Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Paul Krugman again went after Paul Ryan for the lack of specifics in his proposals for eliminating the national debt. As he reminds us, centrist commentators widely praised these proposals at the time as serious budget plans.

While Krugman is absolutely right on the tax side (Ryan says that he will offset lower tax rates by eliminating unspecified tax loopholes), he should give Ryan credit for what he actually proposes on the spending side. As I have pointed out elsewhere, Ryan has essentially proposed eliminating the federal government other than Social Security, Medicare and other health programs, and the military.

“This fact can be found in the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) analysis of Ryan’s budget (page 16, Table 2). The analysis shows Ryan’s budget shrinking everything other than Social Security and Medicare and other health care programs to 3.5 percent of GDP by 2050. This is roughly the current size of the military budget, which Ryan has indicated he wants to increase. That leaves zero for everything else.

“Included in everything else is the Justice Department, the National Park System, the State Department, the Department of Education, the Food and Drug Administration, Food Stamps, the National Institutes of Health, and just about everything else that the government does. Just to be clear, CBO did this analysis under Ryan’s supervision. He never indicated any displeasure with its assessment. In fact he boasted about the fact that CBO showed his budget paying off the national debt.”

So the Washington press corps favorite thoughtful conservative wants to get rid of almost the entire federal government. Let’s give Mr. Ryan credit for what he is proposing. It is specific, it just happens to be crazy.

Paul Krugman again went after Paul Ryan for the lack of specifics in his proposals for eliminating the national debt. As he reminds us, centrist commentators widely praised these proposals at the time as serious budget plans.

While Krugman is absolutely right on the tax side (Ryan says that he will offset lower tax rates by eliminating unspecified tax loopholes), he should give Ryan credit for what he actually proposes on the spending side. As I have pointed out elsewhere, Ryan has essentially proposed eliminating the federal government other than Social Security, Medicare and other health programs, and the military.

“This fact can be found in the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) analysis of Ryan’s budget (page 16, Table 2). The analysis shows Ryan’s budget shrinking everything other than Social Security and Medicare and other health care programs to 3.5 percent of GDP by 2050. This is roughly the current size of the military budget, which Ryan has indicated he wants to increase. That leaves zero for everything else.

“Included in everything else is the Justice Department, the National Park System, the State Department, the Department of Education, the Food and Drug Administration, Food Stamps, the National Institutes of Health, and just about everything else that the government does. Just to be clear, CBO did this analysis under Ryan’s supervision. He never indicated any displeasure with its assessment. In fact he boasted about the fact that CBO showed his budget paying off the national debt.”

So the Washington press corps favorite thoughtful conservative wants to get rid of almost the entire federal government. Let’s give Mr. Ryan credit for what he is proposing. It is specific, it just happens to be crazy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an interesting piece by Sheri Berman on the decline of the center-left in Europe. It points to the sharp drop in the support for social democratic parties across the continent, with many parties that used to lead government barely getting above 20 percent of the vote. Voters apparently see little reason to support these parties. A similar story could be told about the center-left in the United States, although the money they command may allow them to still control the Democratic Party.

To carry her observations a bit further, these center-left parties have been largely complicit in the policies that have redistributed income upward over the last four decades. Tony Blair in the U.K., Gerhard Schroeder, and Bill Clinton were all associated with policies that benefited the financial industry at the expense of the rest of society.

The center-left parties have all been supportive of longer and stronger patent and copyright monopolies, which give money to Bill Gates and other incredibly rich people, as well as more educated workers generally, at the expense of workers with less education who would provide the traditional base for center-left parties. These parties, especially the Democrats under Clinton, supported trade deals which were designed to redistribute income from less-educated workers to capital and the most highly educated workers.

And, these parties have generally supported fiscal and monetary policies that have had the effect of keeping unemployment high in order to minimize the risk of inflation. By reducing workers’ bargaining power, these policies have put downward pressure on the wages of the bulk of the workforce. (Yes, these points and more are covered in my [free] book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

Anyhow, it is not surprising that workers will not support political parties that are committed to taking money out of their pockets and giving it to the rich. If this continues to be the agenda of center-left parties, they are not likely to have much of a future.

The NYT had an interesting piece by Sheri Berman on the decline of the center-left in Europe. It points to the sharp drop in the support for social democratic parties across the continent, with many parties that used to lead government barely getting above 20 percent of the vote. Voters apparently see little reason to support these parties. A similar story could be told about the center-left in the United States, although the money they command may allow them to still control the Democratic Party.

To carry her observations a bit further, these center-left parties have been largely complicit in the policies that have redistributed income upward over the last four decades. Tony Blair in the U.K., Gerhard Schroeder, and Bill Clinton were all associated with policies that benefited the financial industry at the expense of the rest of society.

The center-left parties have all been supportive of longer and stronger patent and copyright monopolies, which give money to Bill Gates and other incredibly rich people, as well as more educated workers generally, at the expense of workers with less education who would provide the traditional base for center-left parties. These parties, especially the Democrats under Clinton, supported trade deals which were designed to redistribute income from less-educated workers to capital and the most highly educated workers.

And, these parties have generally supported fiscal and monetary policies that have had the effect of keeping unemployment high in order to minimize the risk of inflation. By reducing workers’ bargaining power, these policies have put downward pressure on the wages of the bulk of the workforce. (Yes, these points and more are covered in my [free] book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

Anyhow, it is not surprising that workers will not support political parties that are committed to taking money out of their pockets and giving it to the rich. If this continues to be the agenda of center-left parties, they are not likely to have much of a future.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A NYT article on the debate in Europe over regulating Uber and other “gig economy” companies raised the possibility that Uber may stop doing business in the United Kingdom if it was required to treat its workers as employees:

“If the ruling is upheld [that Uber workers are employees], it could hit the business model on which Uber, Deliveroo and similar online platforms rely. That may mean a major recalibration of the gig economy, or it may drive companies out of those countries which choose to impose stiffer regulation.

“Outside Europe, there have been signs of that happening: Uber threatened to leave Quebec this month if the government there pressed ahead with tougher standards for drivers.”

While the article implies that the departure of Uber would be a bad outcome for the people of the United Kingdom and Quebec there is no reason to think this is the case unless they happen to be large holders of Uber stock. There are plenty of other companies that apparently are better able to deal with regulations than Uber. They would presumably fill any gap created by Uber’s departure.

We saw this last year when Austin imposed a law requiring that drivers for services like Uber and Lyft be finger-printed, just like other taxi drivers. The two companies sponsored a ballot initiative in the city and spend a huge amount of money pushing their opposition to fingerprinting. They also threatened to leave if the initiative failed.

The initiative was defeated and both companies stopped serving the city. The gap created was quickly filled by a number of start-ups that apparently were able to deal with the fingerprinting requirement. (Uber then lobbied the Texas legislature to have the Austin rule overturned.) Anyhow, the prospect of Uber ending its operations in an area should be seen an opportunity for local start-ups, not a threat.

Note: An earlier version of this post said that Uber CEO Dara Koshrowshahi was on the board of the NYT. He resigned this position on September 7th.

A NYT article on the debate in Europe over regulating Uber and other “gig economy” companies raised the possibility that Uber may stop doing business in the United Kingdom if it was required to treat its workers as employees:

“If the ruling is upheld [that Uber workers are employees], it could hit the business model on which Uber, Deliveroo and similar online platforms rely. That may mean a major recalibration of the gig economy, or it may drive companies out of those countries which choose to impose stiffer regulation.

“Outside Europe, there have been signs of that happening: Uber threatened to leave Quebec this month if the government there pressed ahead with tougher standards for drivers.”

While the article implies that the departure of Uber would be a bad outcome for the people of the United Kingdom and Quebec there is no reason to think this is the case unless they happen to be large holders of Uber stock. There are plenty of other companies that apparently are better able to deal with regulations than Uber. They would presumably fill any gap created by Uber’s departure.

We saw this last year when Austin imposed a law requiring that drivers for services like Uber and Lyft be finger-printed, just like other taxi drivers. The two companies sponsored a ballot initiative in the city and spend a huge amount of money pushing their opposition to fingerprinting. They also threatened to leave if the initiative failed.

The initiative was defeated and both companies stopped serving the city. The gap created was quickly filled by a number of start-ups that apparently were able to deal with the fingerprinting requirement. (Uber then lobbied the Texas legislature to have the Austin rule overturned.) Anyhow, the prospect of Uber ending its operations in an area should be seen an opportunity for local start-ups, not a threat.

Note: An earlier version of this post said that Uber CEO Dara Koshrowshahi was on the board of the NYT. He resigned this position on September 7th.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This is in effect what they did when they criticized an analysis of the proposal by the non-partisan Tax Policy Center. An NYT article on the analysis, which showed the plan would lead to massive tax breaks for the wealthy and a large increase in the deficit, referred to the Republican response:

“Republicans quickly dismissed the analysis, saying the tax cut framework needs detail before it can be accurately assessed. A nine-page proposal for a tax overhaul, announced by Mr. Trump and Republican leaders in Congress on Wednesday, did not include income levels for its three personal income brackets. It left the door open to a fourth level of taxation for high-income taxpayers, and it did not specify the size of an enhanced child tax credit.

“‘This analysis is based on guesswork and biased assumptions designed to promote the authors’ point of view — rather actual detail from a bill that has not yet been written by the committees,’ said Antonia Ferrier, a spokeswoman for Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the majority leader.”

The claim that there is not yet enough information available to evaluate the plan is incredibly damning to the Republican leadership who crafted it. They spent months working on the plan. As their comment indicates, there are still important aspects of the plan that need to be filled in.

This should warrant a separate article telling readers what the Republicans were doing when they were supposed to be working on their tax plan. If the idea is that they will just decide major aspects of the tax plan in the last days before Congress votes (they plan to vote this fall) then it means they intend to put in place major changes in the U.S. tax code in a way that doesn’t allow for serious public debate. This fact deserves attention.

This is in effect what they did when they criticized an analysis of the proposal by the non-partisan Tax Policy Center. An NYT article on the analysis, which showed the plan would lead to massive tax breaks for the wealthy and a large increase in the deficit, referred to the Republican response:

“Republicans quickly dismissed the analysis, saying the tax cut framework needs detail before it can be accurately assessed. A nine-page proposal for a tax overhaul, announced by Mr. Trump and Republican leaders in Congress on Wednesday, did not include income levels for its three personal income brackets. It left the door open to a fourth level of taxation for high-income taxpayers, and it did not specify the size of an enhanced child tax credit.

“‘This analysis is based on guesswork and biased assumptions designed to promote the authors’ point of view — rather actual detail from a bill that has not yet been written by the committees,’ said Antonia Ferrier, a spokeswoman for Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the majority leader.”

The claim that there is not yet enough information available to evaluate the plan is incredibly damning to the Republican leadership who crafted it. They spent months working on the plan. As their comment indicates, there are still important aspects of the plan that need to be filled in.

This should warrant a separate article telling readers what the Republicans were doing when they were supposed to be working on their tax plan. If the idea is that they will just decide major aspects of the tax plan in the last days before Congress votes (they plan to vote this fall) then it means they intend to put in place major changes in the U.S. tax code in a way that doesn’t allow for serious public debate. This fact deserves attention.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

We know the NYT has to practice affirmative action for conservative columnists. Otherwise, they would never have any on their opinion pages, but they might have gone too far with Bret Stephens. The guy apparently knows literally nothing about the economy and is so ignorant he doesn’t even know how little he knows.

In his latest column he touts the good economic news under Donald Trump:

“The Dow keeps hitting record highs, and the economy is finally growing above the 3 percent mark.”

This is meant to say that things are going great for the country. The new highs in the stock market are good news for the roughly 25 percent of the country that holds substantial amounts of stock. For the rest of the country, they make less difference than the outcome of this Sunday’s football games.

As fans of Econ 101 know, the stock market is a measure of expected future profits, that is when it is not in a bubble driven by irrational exuberance. So the current expectation is that after-tax corporate profits will be a larger share of future income. That’s great news for large shareholders. And guess where those larger expected profits will come from? Are you celebrating yet?

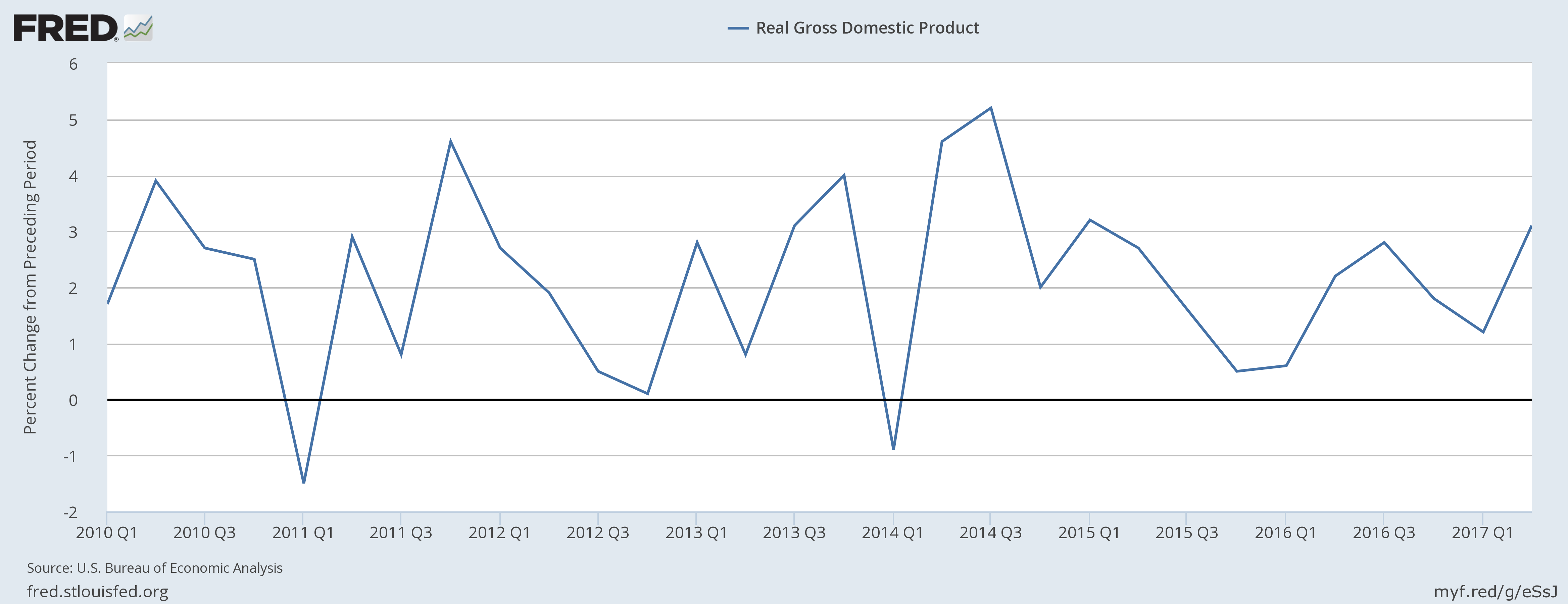

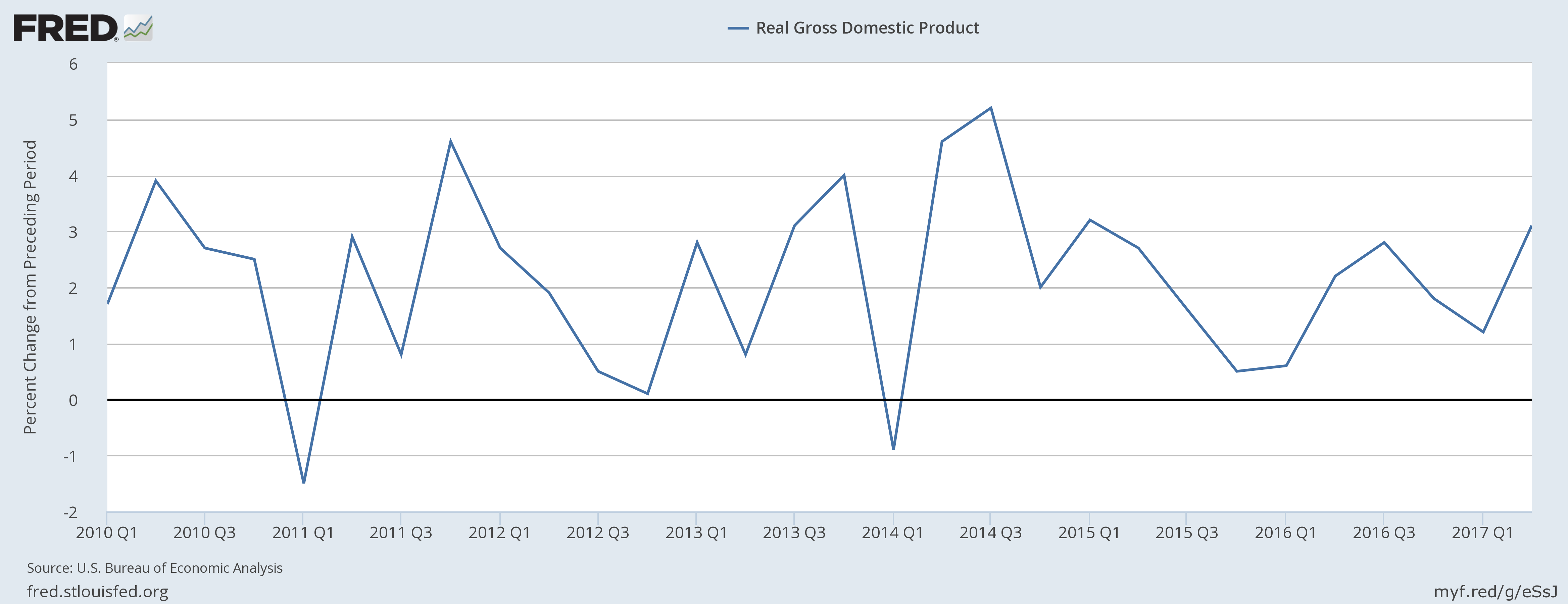

The second part of this sentence is perhaps even worse than the first part. “The economy is finally growing above the 3 percent mark.” No, the economy is not growing above the 3 percent mark, we had one quarter of growth above the 3.1 percent mark. We have had many quarters of growth above the 3.0 percent mark in this recovery.

Economic growth tends to fluctuate quarter by quarter. Those old enough to remember will recall that growth in the first quarter was just 1.2 percent. That explains part of the stronger growth in the current quarter, as weak sales of durable goods in the first quarter led to strong growth in sales in the second quarter.

Anyhow, Stephens apparently seems to think that the 3.1 percent growth in the second quarter implies that the economy is now on a growth path of above 3.0 percent. If there is any economist who agrees with this assessment, they are keeping a very low profile. For what it’s worth, the most recent projection for third quarter GDP, based on the data we have to date, is 2.3 percent.

Note: An earlier version put the 3.1 percent growth as being in the third quarter. This was reported GDP for the second quarter. Thanks to Boris Soroker.

We know the NYT has to practice affirmative action for conservative columnists. Otherwise, they would never have any on their opinion pages, but they might have gone too far with Bret Stephens. The guy apparently knows literally nothing about the economy and is so ignorant he doesn’t even know how little he knows.

In his latest column he touts the good economic news under Donald Trump:

“The Dow keeps hitting record highs, and the economy is finally growing above the 3 percent mark.”

This is meant to say that things are going great for the country. The new highs in the stock market are good news for the roughly 25 percent of the country that holds substantial amounts of stock. For the rest of the country, they make less difference than the outcome of this Sunday’s football games.

As fans of Econ 101 know, the stock market is a measure of expected future profits, that is when it is not in a bubble driven by irrational exuberance. So the current expectation is that after-tax corporate profits will be a larger share of future income. That’s great news for large shareholders. And guess where those larger expected profits will come from? Are you celebrating yet?

The second part of this sentence is perhaps even worse than the first part. “The economy is finally growing above the 3 percent mark.” No, the economy is not growing above the 3 percent mark, we had one quarter of growth above the 3.1 percent mark. We have had many quarters of growth above the 3.0 percent mark in this recovery.

Economic growth tends to fluctuate quarter by quarter. Those old enough to remember will recall that growth in the first quarter was just 1.2 percent. That explains part of the stronger growth in the current quarter, as weak sales of durable goods in the first quarter led to strong growth in sales in the second quarter.

Anyhow, Stephens apparently seems to think that the 3.1 percent growth in the second quarter implies that the economy is now on a growth path of above 3.0 percent. If there is any economist who agrees with this assessment, they are keeping a very low profile. For what it’s worth, the most recent projection for third quarter GDP, based on the data we have to date, is 2.3 percent.

Note: An earlier version put the 3.1 percent growth as being in the third quarter. This was reported GDP for the second quarter. Thanks to Boris Soroker.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In elite circles you are supposed to be for anything called a “free trade” agreement, otherwise, people will call you names. And names really hurt highly educated people. This is why most highly educated people supported the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), even though they had no clue what was in it. As NYT columnist Thomas Friedman famously said:

“I was speaking out in Minnesota — my hometown, in fact — and a guy stood up in the audience, said, ‘Mr. Friedman, is there any free trade agreement you’d oppose?’ I said, ‘No, absolutely not.’ I said, ‘You know what, sir? I wrote a column supporting the CAFTA, the Caribbean Free Trade initiative. I didn’t even know what was in it. I just knew two words: free trade.'”

The rationale given for the TPP has constantly shifted in response to the political climate. It was originally pushed for its economic benefits in terms of more growth and jobs. However, no serious analysis could show anything other than trivial benefits for the economy.

While removing trade barriers might generally be good for growth, there are relatively few barriers remaining between the United States and the other eleven countries in the TPP. It already has trade agreements with six of these countries.

In fact, the TPP actually increases protectionist barriers in the form of longer and stronger patent and copyright and related protections. For some reason, the economic analyses don’t include the negative effects of increasing these protections, even though their impact on the prices of the affected products, most importantly prescription drugs, dwarfs the impact of lowering a tariff of one or two percentage points to zero.

Since economics won’t sell the TPP, the alternative is to make it a geo-political pact, with the main target being China. The NYT goes this route with an article that tweaks Donald Trump for his opposition to the TPP.

“Faced with such an enemy, one might imagine the United States would gather allies in a concerted effort to contain China’s mercantilist ambitions. Except that Mr. Trump, in one of his earliest actions, revoked American participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a pact promoted by his predecessor as a means of doing precisely that. He walked away while extracting no discernible benefits from China.”

The main problem with seeing the TPP as a pact designed as a weapon against China is that it doesn’t seem to have been designed that way. Most obviously, the rules of origin (ROO) provisions, which determine which items can benefit from the preferential treatment provided by the TPP, are extremely weak. For example, the ROO in the TPP require originating content of between 45 percent and 55 percent for vehicles and engines and some other car parts. For most parts, the requirement is between 35 and 45 percent. These TPP ROO are considerably weaker than the ones in NAFTA, which required 62.5 percent content from the countries in the agreement.

This matters in reference to China since China is likely to be the main provider of inputs from countries outside the pact. This means that for some car parts, China can legally provide 65 percent of the value, and still get favorable treatment through the TPP. Given the ability of companies to fudge numbers presented to customs agents, we can envision the share of Chinese content rising to 70 or 75 percent, and still getting preferential treatment under the TPP. This doesn’t sound like a pact designed in opposition to China.

In elite circles you are supposed to be for anything called a “free trade” agreement, otherwise, people will call you names. And names really hurt highly educated people. This is why most highly educated people supported the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), even though they had no clue what was in it. As NYT columnist Thomas Friedman famously said:

“I was speaking out in Minnesota — my hometown, in fact — and a guy stood up in the audience, said, ‘Mr. Friedman, is there any free trade agreement you’d oppose?’ I said, ‘No, absolutely not.’ I said, ‘You know what, sir? I wrote a column supporting the CAFTA, the Caribbean Free Trade initiative. I didn’t even know what was in it. I just knew two words: free trade.'”

The rationale given for the TPP has constantly shifted in response to the political climate. It was originally pushed for its economic benefits in terms of more growth and jobs. However, no serious analysis could show anything other than trivial benefits for the economy.

While removing trade barriers might generally be good for growth, there are relatively few barriers remaining between the United States and the other eleven countries in the TPP. It already has trade agreements with six of these countries.

In fact, the TPP actually increases protectionist barriers in the form of longer and stronger patent and copyright and related protections. For some reason, the economic analyses don’t include the negative effects of increasing these protections, even though their impact on the prices of the affected products, most importantly prescription drugs, dwarfs the impact of lowering a tariff of one or two percentage points to zero.

Since economics won’t sell the TPP, the alternative is to make it a geo-political pact, with the main target being China. The NYT goes this route with an article that tweaks Donald Trump for his opposition to the TPP.

“Faced with such an enemy, one might imagine the United States would gather allies in a concerted effort to contain China’s mercantilist ambitions. Except that Mr. Trump, in one of his earliest actions, revoked American participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a pact promoted by his predecessor as a means of doing precisely that. He walked away while extracting no discernible benefits from China.”

The main problem with seeing the TPP as a pact designed as a weapon against China is that it doesn’t seem to have been designed that way. Most obviously, the rules of origin (ROO) provisions, which determine which items can benefit from the preferential treatment provided by the TPP, are extremely weak. For example, the ROO in the TPP require originating content of between 45 percent and 55 percent for vehicles and engines and some other car parts. For most parts, the requirement is between 35 and 45 percent. These TPP ROO are considerably weaker than the ones in NAFTA, which required 62.5 percent content from the countries in the agreement.

This matters in reference to China since China is likely to be the main provider of inputs from countries outside the pact. This means that for some car parts, China can legally provide 65 percent of the value, and still get favorable treatment through the TPP. Given the ability of companies to fudge numbers presented to customs agents, we can envision the share of Chinese content rising to 70 or 75 percent, and still getting preferential treatment under the TPP. This doesn’t sound like a pact designed in opposition to China.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Fed has been raising interest rates for the last 21 months with the idea that it wanted to slow growth in order to prevent inflation. It has now begun the process of selling off assets, which will also have the effect of raising interest rates and slowing growth.

While the need to slow growth is premised on the fear that inflation will rise to a higher than the desired rate, the data refuse to cooperate. The Bureau of Economic Analysis released data for the personal consumption expenditure deflator (PCE) this morning. The year over year rate of inflation in the core PCE, which is the focus of the Fed, fell to 1.3 percent, from 1.4 percent in July. (The annualized rate for the last three months compared to the prior three months was slightly higher at 1.4 percent.)

Anyhow, it is difficult to see any basis for the Fed’s concern that the inflation rate will exceed its target of a 2.0 percent average rate. At least for now, it is going in the wrong direction.

The Fed has been raising interest rates for the last 21 months with the idea that it wanted to slow growth in order to prevent inflation. It has now begun the process of selling off assets, which will also have the effect of raising interest rates and slowing growth.

While the need to slow growth is premised on the fear that inflation will rise to a higher than the desired rate, the data refuse to cooperate. The Bureau of Economic Analysis released data for the personal consumption expenditure deflator (PCE) this morning. The year over year rate of inflation in the core PCE, which is the focus of the Fed, fell to 1.3 percent, from 1.4 percent in July. (The annualized rate for the last three months compared to the prior three months was slightly higher at 1.4 percent.)

Anyhow, it is difficult to see any basis for the Fed’s concern that the inflation rate will exceed its target of a 2.0 percent average rate. At least for now, it is going in the wrong direction.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión