Donald Trump can boast at least a little bit about the return of manufacturing jobs during his presidency. Employment in the sector is up by 125,000 since January. It’s not exactly a boom, after all, we are still down by almost 1.3 million jobs from the pre-recession level and 4.8 million from where we were in 2000, but at least it is movement in a positive direction.

In an NYT Upshot piece, Neil Irwin sorts out the reasons for this modest uptick in manufacturing jobs. He points to a small increase in oil prices and a drop in the dollar, both of which are likely factors. (He also points to weak growth in government employment. I’m not sure how that matters here.)

However, Irwin left out what might be the most important reason for the increase in manufacturing jobs: weak productivity growth. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, output in manufacturing has increased at 2.0 percent annual rate in the first half of 2017. This would mean that if we had a modest 2.0 percent rate of increase in productivity in the sector (manufacturing productivity usually grows faster than the rest of the economy), we would have no need for more labor, and presumably no new jobs.

But now America is great again, manufacturing productivity has slowed to a crawl, increasing at just a 1.4 percent annual rate in the first half of the year. So, there we have it, extraordinarily weak productivity has translated into 125,000 new manufacturing jobs under President Trump.

Donald Trump can boast at least a little bit about the return of manufacturing jobs during his presidency. Employment in the sector is up by 125,000 since January. It’s not exactly a boom, after all, we are still down by almost 1.3 million jobs from the pre-recession level and 4.8 million from where we were in 2000, but at least it is movement in a positive direction.

In an NYT Upshot piece, Neil Irwin sorts out the reasons for this modest uptick in manufacturing jobs. He points to a small increase in oil prices and a drop in the dollar, both of which are likely factors. (He also points to weak growth in government employment. I’m not sure how that matters here.)

However, Irwin left out what might be the most important reason for the increase in manufacturing jobs: weak productivity growth. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, output in manufacturing has increased at 2.0 percent annual rate in the first half of 2017. This would mean that if we had a modest 2.0 percent rate of increase in productivity in the sector (manufacturing productivity usually grows faster than the rest of the economy), we would have no need for more labor, and presumably no new jobs.

But now America is great again, manufacturing productivity has slowed to a crawl, increasing at just a 1.4 percent annual rate in the first half of the year. So, there we have it, extraordinarily weak productivity has translated into 125,000 new manufacturing jobs under President Trump.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Fans of economic policy are used to the old “night is day,” “down is up,” approach to economic policy. After all, much of the media are worried about robots taking all the jobs even as the data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that productivity growth (the rate at which robots are taking jobs) is at a record slow pace.

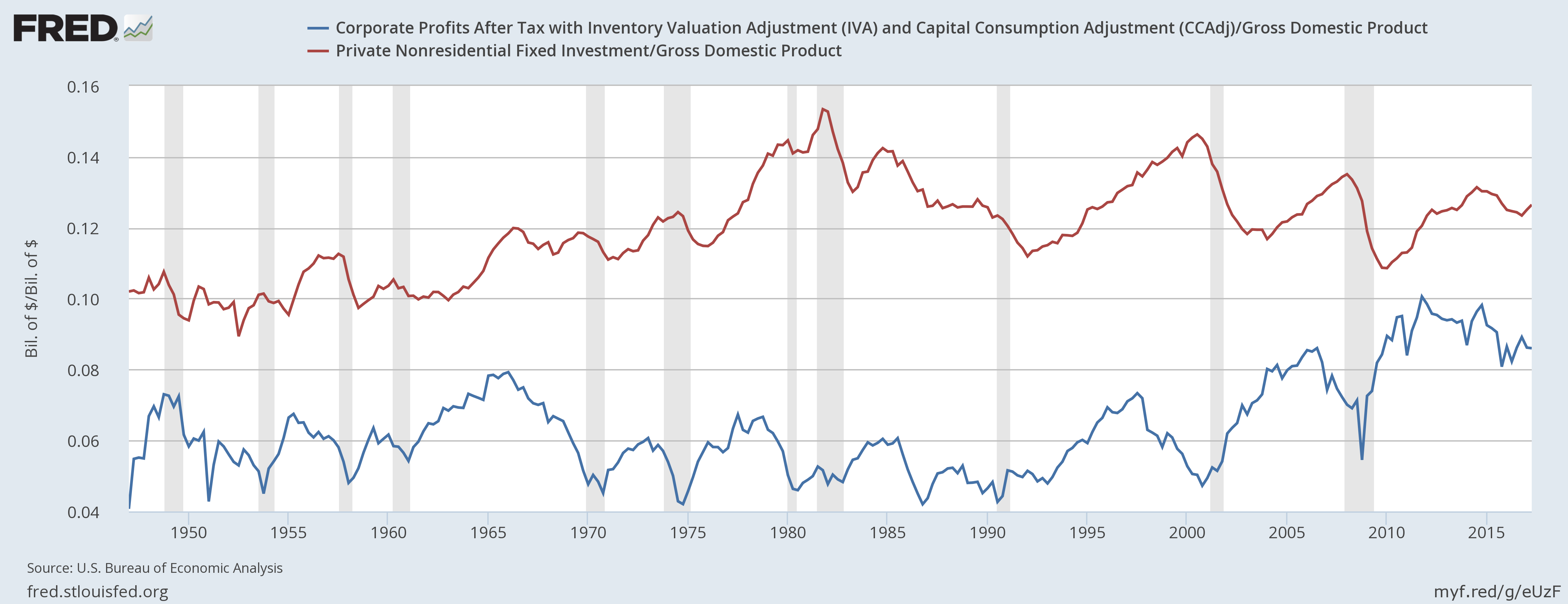

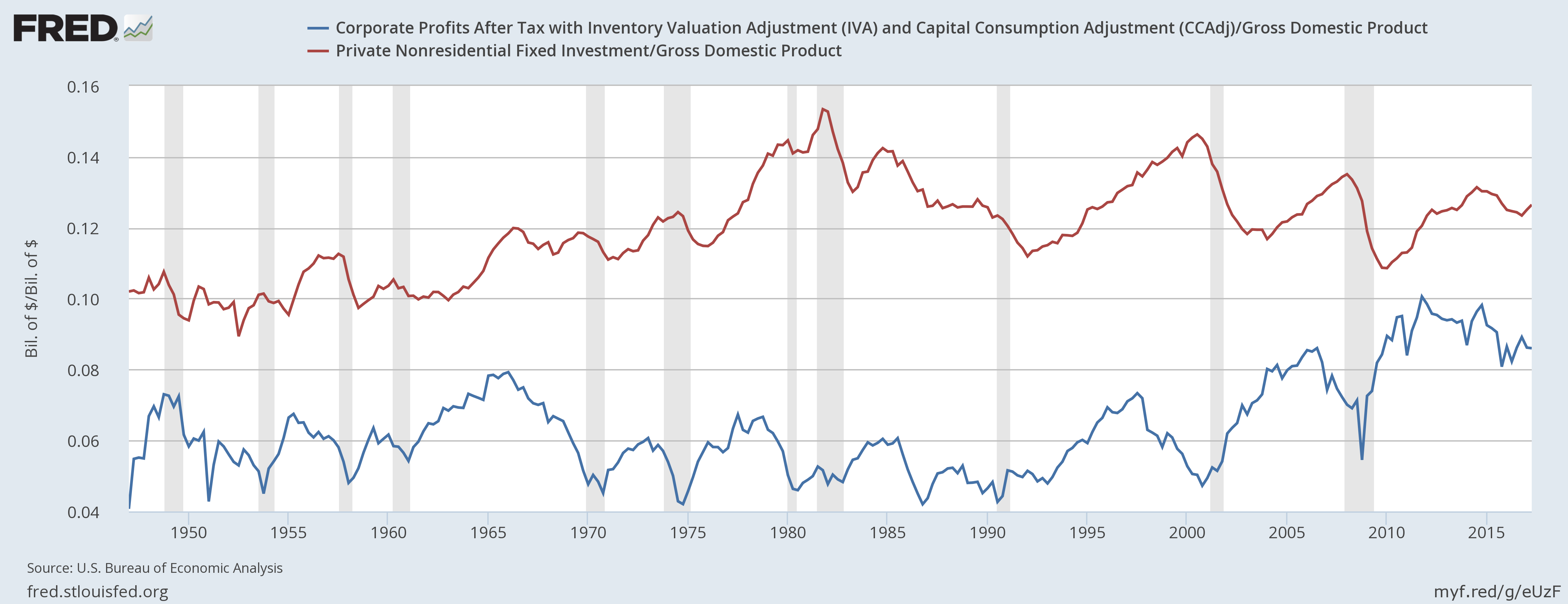

That’s why it is hardly surprising to hear the argument being taken seriously that reducing corporate taxes will lead to more investment and thereby greater wage growth in the future. The data from the last seventy years show there is no relationship between aggregate profits and investment.

As can be seen, there is no evidence that higher corporate profits are associated with an increase in investment. In fact, the peak investment share of GDP was reached in the early 1980s when the after-tax profit share was near its post war low. Investment hit a second peak in 2000, even as the profit share was falling through the second half of the decade. The profit share rose sharply in the 2000s, even as the investment share stagnated. In short, you need a pretty good imagination to look at this data and think that increasing after-tax profits will somehow cause firms to invest more.

Having said this, there is a good argument for reforming the tax code in a way the reduces the opportunities for gaming. The tax avoidance industry is both an enormous waste and an important source of inequality. The resources spent on avoiding taxes, in the form of lawyers, accountants, and corporate engineering, are a complete waste from an economic standpoint. Also running tax avoidance scams allows some people to get very rich. The private equity industry is to a large extent a tax avoidance scam.

So it would be a big gain for the country if the tax code could be restructured in a way that eliminates most of the opportunities for gaming. As I have written before, my preferred approach is requiring companies to turn over a percentage of their stock in the form of non-voting shares, which would be treated exactly like voting shares in terms of dividends and buybacks. This would make it impossible for companies to cheat the government unless it was also cheating its stockholders.

Anyhow, that my preferred route, but it’s probably too simple to get anywhere.

Fans of economic policy are used to the old “night is day,” “down is up,” approach to economic policy. After all, much of the media are worried about robots taking all the jobs even as the data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that productivity growth (the rate at which robots are taking jobs) is at a record slow pace.

That’s why it is hardly surprising to hear the argument being taken seriously that reducing corporate taxes will lead to more investment and thereby greater wage growth in the future. The data from the last seventy years show there is no relationship between aggregate profits and investment.

As can be seen, there is no evidence that higher corporate profits are associated with an increase in investment. In fact, the peak investment share of GDP was reached in the early 1980s when the after-tax profit share was near its post war low. Investment hit a second peak in 2000, even as the profit share was falling through the second half of the decade. The profit share rose sharply in the 2000s, even as the investment share stagnated. In short, you need a pretty good imagination to look at this data and think that increasing after-tax profits will somehow cause firms to invest more.

Having said this, there is a good argument for reforming the tax code in a way the reduces the opportunities for gaming. The tax avoidance industry is both an enormous waste and an important source of inequality. The resources spent on avoiding taxes, in the form of lawyers, accountants, and corporate engineering, are a complete waste from an economic standpoint. Also running tax avoidance scams allows some people to get very rich. The private equity industry is to a large extent a tax avoidance scam.

So it would be a big gain for the country if the tax code could be restructured in a way that eliminates most of the opportunities for gaming. As I have written before, my preferred approach is requiring companies to turn over a percentage of their stock in the form of non-voting shares, which would be treated exactly like voting shares in terms of dividends and buybacks. This would make it impossible for companies to cheat the government unless it was also cheating its stockholders.

Anyhow, that my preferred route, but it’s probably too simple to get anywhere.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

One of the ways in which the government pays for things it wants done is to grant patent and copyright monopolies. This is not a statement about the merits of patents and copyrights as mechanisms for financing research and creative work; it is a definition. The government grants these monopolies to allow companies to charge prices that are far above the free market price as a reward for its past innovation or creative work.

In this way, patent or copyright monopoly can be thought as being like a privately imposed tax. If a drug company like Gilead Sciences can charge $84,000 for a Sovaldi, when the free market price would be something like $300, it has the same effect on the public as if the government imposed a tax of 28,000 percent on Sovaldi. It is the same amount of money out of people’s pockets.

We can argue about the merits of patent and copyright monopolies (see chapter 5 in Rigged [it’s free]), but the fact that they are alternative mechanisms that the government uses to finance research and creative work is not an arguable point. If we spent another $400 billion a year on research (roughly 20 percent of annual income tax collections), this would show up in the deficit and add to the debt. Yet somehow we are supposed to not pay attention when the government grants patents and copyrights that add hundreds of billions of dollars to what we pay for drugs, medical equipment, software and other protected items. (By my calculation, drug patents and related protections add close to $400 billion to what we spend each year on prescription drugs alone.)

This obvious point is missing from almost all the whining about the debt and deficit (see here for today’s example). The additional costs the public pays for items as a result of granting patent and copyright monopolies are never mentioned as burdens imposed on future generations. Somehow, we are not supposed to be concerned about making our kids pay huge amounts of money to Pfizer and Microsoft, it’s only a burden when the money has to be paid to the government.

That might fly as cheap political rhetoric, but it doesn’t make sense. And the people who talk about debts and deficits without mentioning patent monopolies deserve only ridicule, they should not be taken seriously.

One of the ways in which the government pays for things it wants done is to grant patent and copyright monopolies. This is not a statement about the merits of patents and copyrights as mechanisms for financing research and creative work; it is a definition. The government grants these monopolies to allow companies to charge prices that are far above the free market price as a reward for its past innovation or creative work.

In this way, patent or copyright monopoly can be thought as being like a privately imposed tax. If a drug company like Gilead Sciences can charge $84,000 for a Sovaldi, when the free market price would be something like $300, it has the same effect on the public as if the government imposed a tax of 28,000 percent on Sovaldi. It is the same amount of money out of people’s pockets.

We can argue about the merits of patent and copyright monopolies (see chapter 5 in Rigged [it’s free]), but the fact that they are alternative mechanisms that the government uses to finance research and creative work is not an arguable point. If we spent another $400 billion a year on research (roughly 20 percent of annual income tax collections), this would show up in the deficit and add to the debt. Yet somehow we are supposed to not pay attention when the government grants patents and copyrights that add hundreds of billions of dollars to what we pay for drugs, medical equipment, software and other protected items. (By my calculation, drug patents and related protections add close to $400 billion to what we spend each year on prescription drugs alone.)

This obvious point is missing from almost all the whining about the debt and deficit (see here for today’s example). The additional costs the public pays for items as a result of granting patent and copyright monopolies are never mentioned as burdens imposed on future generations. Somehow, we are not supposed to be concerned about making our kids pay huge amounts of money to Pfizer and Microsoft, it’s only a burden when the money has to be paid to the government.

That might fly as cheap political rhetoric, but it doesn’t make sense. And the people who talk about debts and deficits without mentioning patent monopolies deserve only ridicule, they should not be taken seriously.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a piece on efforts to reduce loopholes to ensure the government actually collects in taxes something close to the targeted rate. The piece likely left readers with the belief that it was not possible to establish such a system.

Actually, it is not hard. If the government required companies to turn over a percentage of its stock in the form of non-voting shares, which are treated exactly like voting shares in terms of dividends and buybacks, it would be impossible for companies to cheat the government unless it was also cheating its stockholders. This means that if the targeted tax rate is 25 percent, companies turn over an amount of shares equal to 25 percent of the total. If the company pays a $2 dividend to its other shares, it also pays a $2 dividend to the government. If it buys back 10 percent of its shares at $100 each, it also buys back 10 percent of the government’s shares at $100 each.

Anyhow, we could construct this sort of share system to ensure the government gets its share of corporate profits, but it’s probably too simple for policy types to understand.

Addendum

An important point that is often missed in this debate is that the tax avoidance industry is both an enormous waste and an important source of inequality. The resources spent on avoiding taxes, in the form of lawyers, accountants, and corporate engineering, are a complete waste from an economic standpoint. Also, running tax avoidance scams allows some people to get very rich. The private equity industry is to a large extent a tax avoidance scam. It has produced some of the very richest people in the country. For this reason, a reform to the tax code that substantially reduced the opportunities for gaming would be a big gain from a progressive perspective even if led to a small loss of tax revenue from the corporate sector.

The NYT had a piece on efforts to reduce loopholes to ensure the government actually collects in taxes something close to the targeted rate. The piece likely left readers with the belief that it was not possible to establish such a system.

Actually, it is not hard. If the government required companies to turn over a percentage of its stock in the form of non-voting shares, which are treated exactly like voting shares in terms of dividends and buybacks, it would be impossible for companies to cheat the government unless it was also cheating its stockholders. This means that if the targeted tax rate is 25 percent, companies turn over an amount of shares equal to 25 percent of the total. If the company pays a $2 dividend to its other shares, it also pays a $2 dividend to the government. If it buys back 10 percent of its shares at $100 each, it also buys back 10 percent of the government’s shares at $100 each.

Anyhow, we could construct this sort of share system to ensure the government gets its share of corporate profits, but it’s probably too simple for policy types to understand.

Addendum

An important point that is often missed in this debate is that the tax avoidance industry is both an enormous waste and an important source of inequality. The resources spent on avoiding taxes, in the form of lawyers, accountants, and corporate engineering, are a complete waste from an economic standpoint. Also, running tax avoidance scams allows some people to get very rich. The private equity industry is to a large extent a tax avoidance scam. It has produced some of the very richest people in the country. For this reason, a reform to the tax code that substantially reduced the opportunities for gaming would be a big gain from a progressive perspective even if led to a small loss of tax revenue from the corporate sector.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I may have missed it, but the coverage of Dara Khosrowshahi’s pick to be the CEO of Uber seemed to leave out the fact that he is a board member of the New York Times. This would seem to be a point worth mentioning in his profiles. It’s also an item that we would especially expect to see in NYT pieces on Mr. Khosrowshahi.

I may have missed it, but the coverage of Dara Khosrowshahi’s pick to be the CEO of Uber seemed to leave out the fact that he is a board member of the New York Times. This would seem to be a point worth mentioning in his profiles. It’s also an item that we would especially expect to see in NYT pieces on Mr. Khosrowshahi.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The 11 countries left in the Trans-Pacific Partnership following the withdrawal of the United States are still looking to finalize the deal. One of the changes they are considering, now that the U.S. has left, is to eliminate rules that would require countries to strengthen patent-related protections for prescription drugs. These protections could hugely raise the price of prescription drugs. Patents and related protections can often be equivalent to tariffs of several thousand percent on the protected items.

The push to remove the protectionist rules is apparently coming from Vietnam. Now that the U.S. pharmaceutical industry is no longer at the table, the remaining countries seem willing to go along. If the final deal excludes these rules, it could be a useful precedent for other trade deals.

The 11 countries left in the Trans-Pacific Partnership following the withdrawal of the United States are still looking to finalize the deal. One of the changes they are considering, now that the U.S. has left, is to eliminate rules that would require countries to strengthen patent-related protections for prescription drugs. These protections could hugely raise the price of prescription drugs. Patents and related protections can often be equivalent to tariffs of several thousand percent on the protected items.

The push to remove the protectionist rules is apparently coming from Vietnam. Now that the U.S. pharmaceutical industry is no longer at the table, the remaining countries seem willing to go along. If the final deal excludes these rules, it could be a useful precedent for other trade deals.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Reporters in principle have the ability to get behind the assertions of politicians to tell readers whether they are true or not. Unlike most news readers, they are supposed to have the time and necessary expertise to assess claims being made.

This is why it is striking that Politico reported on the strategy of Trump and Republicans to present their tax cut plan as a populist measure for the middle class as though they were reviewing a play at the theater. While the specifics of the Trump/Republican plan are not yet known, the outline is. It will feature large tax cuts for the rich and trivial tax cuts for everyone else. If the cost of the tax cuts is offset by spending cuts, the typical middle-class family is virtually certain to end up a big loser.

In other words, presenting the tax cut as a populist measure aimed at helping the middle class at the expense of the rich is a lie. Politico’s reporters presumably know it is a lie, but decided not to share this information with readers. Apparently, they want to assist Trump and the Republicans in their efforts to deceive the public so that the rich can be made even richer with this tax cut.

Reporters in principle have the ability to get behind the assertions of politicians to tell readers whether they are true or not. Unlike most news readers, they are supposed to have the time and necessary expertise to assess claims being made.

This is why it is striking that Politico reported on the strategy of Trump and Republicans to present their tax cut plan as a populist measure for the middle class as though they were reviewing a play at the theater. While the specifics of the Trump/Republican plan are not yet known, the outline is. It will feature large tax cuts for the rich and trivial tax cuts for everyone else. If the cost of the tax cuts is offset by spending cuts, the typical middle-class family is virtually certain to end up a big loser.

In other words, presenting the tax cut as a populist measure aimed at helping the middle class at the expense of the rich is a lie. Politico’s reporters presumably know it is a lie, but decided not to share this information with readers. Apparently, they want to assist Trump and the Republicans in their efforts to deceive the public so that the rich can be made even richer with this tax cut.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

We are seeing many terrible pictures from Houston as a result of Hurricane Harvey. People with young children and pets are wading through high water in the hope of being rescued by boat or helicopter. Elderly people in nursing homes are sitting in waist high water waiting to be rescued. It’s a pretty horrible story.

One thing we can feel good about is that because the United States is a wealthy country, we do have large numbers of boats and helicopters and trained rescue workers able to assist the victims of the storm. We also have places where we can take these people where they will have shelter, as well access to food and medical care. However bad the human toll will be from Harvey, it would be hugely worse without these resources.

This might be a good time for people to take a moment to think about Bangladesh, a densely populated country on the other side of the world. More than 160 million people live in Bangladesh. Almost half of these people live in low-lying areas with an elevation of less than 10 meters (33 feet) above sea level.

Bangladesh experiences seasonal monsoon rains which invariably lead to flooding, as well as occasional cyclones. The monsoon rains and cyclones are likely to get worse in the years ahead, as one of the effects of global warming. This will mean that the flooding will be worse.

Bangladesh does not have large amounts of resources to assist the people whose homes are flooded. It does not have the same number of boats and helicopters and trained rescue workers to save people trapped by rising water. Nor can it guarantee that people who do escape will have access to adequate shelter, medical care, or even clean drinking water. This means many more people are likely to be dying from floods in Bangladesh in part as a result of the impact of global warming.

Emissions of the greenhouse gases responsible for global warming are often treated as a natural market outcome, whereas efforts to restrict emissions are viewed as government intervention. This is nonsense.

Allowing people to emit greenhouse gases without paying for the damage done is like allowing them to dump their sewage on their neighbor’s lawn. Everyone understands that we are responsible for dealing with our own sewage and not imposing a cost on our neighbor. It’s the same story with greenhouse gases.

It is understandable that a rich jerk like Donald Trump might not want to pay for the damage he does to the world, especially when the people most affected are dark-skinned, but it is not a serious position. The emissions from the United States and other wealthy countries will result in a lot of Harvey-like disasters in Bangladesh and elsewhere in the developing world. We have to take responsibility for this human catastrophe.

We are seeing many terrible pictures from Houston as a result of Hurricane Harvey. People with young children and pets are wading through high water in the hope of being rescued by boat or helicopter. Elderly people in nursing homes are sitting in waist high water waiting to be rescued. It’s a pretty horrible story.

One thing we can feel good about is that because the United States is a wealthy country, we do have large numbers of boats and helicopters and trained rescue workers able to assist the victims of the storm. We also have places where we can take these people where they will have shelter, as well access to food and medical care. However bad the human toll will be from Harvey, it would be hugely worse without these resources.

This might be a good time for people to take a moment to think about Bangladesh, a densely populated country on the other side of the world. More than 160 million people live in Bangladesh. Almost half of these people live in low-lying areas with an elevation of less than 10 meters (33 feet) above sea level.

Bangladesh experiences seasonal monsoon rains which invariably lead to flooding, as well as occasional cyclones. The monsoon rains and cyclones are likely to get worse in the years ahead, as one of the effects of global warming. This will mean that the flooding will be worse.

Bangladesh does not have large amounts of resources to assist the people whose homes are flooded. It does not have the same number of boats and helicopters and trained rescue workers to save people trapped by rising water. Nor can it guarantee that people who do escape will have access to adequate shelter, medical care, or even clean drinking water. This means many more people are likely to be dying from floods in Bangladesh in part as a result of the impact of global warming.

Emissions of the greenhouse gases responsible for global warming are often treated as a natural market outcome, whereas efforts to restrict emissions are viewed as government intervention. This is nonsense.

Allowing people to emit greenhouse gases without paying for the damage done is like allowing them to dump their sewage on their neighbor’s lawn. Everyone understands that we are responsible for dealing with our own sewage and not imposing a cost on our neighbor. It’s the same story with greenhouse gases.

It is understandable that a rich jerk like Donald Trump might not want to pay for the damage he does to the world, especially when the people most affected are dark-skinned, but it is not a serious position. The emissions from the United States and other wealthy countries will result in a lot of Harvey-like disasters in Bangladesh and elsewhere in the developing world. We have to take responsibility for this human catastrophe.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Someone who had no knowledge of trade deals like NAFTA and the TPP would be justified in thinking they must be really bad news since their supporters have to make up obviously absurd claims to push their position. George Will is on the job this morning in his Washington Post column.

“Mark Perry of the American Enterprise Institute says that in the past 20 years the inflation-adjusted value of U.S. manufacturing output has increased 40 percent even though — actually, partly because — U.S. factory employment decreased 5.1 million jobs (29 percent). Manufacturing’s share of gross domestic product is almost unchanged since 1960. ‘US manufacturing output was near a record high last year at $1.91 trillion, just slightly below the 2007 level of $1.92 trillion, and will likely reach a new record high later this year,’ Perry writes. That record will be reached with about the same level of factory workers (fewer than 12.5 million) as in the early 1940s, when the U.S. population was about 135 million. Increased productivity is the reason there can be quadrupled output from the same number of workers. According to one study, 88 percent of manufacturing job losses are the result of improved productivity, not ‘rapacious’ Chinese.”

Okay, this one is in “how stupid do you think we are?” department. Guess what, the tree in my backyard is taller than ever before. Imagine that?

Yes, economies grow through time and so does productivity. That means that, in general, we expect output in most areas, like cell phones, haircuts, and manufactured goods to increase through time. So telling us we are near record levels of manufacturing output is basically telling us absolutely nothing. It is the sort of thing that only a cheap demagogue or someone totally ignorant of economics would do.

The basic story is that we have seen productivity growth in manufacturing as in all areas. Since growth has been somewhat faster in manufacturing, it has meant that manufacturing jobs have declined as a share of total employment, but generally, the increase in demand has been enough to keep employment in the sector roughly constant. The big exception was the period when our trade deficit exploded at the start of the last decade, eventually reaching almost 6.0 percent of GDP.

Here’s the picture.

Manufacturing Jobs

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen, there is relatively little change, apart from cyclical ups or downs, in manufacturing jobs from 1970 until the late 1990s. Employment then plunges in the first half of the 2000s (before the Great Recession) due to the explosion of the trade deficit. This job loss was due to trade, but George Will and other supporters of U.S. trade policy think they have to lie to people and deny this fact.

While the trade deficit has declined somewhat in more recent years due to the drop in the value of the dollar, it is still near 3 percent of GDP (around $540 billion a year). The idea that it would not create more manufacturing jobs if we had more nearly balanced trade is absurd on its face (i.e. we could produce another $500 billion in manufactured goods every year without employing more workers), but apparently folks like George Will and the Washington Post editors want us to believe it.

Since we’re on the topic of lying to promote trade deals designed to redistribute upward let’s again note the famous 2007 Washington Post editorial touting NAFTA that told readers:

“Mexico’s gross domestic product, now more than $875 billion, has more than quadrupled since 1987.”

According to the IMF, Mexico’s GDP grew by 83 percent over this period, which is pretty far from quadrupling. Honest newspapers correct their mistakes, but as the slogan at the Washington Post says, “lies in the service of giving more money to rich people are no vice.”

Someone who had no knowledge of trade deals like NAFTA and the TPP would be justified in thinking they must be really bad news since their supporters have to make up obviously absurd claims to push their position. George Will is on the job this morning in his Washington Post column.

“Mark Perry of the American Enterprise Institute says that in the past 20 years the inflation-adjusted value of U.S. manufacturing output has increased 40 percent even though — actually, partly because — U.S. factory employment decreased 5.1 million jobs (29 percent). Manufacturing’s share of gross domestic product is almost unchanged since 1960. ‘US manufacturing output was near a record high last year at $1.91 trillion, just slightly below the 2007 level of $1.92 trillion, and will likely reach a new record high later this year,’ Perry writes. That record will be reached with about the same level of factory workers (fewer than 12.5 million) as in the early 1940s, when the U.S. population was about 135 million. Increased productivity is the reason there can be quadrupled output from the same number of workers. According to one study, 88 percent of manufacturing job losses are the result of improved productivity, not ‘rapacious’ Chinese.”

Okay, this one is in “how stupid do you think we are?” department. Guess what, the tree in my backyard is taller than ever before. Imagine that?

Yes, economies grow through time and so does productivity. That means that, in general, we expect output in most areas, like cell phones, haircuts, and manufactured goods to increase through time. So telling us we are near record levels of manufacturing output is basically telling us absolutely nothing. It is the sort of thing that only a cheap demagogue or someone totally ignorant of economics would do.

The basic story is that we have seen productivity growth in manufacturing as in all areas. Since growth has been somewhat faster in manufacturing, it has meant that manufacturing jobs have declined as a share of total employment, but generally, the increase in demand has been enough to keep employment in the sector roughly constant. The big exception was the period when our trade deficit exploded at the start of the last decade, eventually reaching almost 6.0 percent of GDP.

Here’s the picture.

Manufacturing Jobs

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen, there is relatively little change, apart from cyclical ups or downs, in manufacturing jobs from 1970 until the late 1990s. Employment then plunges in the first half of the 2000s (before the Great Recession) due to the explosion of the trade deficit. This job loss was due to trade, but George Will and other supporters of U.S. trade policy think they have to lie to people and deny this fact.

While the trade deficit has declined somewhat in more recent years due to the drop in the value of the dollar, it is still near 3 percent of GDP (around $540 billion a year). The idea that it would not create more manufacturing jobs if we had more nearly balanced trade is absurd on its face (i.e. we could produce another $500 billion in manufactured goods every year without employing more workers), but apparently folks like George Will and the Washington Post editors want us to believe it.

Since we’re on the topic of lying to promote trade deals designed to redistribute upward let’s again note the famous 2007 Washington Post editorial touting NAFTA that told readers:

“Mexico’s gross domestic product, now more than $875 billion, has more than quadrupled since 1987.”

According to the IMF, Mexico’s GDP grew by 83 percent over this period, which is pretty far from quadrupling. Honest newspapers correct their mistakes, but as the slogan at the Washington Post says, “lies in the service of giving more money to rich people are no vice.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This point is worth mentioning in the context of a comment by Esther L. George, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, to CNBC yesterday. Ms. George said:

“While we haven’t hit 2 percent, I’m reminded that 2 percent is a target over the long term, and in the context of a growing economy, of jobs being added, I don’t think it’s an issue that we should be particularly concerned about unless we see something change.”

Actually, the Fed’s stated policy is that 2 percent is a target as a long-term average. This means that the periods of below 2 percent inflation should be roughly offset by periods of above 2 percent inflation.

Most forecasts show the inflation rate remaining under 2 percent for at least the near term future. At some point, the economy will have another recession, during which the inflation rate is almost certain to fall. This means that if the inflation rate is just reaching 2.0 percent at the point the economy enters a recession, the Fed will have seriously undershot its stated target.

This point is worth mentioning in the context of a comment by Esther L. George, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, to CNBC yesterday. Ms. George said:

“While we haven’t hit 2 percent, I’m reminded that 2 percent is a target over the long term, and in the context of a growing economy, of jobs being added, I don’t think it’s an issue that we should be particularly concerned about unless we see something change.”

Actually, the Fed’s stated policy is that 2 percent is a target as a long-term average. This means that the periods of below 2 percent inflation should be roughly offset by periods of above 2 percent inflation.

Most forecasts show the inflation rate remaining under 2 percent for at least the near term future. At some point, the economy will have another recession, during which the inflation rate is almost certain to fall. This means that if the inflation rate is just reaching 2.0 percent at the point the economy enters a recession, the Fed will have seriously undershot its stated target.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión