Aaron Carroll had an interesting Upshot piece comparing the merits of Medicaid and private insurance. It focuses on the fact that Medicaid is largely free for beneficiaries, while private insurance typically has substantial co-pays and deductibles. The piece points out that these fees can provide a substantial disincentive for getting health care, especially for lower income people.

While this might be a good way to save the system money if it discourages unnecessary care, which was a major reason the Affordable Care Act encouraged such fees, research shows that people also put off necessary care as a result of such fees. As a result, private insurance may end up leading to worse health outcomes than Medicaid for many low- and moderate-income people.

While this discussion is useful, there is another aspect to the fees that it ignores. Insurers often make mistakes which require patients to spend many extra hours pursuing claims. In many cases, they may not be compensated for care which should be covered if they don’t spend the necessary time. Even if they do get compensated, this is a needless waste of people’s time which is not factored into standard analysis on health care costs.

While it is always dangerous to generalize from very personal experiences, my guess is that my wife and I had to follow up in some manner on at least 20 percent of our claims. In some cases, this could be a single phone call, in other cases it could mean extensive back and forth between the provider and insurer, requiring multiple documents and authorizations. It is hard to believe that our experience is all that atypical or that we are especially bad at filling out forms. (My wife is also an economist who is pretty good at dealing with forms and numbers.)

Anyhow, this is an aspect of co-pays and deductibles that can be especially annoying to patients. Remember, people are most likely to be dealing with large numbers of claims when they are suffering from a health problem. This is not the best time to add another problem to their life.

Aaron Carroll had an interesting Upshot piece comparing the merits of Medicaid and private insurance. It focuses on the fact that Medicaid is largely free for beneficiaries, while private insurance typically has substantial co-pays and deductibles. The piece points out that these fees can provide a substantial disincentive for getting health care, especially for lower income people.

While this might be a good way to save the system money if it discourages unnecessary care, which was a major reason the Affordable Care Act encouraged such fees, research shows that people also put off necessary care as a result of such fees. As a result, private insurance may end up leading to worse health outcomes than Medicaid for many low- and moderate-income people.

While this discussion is useful, there is another aspect to the fees that it ignores. Insurers often make mistakes which require patients to spend many extra hours pursuing claims. In many cases, they may not be compensated for care which should be covered if they don’t spend the necessary time. Even if they do get compensated, this is a needless waste of people’s time which is not factored into standard analysis on health care costs.

While it is always dangerous to generalize from very personal experiences, my guess is that my wife and I had to follow up in some manner on at least 20 percent of our claims. In some cases, this could be a single phone call, in other cases it could mean extensive back and forth between the provider and insurer, requiring multiple documents and authorizations. It is hard to believe that our experience is all that atypical or that we are especially bad at filling out forms. (My wife is also an economist who is pretty good at dealing with forms and numbers.)

Anyhow, this is an aspect of co-pays and deductibles that can be especially annoying to patients. Remember, people are most likely to be dealing with large numbers of claims when they are suffering from a health problem. This is not the best time to add another problem to their life.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Senator Toomey is apparently too young to remember the financial crisis that resulted from the collapse of the housing bubble. He told the Washington Post that he thinks Medicare cost increases will lead to a financial crisis:

“‘It’s a guaranteed financial crisis if we don’t do something about our entitlement programs,’ said Sen. Patrick J. Toomey (R-Pa.), who has pushed for indexing Medicaid to a lower inflation rate. ‘It’s not a question of whether that happens, it’s just a question of when, and how devastating, that is.'”

While it is possible to see how higher Medicare costs would lead to larger budget deficits, if Toomey and his Republican colleagues decide never to raise taxes or cut other spending, there is no obvious way that this leads to a financial crisis. The last crisis came about because a housing bubble was fueled by loans. When housing prices collapsed, trillions of dollars in loans went bad. While this is a fairly straightforward story, it is very difficult to see how rising Medicare costs are more likely to lead to a financial crisis than a Superbowl victory by the Cleveland Browns.

It might have been helpful to point out to readers that the Senator doesn’t appear to know what he is talking about.

Senator Toomey is apparently too young to remember the financial crisis that resulted from the collapse of the housing bubble. He told the Washington Post that he thinks Medicare cost increases will lead to a financial crisis:

“‘It’s a guaranteed financial crisis if we don’t do something about our entitlement programs,’ said Sen. Patrick J. Toomey (R-Pa.), who has pushed for indexing Medicaid to a lower inflation rate. ‘It’s not a question of whether that happens, it’s just a question of when, and how devastating, that is.'”

While it is possible to see how higher Medicare costs would lead to larger budget deficits, if Toomey and his Republican colleagues decide never to raise taxes or cut other spending, there is no obvious way that this leads to a financial crisis. The last crisis came about because a housing bubble was fueled by loans. When housing prices collapsed, trillions of dollars in loans went bad. While this is a fairly straightforward story, it is very difficult to see how rising Medicare costs are more likely to lead to a financial crisis than a Superbowl victory by the Cleveland Browns.

It might have been helpful to point out to readers that the Senator doesn’t appear to know what he is talking about.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT is again spreading the absurd myth that Paul Ryan and other Republicans want a free market in health care. While it is very helpful to the Republicans to imply that they are trying to advance some grand principle, as opposed to just giving money to rich people, it is a lie on a par with climate denialism.

There are no government-granted patent monopolies in a free market. As a result of these government granted monopolies, we will pay more than $440 billion for prescription drugs this year. These drugs would likely cost less than $80 billion in a free market. The difference of more than $360 billion a year is a bit less than 2 percent of GDP more than seven times as much money as is at stake in the Republicans proposed Medicaid cuts. (Those cuts cover a decade, this is a single year figure.)

The same story applies to medical equipment. MRIs are cheap without patent protection.

It is possible to argue for the merits of government granted monopolies (I argue against them in chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free]), but it is not possible to deny that these monopolies are a government policy, not the free market. Paul Ryan has never indicated any opposition to government granted patent monopolies.

Similarly, we pay our doctors twice as much as their counterparts in other rich countries, costing us more than $80 billion a year in higher health care costs. This is due to the protectionist barriers enjoyed by our doctors, which protect them from both foreign and domestic competition. (This is covered in chapter 7 of Rigged.) Paul Ryan has never indicated a desire to remove the protectionist barriers that allow many doctors to reach the top one percent of income earners.

The government also privileges insurance contracts in many ways compared with other contracts. For example, with insurance contracts not disclosing relevant information can often void the contract. By contrast, with most contracts, the parties to the contract are responsible for learning relevant information themselves. Ryan has not indicated any desire to reverse this privileged position for insurance contracts.

It is very generous of the NYT to pretend that the Republicans are motivated by some sort of principle in their efforts to repeal the ACA, but the claim is absurd on its face. It does not deserve to be treated seriously, the repeal is about giving more money to rich people, end of story.

The NYT is again spreading the absurd myth that Paul Ryan and other Republicans want a free market in health care. While it is very helpful to the Republicans to imply that they are trying to advance some grand principle, as opposed to just giving money to rich people, it is a lie on a par with climate denialism.

There are no government-granted patent monopolies in a free market. As a result of these government granted monopolies, we will pay more than $440 billion for prescription drugs this year. These drugs would likely cost less than $80 billion in a free market. The difference of more than $360 billion a year is a bit less than 2 percent of GDP more than seven times as much money as is at stake in the Republicans proposed Medicaid cuts. (Those cuts cover a decade, this is a single year figure.)

The same story applies to medical equipment. MRIs are cheap without patent protection.

It is possible to argue for the merits of government granted monopolies (I argue against them in chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free]), but it is not possible to deny that these monopolies are a government policy, not the free market. Paul Ryan has never indicated any opposition to government granted patent monopolies.

Similarly, we pay our doctors twice as much as their counterparts in other rich countries, costing us more than $80 billion a year in higher health care costs. This is due to the protectionist barriers enjoyed by our doctors, which protect them from both foreign and domestic competition. (This is covered in chapter 7 of Rigged.) Paul Ryan has never indicated a desire to remove the protectionist barriers that allow many doctors to reach the top one percent of income earners.

The government also privileges insurance contracts in many ways compared with other contracts. For example, with insurance contracts not disclosing relevant information can often void the contract. By contrast, with most contracts, the parties to the contract are responsible for learning relevant information themselves. Ryan has not indicated any desire to reverse this privileged position for insurance contracts.

It is very generous of the NYT to pretend that the Republicans are motivated by some sort of principle in their efforts to repeal the ACA, but the claim is absurd on its face. It does not deserve to be treated seriously, the repeal is about giving more money to rich people, end of story.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Folks who passed their intro econ class know that it is net exports (exports minus imports) that affect output and employment. Not exports alone. Nonetheless, we find people like Washington Post columnist Robert Samuelson telling readers that Trump’s decision to pull out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) might undermine his agenda because “being outside these agreements [a TPP without the U.S. and European Union-Japan trade deal) would weaken U.S. exports.”

Since it is not exports that matter for output and employment, but net exports, it is not clear that Trump should be worried. The United States International Trade Commission (USITC) projected that the TPP would lead to a net loss of manufacturing jobs, meaning that it would increase imports more than exports. Since Trump made increasing manufacturing employment a centerpiece of his campaign, it doesn’t seem unreasonable that he would oppose a deal that is projected to reduce manufacturing employment.

It is also important to realize that the USITC projections rule out the possibility that some of the countries in the agreement may deliberately keep down the value of their currency to increase their trade surpluses, as they have done in the past. The TPP would reduce the ability of the United States to take measures to punish such behavior.

It is also worth noting that contrary to what Samuelson implies, the U.S. is generally helped, not hurt, when our trading partners remove barriers between them. If an EU-Japan trade deal actually leads to stronger growth for both sides, these countries will be better trading partners for the United States. (It is possible that the increased protectionism in the pact, associated with longer and stronger patent and copyright and related protections may do more to slow growth than the liberalization measures do to increase it.)

Folks who passed their intro econ class know that it is net exports (exports minus imports) that affect output and employment. Not exports alone. Nonetheless, we find people like Washington Post columnist Robert Samuelson telling readers that Trump’s decision to pull out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) might undermine his agenda because “being outside these agreements [a TPP without the U.S. and European Union-Japan trade deal) would weaken U.S. exports.”

Since it is not exports that matter for output and employment, but net exports, it is not clear that Trump should be worried. The United States International Trade Commission (USITC) projected that the TPP would lead to a net loss of manufacturing jobs, meaning that it would increase imports more than exports. Since Trump made increasing manufacturing employment a centerpiece of his campaign, it doesn’t seem unreasonable that he would oppose a deal that is projected to reduce manufacturing employment.

It is also important to realize that the USITC projections rule out the possibility that some of the countries in the agreement may deliberately keep down the value of their currency to increase their trade surpluses, as they have done in the past. The TPP would reduce the ability of the United States to take measures to punish such behavior.

It is also worth noting that contrary to what Samuelson implies, the U.S. is generally helped, not hurt, when our trading partners remove barriers between them. If an EU-Japan trade deal actually leads to stronger growth for both sides, these countries will be better trading partners for the United States. (It is possible that the increased protectionism in the pact, associated with longer and stronger patent and copyright and related protections may do more to slow growth than the liberalization measures do to increase it.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In order to reduce speculation in its housing market, the city of Vancouver imposed a vacant property tax. People would be assessed an additional tax if a house or apartment was left vacant for a long period of time. (Yes, this is one of my pet ideas, so it makes my day to see Vancouver moving ahead with the vacancy tax.)

In addition to reducing speculation it might be expected that the tax would reduce rents by making more units available. But CBC says it ain’t so, there will be more supply but no change in prices. Interesting how things work up north.

In order to reduce speculation in its housing market, the city of Vancouver imposed a vacant property tax. People would be assessed an additional tax if a house or apartment was left vacant for a long period of time. (Yes, this is one of my pet ideas, so it makes my day to see Vancouver moving ahead with the vacancy tax.)

In addition to reducing speculation it might be expected that the tax would reduce rents by making more units available. But CBC says it ain’t so, there will be more supply but no change in prices. Interesting how things work up north.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes, that is what he said. You can read about it in the NYT. The annualized rate of wage growth in the last three months compared with the prior three months was just 2.0 percent. So, if there is a problem with getting qualified workers it seems to be primarily in the human resources department.

Yes, that is what he said. You can read about it in the NYT. The annualized rate of wage growth in the last three months compared with the prior three months was just 2.0 percent. So, if there is a problem with getting qualified workers it seems to be primarily in the human resources department.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

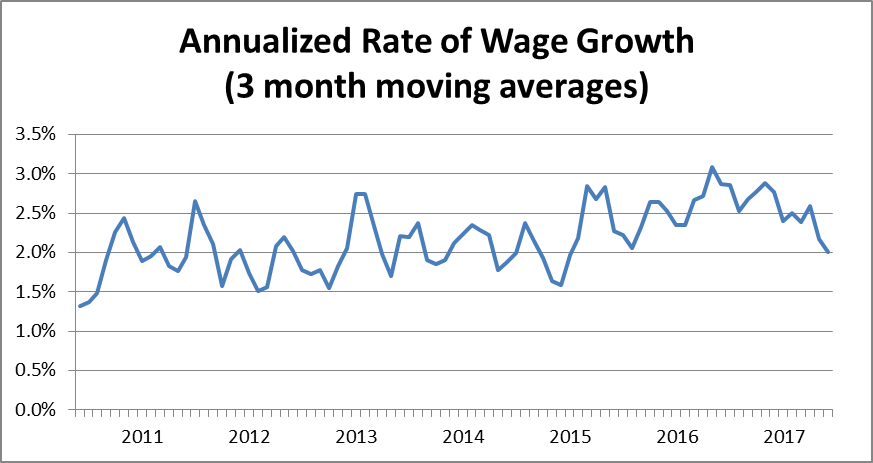

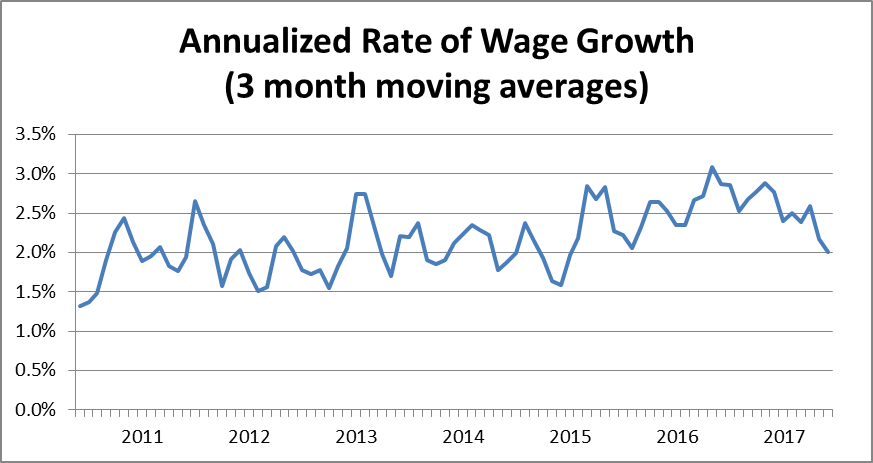

If the Fed is really targeting 2.0 percent inflation, it is hard to understand why it would be considering further interest rate hikes. Inflation has been slowing in recent months, to a rate of just 1.4 percent in the core personal consumption expenditure deflator. The June jobs report gave more evidence that wage growth is slowing as well. The figure below shows the annualized rate of inflation taking the average hourly wage for the last three months (April, May, and June), compared with the average for the prior three months (January, February, and March).

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen, there was some acceleration in wage growth by this measure in the first half of 2016, with a peak of just over 3.0 percent in May. Since then the general direction has been downward. The most recent data puts the annualized rate of wage growth by this measure at just over 2.0 percent. We all know the story that wage growth is supposed to accelerate in a tight labor market, but maybe the data are trying to tell us that the labor market just isn’t very tight.

If the Fed is really targeting 2.0 percent inflation, it is hard to understand why it would be considering further interest rate hikes. Inflation has been slowing in recent months, to a rate of just 1.4 percent in the core personal consumption expenditure deflator. The June jobs report gave more evidence that wage growth is slowing as well. The figure below shows the annualized rate of inflation taking the average hourly wage for the last three months (April, May, and June), compared with the average for the prior three months (January, February, and March).

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen, there was some acceleration in wage growth by this measure in the first half of 2016, with a peak of just over 3.0 percent in May. Since then the general direction has been downward. The most recent data puts the annualized rate of wage growth by this measure at just over 2.0 percent. We all know the story that wage growth is supposed to accelerate in a tight labor market, but maybe the data are trying to tell us that the labor market just isn’t very tight.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

An NYT piece on the growth of oil exports may have given readers a misleading impression of the state of the U.S. oil industry. The piece was headlined, “oil exports, illegal for decades, now fuel a Texas port boom.” It told readers:

“Oil exports grew slowly through most of 2016, but this year there has been a surge reaching 1.3 million barrels a day — roughly 15 percent of domestic production — which even at today’s depressed prices is worth more than $1.5 billion a month.”

It is worth noting that the rise in oil exports has been accompanied by a rise in oil imports. According to the Energy Information Agency, imports of crude and petroleum products bottomed out at 9.2 million barrels a day in 2014. By 2016, imports had risen by more than 900,000 barrels a day to 10.1 million.

By allowing exports of oil, some oil that would have otherwise been consumed domestically is instead being exported. This oil is being replaced by oil from other countries. While this opening of trade increases efficiency, if we ignore the environmental costs associated with more transportation of oil and petroleum products, it means somewhat higher prices for domestic consumers.

The oil that is being imported almost certainly costs more than the domestically produced oil that is now being exported instead of sold domestically. It would have been helpful to note this fact in the article.

An NYT piece on the growth of oil exports may have given readers a misleading impression of the state of the U.S. oil industry. The piece was headlined, “oil exports, illegal for decades, now fuel a Texas port boom.” It told readers:

“Oil exports grew slowly through most of 2016, but this year there has been a surge reaching 1.3 million barrels a day — roughly 15 percent of domestic production — which even at today’s depressed prices is worth more than $1.5 billion a month.”

It is worth noting that the rise in oil exports has been accompanied by a rise in oil imports. According to the Energy Information Agency, imports of crude and petroleum products bottomed out at 9.2 million barrels a day in 2014. By 2016, imports had risen by more than 900,000 barrels a day to 10.1 million.

By allowing exports of oil, some oil that would have otherwise been consumed domestically is instead being exported. This oil is being replaced by oil from other countries. While this opening of trade increases efficiency, if we ignore the environmental costs associated with more transportation of oil and petroleum products, it means somewhat higher prices for domestic consumers.

The oil that is being imported almost certainly costs more than the domestically produced oil that is now being exported instead of sold domestically. It would have been helpful to note this fact in the article.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The magic word shows up yet again in an NYT piece on a trade agreement being negotiated between Japan and the European Union. While the deal clearly includes some moves towards trade liberalization, which are discussed in the piece, it likely also includes measures for stronger and longer protections for patents, copyrights, and other forms of intellectual property. These protectionist measures may well outweigh the liberalizing effect of reductions in tariffs and other conventional barriers to trade.

If that is the case, it is clearly wrong to call the deal a “free” trade agreement, since it on net would be increasing protectionism. I don’t happen to know the balance in this pact, but I suspect the NYT doesn’t either. In that case, it would be at least as informative to readers to simply call the deal a “trade agreement” and save a word.

The magic word shows up yet again in an NYT piece on a trade agreement being negotiated between Japan and the European Union. While the deal clearly includes some moves towards trade liberalization, which are discussed in the piece, it likely also includes measures for stronger and longer protections for patents, copyrights, and other forms of intellectual property. These protectionist measures may well outweigh the liberalizing effect of reductions in tariffs and other conventional barriers to trade.

If that is the case, it is clearly wrong to call the deal a “free” trade agreement, since it on net would be increasing protectionism. I don’t happen to know the balance in this pact, but I suspect the NYT doesn’t either. In that case, it would be at least as informative to readers to simply call the deal a “trade agreement” and save a word.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión