One of the largely overlooked implications of Friday’s weak job report is that it likely means that we will see a strong rebound in productivity growth for the second quarter. GDP growth is likely to bounce back from the first quarter’s weak 1.2 percent number, most likely coming in between 3.0 percent to 4.0 percent. With the rate of growth of hours worked likely less than 1.0 percent, we will be looking at productivity growth in the 2.0 percent to 3.0 percent range for the quarter.

Here are three quick thoughts:

1) Quarterly productivity data are hugely erratic, so most likely a rebound in a single quarter means nothing. It is entirely possible that the third quarter will put us back on our weak 1.0 percent productivity growth path.

2) I am betting that productivity growth will pick up as the labor market tightens further (or perhaps I should say “if” the labor market tightens further), as workers move from low-paying, low-productivity jobs (e.g. greeters at Walmart and the midnight shift at a convenience store) into higher paying, high-productivity jobs.

3) If productivity growth does pick up, it will be good for workers. We had 3.0 percent annual productivity growth from 1947 to 1973 and again from 1995 to 2005. In the first period, we had low unemployment and broadly shared wage gains. The same was true in the years from 1996 to 2001, until the collapse of the stock bubble threw us into a recession.

Strong productivity growth coupled with sound economic policy (e.g. the Fed not raising interest rates to keep people from getting jobs) creates the basis for rapidly improving standards of living. We need not worry about it leading to mass unemployment if the folks in charge of economic policy have a clue.

One of the largely overlooked implications of Friday’s weak job report is that it likely means that we will see a strong rebound in productivity growth for the second quarter. GDP growth is likely to bounce back from the first quarter’s weak 1.2 percent number, most likely coming in between 3.0 percent to 4.0 percent. With the rate of growth of hours worked likely less than 1.0 percent, we will be looking at productivity growth in the 2.0 percent to 3.0 percent range for the quarter.

Here are three quick thoughts:

1) Quarterly productivity data are hugely erratic, so most likely a rebound in a single quarter means nothing. It is entirely possible that the third quarter will put us back on our weak 1.0 percent productivity growth path.

2) I am betting that productivity growth will pick up as the labor market tightens further (or perhaps I should say “if” the labor market tightens further), as workers move from low-paying, low-productivity jobs (e.g. greeters at Walmart and the midnight shift at a convenience store) into higher paying, high-productivity jobs.

3) If productivity growth does pick up, it will be good for workers. We had 3.0 percent annual productivity growth from 1947 to 1973 and again from 1995 to 2005. In the first period, we had low unemployment and broadly shared wage gains. The same was true in the years from 1996 to 2001, until the collapse of the stock bubble threw us into a recession.

Strong productivity growth coupled with sound economic policy (e.g. the Fed not raising interest rates to keep people from getting jobs) creates the basis for rapidly improving standards of living. We need not worry about it leading to mass unemployment if the folks in charge of economic policy have a clue.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Many folks might have thought Donald Trump had abandoned his pledge about “draining the swamp” when he began filling his administration with Goldman Sachs alums and other Wall Street-types and reversed all the ethics rules put in place for the last five decades to prevent corruption. But the Washington Post tells us this is not true.

According to the Washington Post “draining the swamp” just meant firing government workers. So apparently if Wall Streeters and rich folks (including Trump family and friends) rip the taxpayers off for millions and billions in corrupt deals, it is okay as long as he fires government employees making five-figure salaries or maybe in a few cases, six-figure salaries.

So, Trump voters are apparently cool with being ripped off to put more money in the pockets of really rich people. They only get upset when their tax dollars are used to provide middle-income jobs for people doing things like cleaning up the environment or keeping our national parks in good shape. It’s good we have the Washington Post to tell us this.

Many folks might have thought Donald Trump had abandoned his pledge about “draining the swamp” when he began filling his administration with Goldman Sachs alums and other Wall Street-types and reversed all the ethics rules put in place for the last five decades to prevent corruption. But the Washington Post tells us this is not true.

According to the Washington Post “draining the swamp” just meant firing government workers. So apparently if Wall Streeters and rich folks (including Trump family and friends) rip the taxpayers off for millions and billions in corrupt deals, it is okay as long as he fires government employees making five-figure salaries or maybe in a few cases, six-figure salaries.

So, Trump voters are apparently cool with being ripped off to put more money in the pockets of really rich people. They only get upset when their tax dollars are used to provide middle-income jobs for people doing things like cleaning up the environment or keeping our national parks in good shape. It’s good we have the Washington Post to tell us this.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an article on Yahoo CEO’s $239 million payout for her five years as CEO of Yahoo. The article says that from the standpoint of shareholders, since the value of the company’s stock tripled, she earned her pay. This assessment is extremely misleading. It would be like saying that a firefighter getting paid $10 million earned her pay, because she got three people out of a burning house.

The question is not just the return to the shareholders, but the return compared to what they would have gotten had the next person in line been CEO. As the piece points out, the vast majority (perhaps all) of the gains to shareholders were due to the increase in the value of its stock holdings in Alibaba Group and Yahoo Japan. Ms. Mayer had virtually nothing to do with the rise in value of these holdings, although there were some legal issues that needed to be resolved to allow Yahoo shareholders to reap these gains.

While the resolution of these issues was important to shareholders, lawyers usually are not paid $48 million a year. And of course, Yahoo did actually have to pay lawyers to resolve these issues in any case.

As far as turning around Yahoo’s core business, the piece concludes that Mayer failed, but it was likely impossible in any case. While this assessment may be accurate, it doesn’t make sense from the shareholder’s standpoint to pay someone $239 million to do something that is impossible.

It actually would have been possible to structure a contract for a CEO that based their pay on the rise in Yahoo’s stock value net of its holdings in Alibaba Group and Yahoo Japan. (The contract could have even included a performance bonus of $5 to $10 million for overseeing the resolution of the legal issues with these holdings — pretty good pay for very part-time work.) Such a contract would almost certainly have left Ms. Mayer with a much smaller paycheck and Yahoo shareholders with more money.

As it is, shareholders effectively gave up roughly 0.4 percent of the value of the company to cover her pay over the last five years. This can be thought of as the CEO tax.

The NYT had an article on Yahoo CEO’s $239 million payout for her five years as CEO of Yahoo. The article says that from the standpoint of shareholders, since the value of the company’s stock tripled, she earned her pay. This assessment is extremely misleading. It would be like saying that a firefighter getting paid $10 million earned her pay, because she got three people out of a burning house.

The question is not just the return to the shareholders, but the return compared to what they would have gotten had the next person in line been CEO. As the piece points out, the vast majority (perhaps all) of the gains to shareholders were due to the increase in the value of its stock holdings in Alibaba Group and Yahoo Japan. Ms. Mayer had virtually nothing to do with the rise in value of these holdings, although there were some legal issues that needed to be resolved to allow Yahoo shareholders to reap these gains.

While the resolution of these issues was important to shareholders, lawyers usually are not paid $48 million a year. And of course, Yahoo did actually have to pay lawyers to resolve these issues in any case.

As far as turning around Yahoo’s core business, the piece concludes that Mayer failed, but it was likely impossible in any case. While this assessment may be accurate, it doesn’t make sense from the shareholder’s standpoint to pay someone $239 million to do something that is impossible.

It actually would have been possible to structure a contract for a CEO that based their pay on the rise in Yahoo’s stock value net of its holdings in Alibaba Group and Yahoo Japan. (The contract could have even included a performance bonus of $5 to $10 million for overseeing the resolution of the legal issues with these holdings — pretty good pay for very part-time work.) Such a contract would almost certainly have left Ms. Mayer with a much smaller paycheck and Yahoo shareholders with more money.

As it is, shareholders effectively gave up roughly 0.4 percent of the value of the company to cover her pay over the last five years. This can be thought of as the CEO tax.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT rightly criticized Donald Trump’s decision to pull the U.S. out of the Paris climate agreement, but part of its criticism is not right. It dismissed the idea that reducing greenhouse gas emissions would lead to job loss as “nonsense” that comes from “industry-friendly sources.” While the claim that reducing greenhouse gas emissions will lead to job loss may be nonsense, it is, in fact, the result that comes from standard economic models that are used all the time to project the impact of regulation policy, tax policy, health care, and trade policy.

These models are all full employment models, which means that everyone who wants to work at the market wage for their skills has a job. The way that reducing greenhouse gases reduces employment is by reducing the real wage. For example, if gas and electricity cost more, and wages have not risen to account for this increase, the real wage will be less. In these models, at a lower real wage fewer people will decide to work.

So, if complying with our Paris commitments causes the real wage to be 1.0 percent lower, then this may lead 0.5 percent fewer people to want to work, which translates into roughly 800,000 fewer people working. (These numbers are hypothetical, not taken from actual models.) So when Trump is citing models showing job loss associated with reducing greenhouse gas emissions, he is actually relying on mainstream economics (there is still a considerable range in this modeling, as some is almost deliberately dishonest).

There is one other point worth making on this topic. The military spending that Trump is so fond of also kills jobs in these models. Pre-Iraq War, we were on a path to be spending around 2.0 percent of GDP on the military. Instead, we’re looking at 3.3 percent now. A decade ago, CEPR contracted with Global Insight, one of the main econometric consulting firms, to project the impact of a sustained increase of 1.0 percentage point of GDP increase in military spending. It cost 700,000 jobs after two decades, mostly in construction and manufacturing.

In short, people may well want to reject the projections from these models — their track records have been pretty bad — but Trump is not just making this stuff up. And, the same sorts of models are widely used in other contexts (can you say “Trans-Pacific Partnership?”).

The NYT rightly criticized Donald Trump’s decision to pull the U.S. out of the Paris climate agreement, but part of its criticism is not right. It dismissed the idea that reducing greenhouse gas emissions would lead to job loss as “nonsense” that comes from “industry-friendly sources.” While the claim that reducing greenhouse gas emissions will lead to job loss may be nonsense, it is, in fact, the result that comes from standard economic models that are used all the time to project the impact of regulation policy, tax policy, health care, and trade policy.

These models are all full employment models, which means that everyone who wants to work at the market wage for their skills has a job. The way that reducing greenhouse gases reduces employment is by reducing the real wage. For example, if gas and electricity cost more, and wages have not risen to account for this increase, the real wage will be less. In these models, at a lower real wage fewer people will decide to work.

So, if complying with our Paris commitments causes the real wage to be 1.0 percent lower, then this may lead 0.5 percent fewer people to want to work, which translates into roughly 800,000 fewer people working. (These numbers are hypothetical, not taken from actual models.) So when Trump is citing models showing job loss associated with reducing greenhouse gas emissions, he is actually relying on mainstream economics (there is still a considerable range in this modeling, as some is almost deliberately dishonest).

There is one other point worth making on this topic. The military spending that Trump is so fond of also kills jobs in these models. Pre-Iraq War, we were on a path to be spending around 2.0 percent of GDP on the military. Instead, we’re looking at 3.3 percent now. A decade ago, CEPR contracted with Global Insight, one of the main econometric consulting firms, to project the impact of a sustained increase of 1.0 percentage point of GDP increase in military spending. It cost 700,000 jobs after two decades, mostly in construction and manufacturing.

In short, people may well want to reject the projections from these models — their track records have been pretty bad — but Trump is not just making this stuff up. And, the same sorts of models are widely used in other contexts (can you say “Trans-Pacific Partnership?”).

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s the question that Neil Irwin poses in his Upshot piece. He points to the drop in the unemployment rate to 4.3 percent, coupled with a drop in the labor force participation rate, and the weak job growth of the last three months. The argument is that these factors taken together could mean that there just are not that many more people interested in working.

This is a possibility, but there are some important data points pointing in the opposite direction. First, it is worth noting that the biggest drop in the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) occurred among women between the ages of 25 to 34. Their EPOP fell by 0.9 percentage points in May, from 72.3 percent to 71.4 percent. This is not a group that anyone expects to be dropping out of the labor force in large numbers. This looks like a fluke, which indicates the decline in EPOP reported for May may just be due to measurement error rather than something that actually exists in the world. (These data are erratic, so a movement like this is not uncommon.)

In terms of factors pointing the other way, wage growth actually appears to be slowing, with the year-over-year rate of increase in the hourly wage dropping to 2.5 percent compared with 2.7 percent earlier in the year. If we take the average of the last three months compared with the average of the prior three months, the annual rate is just 2.2 percent. We don’t expect wage growth to be slowing as the labor market gets tighter.

Similarly, the percentage of unemployment due to people voluntarily quitting their jobs is relatively low at 11.7 percent. This is below the pre-recession levels, which often exceeded 12.0 percent and far below the peaks hit in 2000, which got above 15 percent. Workers still seem reluctant to leave a job if they don’t have a new job lined up.

There also is no increase in the length of the workweek. At 34.4 hours the average workweek is 0.1 hour shorter than its duration two years ago. We would expect employers to try to be getting more hours out of each worker if they were having trouble finding new workers.

In short, while 4.3 percent is a relatively low unemployment rate (and below most economists’ estimates of full employment) there are important ways in which the labor market does not look like one at full employment. Hopefully, the Federal Reserve Board will give us the opportunity to learn the answer to this question.

That’s the question that Neil Irwin poses in his Upshot piece. He points to the drop in the unemployment rate to 4.3 percent, coupled with a drop in the labor force participation rate, and the weak job growth of the last three months. The argument is that these factors taken together could mean that there just are not that many more people interested in working.

This is a possibility, but there are some important data points pointing in the opposite direction. First, it is worth noting that the biggest drop in the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) occurred among women between the ages of 25 to 34. Their EPOP fell by 0.9 percentage points in May, from 72.3 percent to 71.4 percent. This is not a group that anyone expects to be dropping out of the labor force in large numbers. This looks like a fluke, which indicates the decline in EPOP reported for May may just be due to measurement error rather than something that actually exists in the world. (These data are erratic, so a movement like this is not uncommon.)

In terms of factors pointing the other way, wage growth actually appears to be slowing, with the year-over-year rate of increase in the hourly wage dropping to 2.5 percent compared with 2.7 percent earlier in the year. If we take the average of the last three months compared with the average of the prior three months, the annual rate is just 2.2 percent. We don’t expect wage growth to be slowing as the labor market gets tighter.

Similarly, the percentage of unemployment due to people voluntarily quitting their jobs is relatively low at 11.7 percent. This is below the pre-recession levels, which often exceeded 12.0 percent and far below the peaks hit in 2000, which got above 15 percent. Workers still seem reluctant to leave a job if they don’t have a new job lined up.

There also is no increase in the length of the workweek. At 34.4 hours the average workweek is 0.1 hour shorter than its duration two years ago. We would expect employers to try to be getting more hours out of each worker if they were having trouble finding new workers.

In short, while 4.3 percent is a relatively low unemployment rate (and below most economists’ estimates of full employment) there are important ways in which the labor market does not look like one at full employment. Hopefully, the Federal Reserve Board will give us the opportunity to learn the answer to this question.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post shamelessly uses both its news and opinion pages to push trade agreements. It famously even lied about Mexico’s GDP growth to tout the benefits of NAFTA, absurdly claiming it had quadrupled between 1987 and 2007 (the actual figure was 83 percent, according to the International Monetary Fund).

Given this background, it’s not surprising to see a piece that bemoaned the fact that Vietnam will not be able to get the large gains from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) projected for it in several models:

“Economists say Vietnam would have been one of the biggest winners of the deal. A 2016 study by the Peterson Institute of International Economics found that the Obama-era trade deal would have increased Vietnam’s gross domestic product by 8.1 percent by 2030, the most of any country in the deal, and expanded its exports by nearly a third. Economists expected the deal to expand access to foreign markets for Vietnamese producers of apparel, footwear and seafood, as well as stimulate economic reforms within the country.”

While many readers may see the rejection of the TPP by Trump (and likely Congress as well) as a serious misfortune for Vietnam, the good news is that the vast majority of the projected gains for Vietnam came from the reduction or removal of its own tariffs. This is something that the country can, in principle, do tomorrow if it wants those big 8.1 percent gains promised by the model cited.

Furthermore, Vietnam will not have to pay the higher prices for drugs and other items subject to longer and stronger patent and related protections as a result of the TPP. The model cited by the Post forgot to include the impact of the increase in these protections on economic growth. While most of the tariffs being reduced as a result of the TPP were already low, patent and copyright protections often raise the price of the protected items by several thousand percent above the free market price.

The other point worth mentioning is that the computable general equilibrium (CGE) models, like the one used to give this projection of gains for Vietnam from the TPP, have a horrible track record. In the case of the U.S. trade deal with Korea, the version of this model used by the United States International Trade Commission not only failed to predict the explosion in the U.S. trade deficit with Korea which followed the implementation of the deal, its prediction of the industries that would gain or lose from the pact had basically zero correlation with what actually happened.

In other words, there is little reason for Vietnam to spend time worrying about the projections from the CGE models showing it suffered as a result of the TPP’s demise. Of course, the models can be useful for advancing a political agenda.

The Washington Post shamelessly uses both its news and opinion pages to push trade agreements. It famously even lied about Mexico’s GDP growth to tout the benefits of NAFTA, absurdly claiming it had quadrupled between 1987 and 2007 (the actual figure was 83 percent, according to the International Monetary Fund).

Given this background, it’s not surprising to see a piece that bemoaned the fact that Vietnam will not be able to get the large gains from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) projected for it in several models:

“Economists say Vietnam would have been one of the biggest winners of the deal. A 2016 study by the Peterson Institute of International Economics found that the Obama-era trade deal would have increased Vietnam’s gross domestic product by 8.1 percent by 2030, the most of any country in the deal, and expanded its exports by nearly a third. Economists expected the deal to expand access to foreign markets for Vietnamese producers of apparel, footwear and seafood, as well as stimulate economic reforms within the country.”

While many readers may see the rejection of the TPP by Trump (and likely Congress as well) as a serious misfortune for Vietnam, the good news is that the vast majority of the projected gains for Vietnam came from the reduction or removal of its own tariffs. This is something that the country can, in principle, do tomorrow if it wants those big 8.1 percent gains promised by the model cited.

Furthermore, Vietnam will not have to pay the higher prices for drugs and other items subject to longer and stronger patent and related protections as a result of the TPP. The model cited by the Post forgot to include the impact of the increase in these protections on economic growth. While most of the tariffs being reduced as a result of the TPP were already low, patent and copyright protections often raise the price of the protected items by several thousand percent above the free market price.

The other point worth mentioning is that the computable general equilibrium (CGE) models, like the one used to give this projection of gains for Vietnam from the TPP, have a horrible track record. In the case of the U.S. trade deal with Korea, the version of this model used by the United States International Trade Commission not only failed to predict the explosion in the U.S. trade deficit with Korea which followed the implementation of the deal, its prediction of the industries that would gain or lose from the pact had basically zero correlation with what actually happened.

In other words, there is little reason for Vietnam to spend time worrying about the projections from the CGE models showing it suffered as a result of the TPP’s demise. Of course, the models can be useful for advancing a political agenda.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

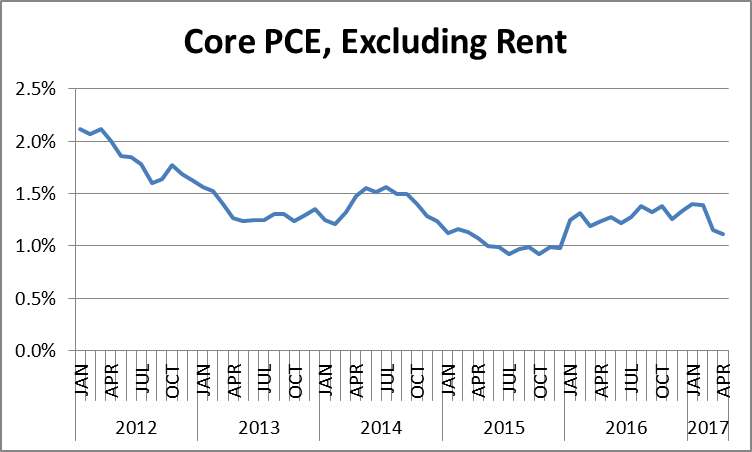

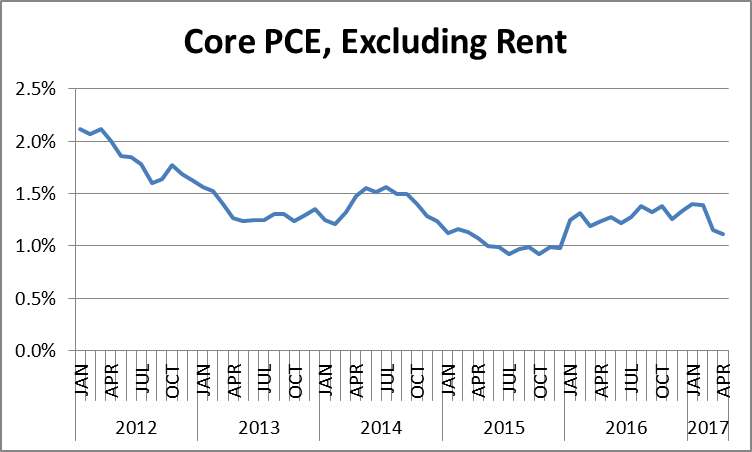

Housing rent has been outpacing the overall rate of inflation in recent years. This is worth noting both because it is a large portion of the consumption basket and rents do not tend to follow other prices. Rent is primarily a function of the shortage of available units. It does not respond in any immediate way to wage pressures, like other components in the consumption basket. Rental inflation will also not be slowed by higher interest rates. In fact, by reducing construction, higher interest rates may further tighten the supply of housing, leading to higher rental inflation.

If we look at the core personal consumption expenditure deflator excluding rent, it is both well below the Fed’s 2.0 percent target and, if anything, is trending lower over the last few years.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

This raises the question millions are asking: why is the Fed raising interest rates? We know this keeps people from getting jobs and workers, especially those at the bottom of the wage distribution, from getting pay increases. With no problems with inflation on the horizon, this looks like lots of pain for no obvious gain.

Note: An earlier version had the months improperly labeled.

Housing rent has been outpacing the overall rate of inflation in recent years. This is worth noting both because it is a large portion of the consumption basket and rents do not tend to follow other prices. Rent is primarily a function of the shortage of available units. It does not respond in any immediate way to wage pressures, like other components in the consumption basket. Rental inflation will also not be slowed by higher interest rates. In fact, by reducing construction, higher interest rates may further tighten the supply of housing, leading to higher rental inflation.

If we look at the core personal consumption expenditure deflator excluding rent, it is both well below the Fed’s 2.0 percent target and, if anything, is trending lower over the last few years.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

This raises the question millions are asking: why is the Fed raising interest rates? We know this keeps people from getting jobs and workers, especially those at the bottom of the wage distribution, from getting pay increases. With no problems with inflation on the horizon, this looks like lots of pain for no obvious gain.

Note: An earlier version had the months improperly labeled.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Using arithmetic in economic policy debates is always dangerous, but that would seem to be the implication of the NYT’s designation of Germany’s $64.8 billion trade surplus with the United States as “mammoth.” Since China’s $347.0 billion trade surplus was more than five times as large, it would seem that China’s surplus has to be five times massive. It usually is not talked about that way in the NYT and elsewhere.

Remarkably, the piece never focused on the real explanation for Germany’s large trade surplus. It insists on running budget surpluses, even though there continues to be widespread unemployment throughout the euro zone. This policy is far more harmful to the other euro zone countries than the United States.

If Germany ran budget deficits it would directly pull in more imports from its euro zone partners (and the United States), thereby boosting demand and output in France, Italy, Greece and elsewhere. It would also see somewhat more rapid inflation, which would make other countries’ goods and services relatively more competitive. Also, a more rapidly growing euro zone economy would likely increase the value of the euro, making U.S. goods and services more competitive compared with those produced in the euro zone.

Germany doesn’t boost demand in this way apparently because the country is tied up with nearly century old superstitions about inflation. Just as many people in the United States deny global warming in spite of massive evidence that it is real and humans are causing it, millions of Germans, including those in leadership positions, claim that modest increases in the inflation rate could lead to the sort of hyper-inflation the country experienced under Weimar, following World War I. There is absolutely no evidence to support this view, but it seems to guide German economic policy.

Using arithmetic in economic policy debates is always dangerous, but that would seem to be the implication of the NYT’s designation of Germany’s $64.8 billion trade surplus with the United States as “mammoth.” Since China’s $347.0 billion trade surplus was more than five times as large, it would seem that China’s surplus has to be five times massive. It usually is not talked about that way in the NYT and elsewhere.

Remarkably, the piece never focused on the real explanation for Germany’s large trade surplus. It insists on running budget surpluses, even though there continues to be widespread unemployment throughout the euro zone. This policy is far more harmful to the other euro zone countries than the United States.

If Germany ran budget deficits it would directly pull in more imports from its euro zone partners (and the United States), thereby boosting demand and output in France, Italy, Greece and elsewhere. It would also see somewhat more rapid inflation, which would make other countries’ goods and services relatively more competitive. Also, a more rapidly growing euro zone economy would likely increase the value of the euro, making U.S. goods and services more competitive compared with those produced in the euro zone.

Germany doesn’t boost demand in this way apparently because the country is tied up with nearly century old superstitions about inflation. Just as many people in the United States deny global warming in spite of massive evidence that it is real and humans are causing it, millions of Germans, including those in leadership positions, claim that modest increases in the inflation rate could lead to the sort of hyper-inflation the country experienced under Weimar, following World War I. There is absolutely no evidence to support this view, but it seems to guide German economic policy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I kind of love how ridiculous things get repeated endlessly by people who claim to be informed. In his NYT column, Avik Roy warned us against taking seriously the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) projections of a surge in the uninsured under the Republican health care plan.

“First, some caution regarding the C.B.O.’s numbers. The C.B.O. is chock-full of committed and talented public servants, but the agency is neither omniscient nor infallible. In 2010, when the Affordable Care Act was signed into law by President Barack Obama, the C.B.O. predicted that by 2017, 23 million Americans would be enrolled in the law’s new insurance exchanges. Only about 11 million actually are.

“That’s because the C.B.O. failed to account for how the A.C.A.’s insurance regulations would drive premiums up for relatively healthy individuals. A new study by researchers at the Department of Health and Human Services finds that for people buying coverage on their own, premiums have more than doubled in the Obamacare era. Most adversely affected have been those whose incomes — while modest — were not low enough to qualify for sufficient amounts of the A.C.A.’s insurance subsidies.

“While the C.B.O. was overly optimistic in 2010 about Obamacare, there’s a strong case that it is being overly pessimistic about the new House bill, the American Health Care Act.”

Actually, CBO was overly pessimistic about Obamacare. If we look to CBO’s last report on the Affordable Care Act, before the exchanges began operation in 2014, it projected that there would be 29 million people uninsured as of 2017 (Table 3). In its most recent analysis, it puts the number of uninsured in 2017 at 26 million (Table 4). In other words, the number of people who are uninsured under the ACA is 3 million fewer than CBO had predicted back in 2012.

In what world is overestimating the number of uninsured “overly optimistic?” It is true that fewer people are in the exchanges than CBO expected. This is due to the fact that more people have qualified for Medicaid and also more people are receiving employer-provided insurance, as fewer companies than expected dropped coverage.

But, so what? The point was to get people insured, not necessarily to have them insured through the exchanges.

So remember the facts when you read Roy’s NYT column giving his prognostications for the Republican health care reform. Here’s a guy who couldn’t even bother to get the basic numbers on the ACA right.

I kind of love how ridiculous things get repeated endlessly by people who claim to be informed. In his NYT column, Avik Roy warned us against taking seriously the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) projections of a surge in the uninsured under the Republican health care plan.

“First, some caution regarding the C.B.O.’s numbers. The C.B.O. is chock-full of committed and talented public servants, but the agency is neither omniscient nor infallible. In 2010, when the Affordable Care Act was signed into law by President Barack Obama, the C.B.O. predicted that by 2017, 23 million Americans would be enrolled in the law’s new insurance exchanges. Only about 11 million actually are.

“That’s because the C.B.O. failed to account for how the A.C.A.’s insurance regulations would drive premiums up for relatively healthy individuals. A new study by researchers at the Department of Health and Human Services finds that for people buying coverage on their own, premiums have more than doubled in the Obamacare era. Most adversely affected have been those whose incomes — while modest — were not low enough to qualify for sufficient amounts of the A.C.A.’s insurance subsidies.

“While the C.B.O. was overly optimistic in 2010 about Obamacare, there’s a strong case that it is being overly pessimistic about the new House bill, the American Health Care Act.”

Actually, CBO was overly pessimistic about Obamacare. If we look to CBO’s last report on the Affordable Care Act, before the exchanges began operation in 2014, it projected that there would be 29 million people uninsured as of 2017 (Table 3). In its most recent analysis, it puts the number of uninsured in 2017 at 26 million (Table 4). In other words, the number of people who are uninsured under the ACA is 3 million fewer than CBO had predicted back in 2012.

In what world is overestimating the number of uninsured “overly optimistic?” It is true that fewer people are in the exchanges than CBO expected. This is due to the fact that more people have qualified for Medicaid and also more people are receiving employer-provided insurance, as fewer companies than expected dropped coverage.

But, so what? The point was to get people insured, not necessarily to have them insured through the exchanges.

So remember the facts when you read Roy’s NYT column giving his prognostications for the Republican health care reform. Here’s a guy who couldn’t even bother to get the basic numbers on the ACA right.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT ran a piece discussing the efforts by various industry groups to ensure that they are not hurt by measures that reduce prescription drug prices. At one point, it listed some of these measures, noting a bill co-sponsored by Senator Bernie Sanders, which would allow drugs to be imported from Canada.

It is worth noting that this bill, which is co-sponsored by sixteen other senators including Elizabeth Warren, Sherrod Brown, and Kirsten Gillibrand, also includes mechanisms that would reduce the cost of drugs by not granting them patent monopolies that make their price high in the first place. One proposal would create a prize fund, which would allow for the patents on important new drugs to be purchased by the government and placed in the public domain. They could then be sold as generics as soon as they are put on the market.

The other provision would have the government finance some clinical trials of drugs after securing all patent rights. In this case, also the new drugs would be sold as generics. By paying for the trials (which would be conducted by private companies under contract), the government would be able to require that all test results were in the public domain.

This would allow doctors and other researchers to be able to determine if a particular drug was better for men than women, or appeared to cause bad reactions when mixed with other drugs. As it stands now, drug companies only have an incentive to publicly disclose information that they think will help them market their drugs. If the government paid for some number of clinical trials, it could help to set a new standard of disclosure with its practices, in addition to making new drugs available at generic prices.

The NYT ran a piece discussing the efforts by various industry groups to ensure that they are not hurt by measures that reduce prescription drug prices. At one point, it listed some of these measures, noting a bill co-sponsored by Senator Bernie Sanders, which would allow drugs to be imported from Canada.

It is worth noting that this bill, which is co-sponsored by sixteen other senators including Elizabeth Warren, Sherrod Brown, and Kirsten Gillibrand, also includes mechanisms that would reduce the cost of drugs by not granting them patent monopolies that make their price high in the first place. One proposal would create a prize fund, which would allow for the patents on important new drugs to be purchased by the government and placed in the public domain. They could then be sold as generics as soon as they are put on the market.

The other provision would have the government finance some clinical trials of drugs after securing all patent rights. In this case, also the new drugs would be sold as generics. By paying for the trials (which would be conducted by private companies under contract), the government would be able to require that all test results were in the public domain.

This would allow doctors and other researchers to be able to determine if a particular drug was better for men than women, or appeared to cause bad reactions when mixed with other drugs. As it stands now, drug companies only have an incentive to publicly disclose information that they think will help them market their drugs. If the government paid for some number of clinical trials, it could help to set a new standard of disclosure with its practices, in addition to making new drugs available at generic prices.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión