine doing research that was funded by the U.S. Army. So the theory of knowledge holding that otherwise intelligent people become worthless hacks in the process of drug development if the government is the source of funding is apparently not true.

Of course, this is not entirely a clean test of the proposition since Sanofi will still be given exclusive rights to market the vaccine. Apparently, even when the government is paying for the research upfront and taking all the risk (if the vaccine doesn’t work, Sanofi has still been paid), drug companies still need monopolies, because hey, how could they survive in a free market?

If people in policy positions and economists were interested in free markets, they would be very upset by this story.

There is a widely held view among policy types that drug companies would act like total morons if they did research under a government contract as opposed to having the lure of a patent monopoly. Apparently, this is not true, since it seems that the French drug company Sanofi has developed an effective vaccine doing research that was funded by the U.S. Army. So the theory of knowledge holding that otherwise intelligent people become worthless hacks in the process of drug development if the government is the source of funding is apparently not true.

Of course, this is not entirely a clean test of the proposition since Sanofi will still be given exclusive rights to market the vaccine. Apparently, even when the government is paying for the research upfront and taking all the risk (if the vaccine doesn’t work, Sanofi has still been paid), drug companies still need monopolies, because hey, how could they survive in a free market?

If people in policy positions and economists were interested in free markets, they would be very upset by this story.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

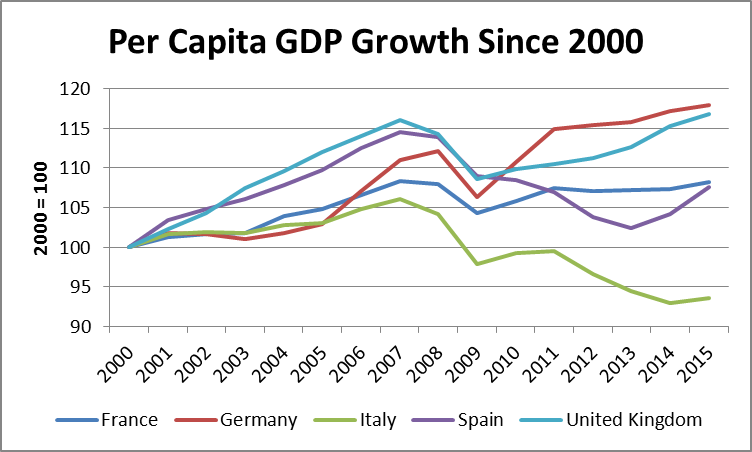

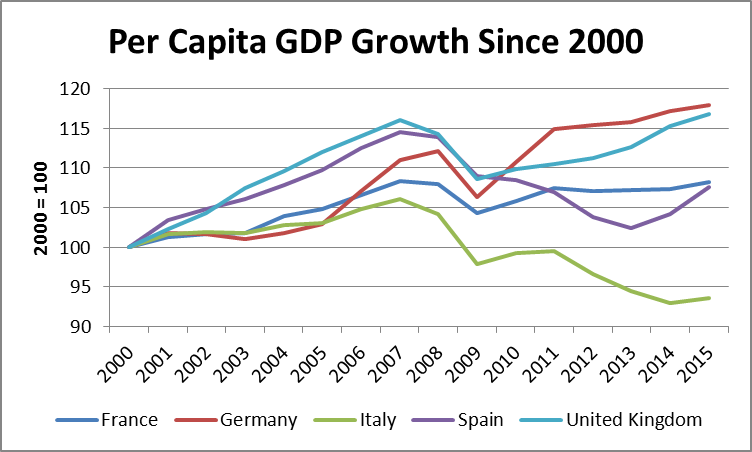

Okay, it’s Memorial Day weekend and maybe the regular crew is on vacation at the NYT, but come on, you don’t print GDP growth numbers without adjusting for inflation. The NYT committed this cardinal sin in a column by Simon Tilford telling readers that the United Kingdom actually has a pretty mediocre economy that is likely to perform even worse post-Brexit.

While I’m inclined to agree with the basic argument (with the qualification that there may be a dividend from sinking the financial sector), two of the graphs accompanying the piece likely left readers scratching their heads. The first showed per capita GDP growth since 2000 for Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and the UK. The moral was that the UK was not doing much better than France, which is supposed to have a moribund economy according to popular legend. The second showed a similar story with real wages.

The problem is that neither graph is adjusted for inflation. As a result, we see the shocking story that per capita GDP growth for both France and the UK have increased by more than 35 percent since 2000. Germany’s per capita GDP has increased by almost 50 percent.

That would be great news if true, but it’s not. Here’s the real picture.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

After adjusting for inflation, UK does a bit better relative to France, but 16 percent per capita GDP growth in 15 years is not much to brag about. (I suspect the picture looks less favorable to the UK if we adjust for changes in hours worked.) The story of Italy is especially striking. On a per capita basis, it is almost 7.0 percent poorer than it was at the turn of the century.

Okay, it’s Memorial Day weekend and maybe the regular crew is on vacation at the NYT, but come on, you don’t print GDP growth numbers without adjusting for inflation. The NYT committed this cardinal sin in a column by Simon Tilford telling readers that the United Kingdom actually has a pretty mediocre economy that is likely to perform even worse post-Brexit.

While I’m inclined to agree with the basic argument (with the qualification that there may be a dividend from sinking the financial sector), two of the graphs accompanying the piece likely left readers scratching their heads. The first showed per capita GDP growth since 2000 for Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and the UK. The moral was that the UK was not doing much better than France, which is supposed to have a moribund economy according to popular legend. The second showed a similar story with real wages.

The problem is that neither graph is adjusted for inflation. As a result, we see the shocking story that per capita GDP growth for both France and the UK have increased by more than 35 percent since 2000. Germany’s per capita GDP has increased by almost 50 percent.

That would be great news if true, but it’s not. Here’s the real picture.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

After adjusting for inflation, UK does a bit better relative to France, but 16 percent per capita GDP growth in 15 years is not much to brag about. (I suspect the picture looks less favorable to the UK if we adjust for changes in hours worked.) The story of Italy is especially striking. On a per capita basis, it is almost 7.0 percent poorer than it was at the turn of the century.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Washington Post columnist Steven Pearlstein urged people to be moderate in their criticisms of the Trump budget. In an obvious reference to plans to eliminate support for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the National Endowment for the Arts, he argues:

“I like Masterpiece Theatre and a Beethoven symphony as much as the next upper-middle-class professional, but I can see why some people might wonder why their tax dollars should subsidize my taste for British drama and classical music but not their preference for NASCAR and country western music.”

Actually, the Trump budget will not touch the major source of taxpayer subsidies for the sort of culture enjoyed primarily by higher income people. Last year the federal government gave $445 million to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (0.013 percent of total spending). It gave $150 million to the National Endowment for the Arts (0.004 percent of total spending).

By contrast, if a billionaire opts to give $1 billion to a local museum or orchestra, they will be able to write off roughly $400 million of this contribution from their taxes. The amount that taxpayers shell out through subsidizing these donations dwarfs the amount that they pay through direct federal support. The difference is that there is some public voice in where the money goes when the federal government appropriates it. The allocation of the tax subsidy is completely determined by the billionaires.

Washington Post columnist Steven Pearlstein urged people to be moderate in their criticisms of the Trump budget. In an obvious reference to plans to eliminate support for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the National Endowment for the Arts, he argues:

“I like Masterpiece Theatre and a Beethoven symphony as much as the next upper-middle-class professional, but I can see why some people might wonder why their tax dollars should subsidize my taste for British drama and classical music but not their preference for NASCAR and country western music.”

Actually, the Trump budget will not touch the major source of taxpayer subsidies for the sort of culture enjoyed primarily by higher income people. Last year the federal government gave $445 million to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (0.013 percent of total spending). It gave $150 million to the National Endowment for the Arts (0.004 percent of total spending).

By contrast, if a billionaire opts to give $1 billion to a local museum or orchestra, they will be able to write off roughly $400 million of this contribution from their taxes. The amount that taxpayers shell out through subsidizing these donations dwarfs the amount that they pay through direct federal support. The difference is that there is some public voice in where the money goes when the federal government appropriates it. The allocation of the tax subsidy is completely determined by the billionaires.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Matt O’Brien’s Wonkblog piece might have misled readers on Republicans views on the role of government. O’Brien argued that the reason that the Republicans have such a hard time designing a workable health care plan is:

“Republicans are philosophically opposed to redistribution, but health care is all about redistribution.”

This is completely untrue. Republicans push policies all the time that redistribute income upward. They are strong supporters of longer and stronger patent and copyright protection that make ordinary people pay more for everything from prescription drugs and medical equipment to software and video games. They routinely support measures that limit competition in the financial industry (for example, trying to ban state-run retirement plans) that will put more money in the pockets of the financial industry. And they support Federal Reserve Board policy that prevents people from getting jobs and pay increases, thereby redistributing income to employers and higher paid workers.

Republicans are just fine with having the government intervene in markets to redistribute income upward, they just don’t like policies that are designed to help the poor and middle class at the expense of the rich. It is wrong to imply, as O’Brien does, they have any other principles in these debates than giving as much money as possible to the rich. (Yes, this is the theme of my book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer [it’s free].)

Matt O’Brien’s Wonkblog piece might have misled readers on Republicans views on the role of government. O’Brien argued that the reason that the Republicans have such a hard time designing a workable health care plan is:

“Republicans are philosophically opposed to redistribution, but health care is all about redistribution.”

This is completely untrue. Republicans push policies all the time that redistribute income upward. They are strong supporters of longer and stronger patent and copyright protection that make ordinary people pay more for everything from prescription drugs and medical equipment to software and video games. They routinely support measures that limit competition in the financial industry (for example, trying to ban state-run retirement plans) that will put more money in the pockets of the financial industry. And they support Federal Reserve Board policy that prevents people from getting jobs and pay increases, thereby redistributing income to employers and higher paid workers.

Republicans are just fine with having the government intervene in markets to redistribute income upward, they just don’t like policies that are designed to help the poor and middle class at the expense of the rich. It is wrong to imply, as O’Brien does, they have any other principles in these debates than giving as much money as possible to the rich. (Yes, this is the theme of my book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer [it’s free].)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Neil Irwin examined recent patterns in wage growth in an NYT Upshot piece. Irwin noted the extraordinarily low 0.6 percent pace of productivity growth in recent years (where are the robots?) and argued that wage growth has actually been relatively fast. He then examines why productivity growth might be so slow.

One explanation he left out is that low wages make it possible to hire workers at low productivity jobs. If an employer only has to pay a worker the $7.25 federal minimum wage, then it can be profitable to hire the worker at jobs that increase revenue for the employer by just over $7.25 an hour. This can mean hiring someone to work the midnight shift at a convenience store or to work as a greeter at Walmart.

If the employer had to instead pay a worker $10 or $12 an hour, then many very low productivity jobs would no longer exist. This would raise the average level of productivity in the economy by eliminating the least productive jobs.

In this way, it is possible that the weakness of the labor market has been a factor in reducing productivity growth as workers have had no choice but to take low paying, low productivity jobs. If this is true, as the labor market tightens and wages start to grow more rapidly, we should see productivity increase more rapidly.

Neil Irwin examined recent patterns in wage growth in an NYT Upshot piece. Irwin noted the extraordinarily low 0.6 percent pace of productivity growth in recent years (where are the robots?) and argued that wage growth has actually been relatively fast. He then examines why productivity growth might be so slow.

One explanation he left out is that low wages make it possible to hire workers at low productivity jobs. If an employer only has to pay a worker the $7.25 federal minimum wage, then it can be profitable to hire the worker at jobs that increase revenue for the employer by just over $7.25 an hour. This can mean hiring someone to work the midnight shift at a convenience store or to work as a greeter at Walmart.

If the employer had to instead pay a worker $10 or $12 an hour, then many very low productivity jobs would no longer exist. This would raise the average level of productivity in the economy by eliminating the least productive jobs.

In this way, it is possible that the weakness of the labor market has been a factor in reducing productivity growth as workers have had no choice but to take low paying, low productivity jobs. If this is true, as the labor market tightens and wages start to grow more rapidly, we should see productivity increase more rapidly.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post printed a Reuters article that included a major mistake in economics. The piece is about the plotting of conservative politicians and business leaders trying to plan for the likelihood that their ally, President Michel Temer, will be indicted and removed from office for corruption. It told readers:

“Amid the political turmoil that comes just a year after his predecessor was impeached and removed from office, preserving Temer’s agenda of austerity reforms and pulling Brazil’s economy out of recession is more important than saving the leader himself, sources in three parties that are his main allies said.”

Actually, this statement is contradictory. The austerity is one of the main causes of the recession. If they want to pull the economy out of recession then they should be reversing the austerity. Hopefully, Mr. Temer’s allies understand this and it is just the Reuters’ reporter who is confused.

The next sentence added:

“Those measures range from reducing a gaping budget deficit through opening doors to foreign investors to weakening labor laws and tightening pensions.”

Readers may have been confused by the phrase “tightening pensions.” The normal English translation would have been “cutting pensions.” It is understandable that politicians who are trying to pursue policies that are unpopular may use euphemisms to conceal their agenda. It is not clear why Reuters or the Post would.

The Washington Post printed a Reuters article that included a major mistake in economics. The piece is about the plotting of conservative politicians and business leaders trying to plan for the likelihood that their ally, President Michel Temer, will be indicted and removed from office for corruption. It told readers:

“Amid the political turmoil that comes just a year after his predecessor was impeached and removed from office, preserving Temer’s agenda of austerity reforms and pulling Brazil’s economy out of recession is more important than saving the leader himself, sources in three parties that are his main allies said.”

Actually, this statement is contradictory. The austerity is one of the main causes of the recession. If they want to pull the economy out of recession then they should be reversing the austerity. Hopefully, Mr. Temer’s allies understand this and it is just the Reuters’ reporter who is confused.

The next sentence added:

“Those measures range from reducing a gaping budget deficit through opening doors to foreign investors to weakening labor laws and tightening pensions.”

Readers may have been confused by the phrase “tightening pensions.” The normal English translation would have been “cutting pensions.” It is understandable that politicians who are trying to pursue policies that are unpopular may use euphemisms to conceal their agenda. It is not clear why Reuters or the Post would.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s the question the board of directors of Charter should be asking, but I suspect they never do. The company scored first in the NYT’s annual compilation of CEO pay packages, coming in almost $30 million ahead of CBS, which is number 2. Of course, if the CEOs earned less than the other top people in the corporate hierarchy would likely get smaller paychecks as well. And, it might be harder for the presidents of universities, foundations, and non-profits to explain the need for seven figure salaries for their work.

It seems unlikely that directors ever push in a big way for lower pay for CEOs because they have almost no incentive to do so. More than 99 percent of the directors put up for re-election are approved by shareholders. This is because it is very difficult to organize among shareholders to unseat a director. (Think of the difficulty of unseating an incumbent member of Congress and multiply by about 100.)

As a result, there is no reason to raise unpleasant questions at board meetings. Even though they are supposed to serve shareholders, which means not paying one penny more than necessary to CEOs and top management for their performance (just as CEOs try to pay workers as little as possible), their incentive is to get along with top management. The result is the upward spiral in CEO pay that we have seen in the last four decades.

A big part of the problem is that asset managers (think Vanguard and Blackrock) routinely support management slates as they vote trillions (literally) of dollars worth of stock held by people in their 401(k)s and IRAs. These asset managers care more about staying on good terms with top management than making sure they aren’t overpaid. This creates a structure where ridiculously rich CEOs, who are usually big celebrants of the market, are effectively shielded themselves from market discipline. Isn’t that the way markets are supposed to work?

That’s the question the board of directors of Charter should be asking, but I suspect they never do. The company scored first in the NYT’s annual compilation of CEO pay packages, coming in almost $30 million ahead of CBS, which is number 2. Of course, if the CEOs earned less than the other top people in the corporate hierarchy would likely get smaller paychecks as well. And, it might be harder for the presidents of universities, foundations, and non-profits to explain the need for seven figure salaries for their work.

It seems unlikely that directors ever push in a big way for lower pay for CEOs because they have almost no incentive to do so. More than 99 percent of the directors put up for re-election are approved by shareholders. This is because it is very difficult to organize among shareholders to unseat a director. (Think of the difficulty of unseating an incumbent member of Congress and multiply by about 100.)

As a result, there is no reason to raise unpleasant questions at board meetings. Even though they are supposed to serve shareholders, which means not paying one penny more than necessary to CEOs and top management for their performance (just as CEOs try to pay workers as little as possible), their incentive is to get along with top management. The result is the upward spiral in CEO pay that we have seen in the last four decades.

A big part of the problem is that asset managers (think Vanguard and Blackrock) routinely support management slates as they vote trillions (literally) of dollars worth of stock held by people in their 401(k)s and IRAs. These asset managers care more about staying on good terms with top management than making sure they aren’t overpaid. This creates a structure where ridiculously rich CEOs, who are usually big celebrants of the market, are effectively shielded themselves from market discipline. Isn’t that the way markets are supposed to work?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Ever since the Trump administration released its budget on Tuesday, economists (including me) have been ridiculing its assumption that we will see an average annual growth rate of 3.0 percent over the next decade. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects an average growth rate of just under 1.9 percent for this period. This projection assumes slow labor force growth, as the baby boom cohort retires, and a continuation of the weak productivity growth we have seen over the last decade.

The Trump administration’s 3.0 percent growth number presumably assumes that productivity growth will rebound to something like the 3.0 percent growth rate we saw in the long Golden Age from 1947 to 1973 and again from 1995 to 2005. It seems that Mark Zuckerberg agrees with the Trump administration’s assessment since, according to the Washington Post, he warned of massive job loss due to technology in the years ahead and the need to have something like a universal basic income to ensure that people have enough money to survive.

If we continue to see the rates of productivity growth experienced in recent years and projected going forward by CBO, we will be seeing a labor shortage, not a shortage of jobs. So Mr. Zuckerberg, along with the Trump administration, has a very different view of the future than most of the economics profession (which doesn’t mean they are wrong).

Ever since the Trump administration released its budget on Tuesday, economists (including me) have been ridiculing its assumption that we will see an average annual growth rate of 3.0 percent over the next decade. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects an average growth rate of just under 1.9 percent for this period. This projection assumes slow labor force growth, as the baby boom cohort retires, and a continuation of the weak productivity growth we have seen over the last decade.

The Trump administration’s 3.0 percent growth number presumably assumes that productivity growth will rebound to something like the 3.0 percent growth rate we saw in the long Golden Age from 1947 to 1973 and again from 1995 to 2005. It seems that Mark Zuckerberg agrees with the Trump administration’s assessment since, according to the Washington Post, he warned of massive job loss due to technology in the years ahead and the need to have something like a universal basic income to ensure that people have enough money to survive.

If we continue to see the rates of productivity growth experienced in recent years and projected going forward by CBO, we will be seeing a labor shortage, not a shortage of jobs. So Mr. Zuckerberg, along with the Trump administration, has a very different view of the future than most of the economics profession (which doesn’t mean they are wrong).

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión