The Washington Post had a good piece pointing out the relatively small share of the population that would be hit by the cap of $500,000 on the amount of the principal for which interest is tax deductible. While it pointed out that a relatively small share of homes sell for a large enough amount to require a $500,000 mortgage and that the interest up to $500,000 will still be deductible, it neglected to point out that the principal dwindles over time so that even people who took out a mortgage of more than $500,000 will soon find that all their interest is still deductible.

For example, if someone takes out a $600,000, 30-year mortgage, after 7–8 years they will have paid off more than $100,000 of this mortgage so that all of their interest is again deductible. For mortgages over, but near, $500,000, it will only for the first years of a mortgage that a homeowner will be affected by this provision.

The Washington Post had a good piece pointing out the relatively small share of the population that would be hit by the cap of $500,000 on the amount of the principal for which interest is tax deductible. While it pointed out that a relatively small share of homes sell for a large enough amount to require a $500,000 mortgage and that the interest up to $500,000 will still be deductible, it neglected to point out that the principal dwindles over time so that even people who took out a mortgage of more than $500,000 will soon find that all their interest is still deductible.

For example, if someone takes out a $600,000, 30-year mortgage, after 7–8 years they will have paid off more than $100,000 of this mortgage so that all of their interest is again deductible. For mortgages over, but near, $500,000, it will only for the first years of a mortgage that a homeowner will be affected by this provision.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

An NYT article discussing the prospects of the Republican tax plan included projections from the Tax Foundation which does not indicate that it is a conservative organization. The piece told readers:

“When economic growth is taken into account, the gains would be more evenly distributed, with the middle class seeing the biggest income increase on a percentage basis. That is because the Tax Foundation assumes additional growth spurred by business tax cuts largely finds its way into workers’ paychecks.”

The growth assumed by the Tax Foundation in its projections is not assumed by independent analysts.

An NYT article discussing the prospects of the Republican tax plan included projections from the Tax Foundation which does not indicate that it is a conservative organization. The piece told readers:

“When economic growth is taken into account, the gains would be more evenly distributed, with the middle class seeing the biggest income increase on a percentage basis. That is because the Tax Foundation assumes additional growth spurred by business tax cuts largely finds its way into workers’ paychecks.”

The growth assumed by the Tax Foundation in its projections is not assumed by independent analysts.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

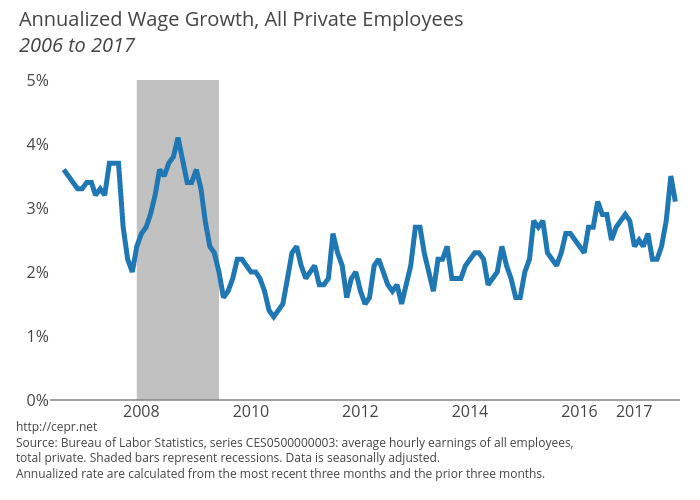

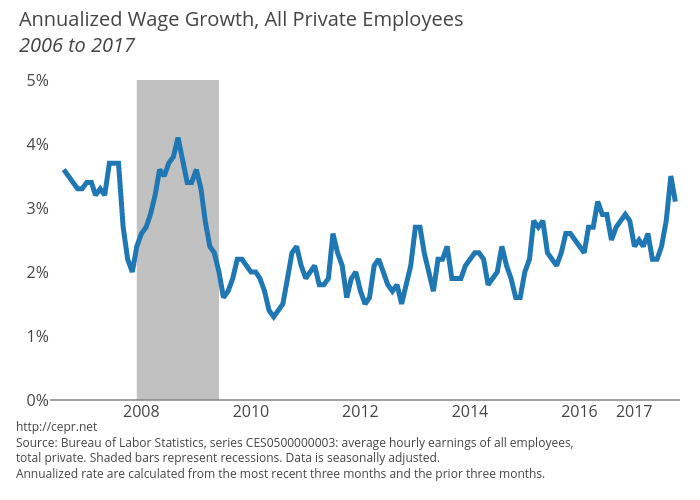

The jobs report for October showed the unemployment rate falling to 4.1 percent, the lowest rate in almost 17 years. Of course, as many have noted, the unemployment data are somewhat erratic and this was associated with a drop in employment rates (EPOPs), as people left the labor market, which is not good news. Still, the drop in EPOPs followed a jump in September, so that even with the October decline the EPOP for prime-age (ages 25 to 54) women is still 0.7 percentage points above its year-ago level and for men, the increase is 0.6 percentage points. So this is still a very good story.

But the other part of the story, that many folks seem to have missed, is that there is evidence of a modest uptick in wage growth. Typically we look at the year over year gain in wages, which is telling us much about wage growth last November as it is about the pace of wage growth last month. If we focus on the more recent data, taking the average hourly wage for the last three months (August to October) with the prior three months (May to July), there is clear evidence of an uptick in wage growth, as shown below.

The annualized wage growth by this measure is 3.1 percent. If we knock off a couple of tenths due to the fact that September’s number was distorted by the hurricane, we are still looking at a 2.9 percent rate of wage growth. While this is hardly spectacular, if inflation remains under 2.0 percent (it jumped in September due to higher gas prices caused by the hurricanes), it translates in a modest pace of real wage growth that is consistent with workers getting their share of productivity growth.

It would be good to see wages outpace productivity growth for a period of time in order to make back ground lost during the Great Recession, but it is important to note this progress. And, if the third quarter productivity number (3.0 percent growth) is not a fluke, then we can really talk about some good wage growth.

The jobs report for October showed the unemployment rate falling to 4.1 percent, the lowest rate in almost 17 years. Of course, as many have noted, the unemployment data are somewhat erratic and this was associated with a drop in employment rates (EPOPs), as people left the labor market, which is not good news. Still, the drop in EPOPs followed a jump in September, so that even with the October decline the EPOP for prime-age (ages 25 to 54) women is still 0.7 percentage points above its year-ago level and for men, the increase is 0.6 percentage points. So this is still a very good story.

But the other part of the story, that many folks seem to have missed, is that there is evidence of a modest uptick in wage growth. Typically we look at the year over year gain in wages, which is telling us much about wage growth last November as it is about the pace of wage growth last month. If we focus on the more recent data, taking the average hourly wage for the last three months (August to October) with the prior three months (May to July), there is clear evidence of an uptick in wage growth, as shown below.

The annualized wage growth by this measure is 3.1 percent. If we knock off a couple of tenths due to the fact that September’s number was distorted by the hurricane, we are still looking at a 2.9 percent rate of wage growth. While this is hardly spectacular, if inflation remains under 2.0 percent (it jumped in September due to higher gas prices caused by the hurricanes), it translates in a modest pace of real wage growth that is consistent with workers getting their share of productivity growth.

It would be good to see wages outpace productivity growth for a period of time in order to make back ground lost during the Great Recession, but it is important to note this progress. And, if the third quarter productivity number (3.0 percent growth) is not a fluke, then we can really talk about some good wage growth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There are many reasons to object to the Republican tax cut plan. Most importantly, the corporate tax cut is likely to primarily benefit shareholders, with little impact on investment; the elimination of the estate tax is a gift to the very richest people in the country; and the 25 percent tax rate for rich people on the income they receive from pass-through businesses is both a huge gift to the very rich and an enormous growth incentive for the tax shelter industry.

But one complaint is largely ill-founded. The limit of the mortgage interest to payments on $500,000 in principal is not likely to have much negative impact on middle-income households. While the NYT tells us that people buying “starter houses” in places like New York City and Silicon Valley are likely to be hit, this impact is likely to be minimal. This can be seen with a bit of arithmetic.

Ife we assume that someone buys a home with 10 percent down, then a $500,000 mortgage would go along with a house that sold for $555,000. According to the Case-Shiller indices, this would put you well into the top third of houses in the New York City commuter zone. (The cut-off is $480,000 in the most recent data.)

Furthermore, it is only the interest on the principle above this amount which is no longer tax deductible. Suppose someone has a $600,000 mortgage (enough to buy a $670,000 home, assuming a 90 percent loan to value ratio). They would be able to deduct the interest on $500,000 in principle, but not the last $100,000. If they paid a 4 percent interest rate on their loan, this would be $4,000 in lost deductions. If they are in the 25 percent bracket, this would amount to an increase of $1,000 in their taxes.

While this amount is not trivial since this person is paying $24,000 a year in mortgage interest alone (taxes and principle almost certainly raise housing costs above $40k a year), their income is almost certainly well over $100k a year, so this is not a moderate-income household. Furthermore, as the principal is paid down, a greater portion of the interest is tax deductible, as the outstanding principle falls to the $500,000 cutoff. In short, it does not make sense to claim this limit is a big hit to middle-income households, even in areas with high-priced housing.

There are many reasons to object to the Republican tax cut plan. Most importantly, the corporate tax cut is likely to primarily benefit shareholders, with little impact on investment; the elimination of the estate tax is a gift to the very richest people in the country; and the 25 percent tax rate for rich people on the income they receive from pass-through businesses is both a huge gift to the very rich and an enormous growth incentive for the tax shelter industry.

But one complaint is largely ill-founded. The limit of the mortgage interest to payments on $500,000 in principal is not likely to have much negative impact on middle-income households. While the NYT tells us that people buying “starter houses” in places like New York City and Silicon Valley are likely to be hit, this impact is likely to be minimal. This can be seen with a bit of arithmetic.

Ife we assume that someone buys a home with 10 percent down, then a $500,000 mortgage would go along with a house that sold for $555,000. According to the Case-Shiller indices, this would put you well into the top third of houses in the New York City commuter zone. (The cut-off is $480,000 in the most recent data.)

Furthermore, it is only the interest on the principle above this amount which is no longer tax deductible. Suppose someone has a $600,000 mortgage (enough to buy a $670,000 home, assuming a 90 percent loan to value ratio). They would be able to deduct the interest on $500,000 in principle, but not the last $100,000. If they paid a 4 percent interest rate on their loan, this would be $4,000 in lost deductions. If they are in the 25 percent bracket, this would amount to an increase of $1,000 in their taxes.

While this amount is not trivial since this person is paying $24,000 a year in mortgage interest alone (taxes and principle almost certainly raise housing costs above $40k a year), their income is almost certainly well over $100k a year, so this is not a moderate-income household. Furthermore, as the principal is paid down, a greater portion of the interest is tax deductible, as the outstanding principle falls to the $500,000 cutoff. In short, it does not make sense to claim this limit is a big hit to middle-income households, even in areas with high-priced housing.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post reported that Republicans in Congress are now considering making their tax cuts temporary, so as to reduce their cost over the 10-year budget horizon. The paper neglected to mention that this change would completely undermine the basis for the claim that the tax cut will lead to boom in investment and growth.

This alleged boom is the basis for both the claim that the average family would get $4,000 from the tax cut and that additional growth would generate $1.5 trillion in revenue over the next decade. As I pointed out yesterday, the projection of an investment boom was never very plausible in any case, but for it to make any sense at all, the tax cuts have to be permanent.

The Republicans’ argument was that lower tax rates would increase the incentive for companies to invest. But if companies anticipate that the tax rate will return to its current level after a relatively short period of time, then the tax cut will provide little incentive. This means there is no basis for the assumption of a boom.

In the case of a temporary tax cut, the claim that average families will see a $4,000 dividend from higher pay makes no sense. And the claim of a $1.5 trillion growth dividend can be seen for what it is: a number snatched out of the air to claim the tax cut won’t increase the deficit.

The Washington Post reported that Republicans in Congress are now considering making their tax cuts temporary, so as to reduce their cost over the 10-year budget horizon. The paper neglected to mention that this change would completely undermine the basis for the claim that the tax cut will lead to boom in investment and growth.

This alleged boom is the basis for both the claim that the average family would get $4,000 from the tax cut and that additional growth would generate $1.5 trillion in revenue over the next decade. As I pointed out yesterday, the projection of an investment boom was never very plausible in any case, but for it to make any sense at all, the tax cuts have to be permanent.

The Republicans’ argument was that lower tax rates would increase the incentive for companies to invest. But if companies anticipate that the tax rate will return to its current level after a relatively short period of time, then the tax cut will provide little incentive. This means there is no basis for the assumption of a boom.

In the case of a temporary tax cut, the claim that average families will see a $4,000 dividend from higher pay makes no sense. And the claim of a $1.5 trillion growth dividend can be seen for what it is: a number snatched out of the air to claim the tax cut won’t increase the deficit.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A NYT article reported on a commitment by its president, Xi Jinping, to raise everyone in China above its official poverty level of 95 cents a day by 2020. According to the piece, 43 million people in China now fall under this income level.

While the piece implies this would be a difficult target for China to make, the cost would actually be quite small relative to the size of its economy. If it were to hand this amount of money (95 cents a day) to each of these 43 million people, it would cost the country $14.9 billion annually. This is just over 0.05 percent of its projected GDP for 2020 of $29.6 trillion. This target would still leave these and many other people very poor but if this is what China’s government is shooting for, there is little reason to think it will not be able to meet the target.

The article also says that China’s slowing growth will make reducing poverty more difficult. While it is harder to reduce poverty with slower growth rather than faster growth, China’s economy is still projected to be growing at more than a 6.0 percent annual rate, which is faster than almost every other country in the world.

A NYT article reported on a commitment by its president, Xi Jinping, to raise everyone in China above its official poverty level of 95 cents a day by 2020. According to the piece, 43 million people in China now fall under this income level.

While the piece implies this would be a difficult target for China to make, the cost would actually be quite small relative to the size of its economy. If it were to hand this amount of money (95 cents a day) to each of these 43 million people, it would cost the country $14.9 billion annually. This is just over 0.05 percent of its projected GDP for 2020 of $29.6 trillion. This target would still leave these and many other people very poor but if this is what China’s government is shooting for, there is little reason to think it will not be able to meet the target.

The article also says that China’s slowing growth will make reducing poverty more difficult. While it is harder to reduce poverty with slower growth rather than faster growth, China’s economy is still projected to be growing at more than a 6.0 percent annual rate, which is faster than almost every other country in the world.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post told readers that the Republican tax plan:

“…will aim to slash corporate tax rates, simplify taxes for individuals and families and lure the foreign operations of multinational firms back to the United States with incentives and penalties.”

While there is no plan at the moment, the reports to date have said the Republicans want to shift to a territorial tax under which companies don’t pay U.S. tax on their foreign profits. If this is true, their proposal will increase the incentive to shift operations overseas, or at least to have their profits appear to come from overseas operations.

It is worth noting that the concern expressed about future deficits in this piece is referring to a largely meaningless concept. If we are concerned about the commitment to future debt service payments then we should be looking at debt service payments, which are now near historic lows relative to the size of the economy.

We should also be asking about the burden the government creates by granting patent and copyright monopolies. This presently comes to close to $370 billion annually (more than twice the debt service burden) in the case of prescription drugs alone. This is the gap between what we pay for drugs, currently around $450 billion a year, and the price that would exist in a free market without patents and related protections, which would likely be less than $80 billion. The full cost of these protections in all areas is almost certainly at least twice the cost incurred in prescription drugs.

The Washington Post told readers that the Republican tax plan:

“…will aim to slash corporate tax rates, simplify taxes for individuals and families and lure the foreign operations of multinational firms back to the United States with incentives and penalties.”

While there is no plan at the moment, the reports to date have said the Republicans want to shift to a territorial tax under which companies don’t pay U.S. tax on their foreign profits. If this is true, their proposal will increase the incentive to shift operations overseas, or at least to have their profits appear to come from overseas operations.

It is worth noting that the concern expressed about future deficits in this piece is referring to a largely meaningless concept. If we are concerned about the commitment to future debt service payments then we should be looking at debt service payments, which are now near historic lows relative to the size of the economy.

We should also be asking about the burden the government creates by granting patent and copyright monopolies. This presently comes to close to $370 billion annually (more than twice the debt service burden) in the case of prescription drugs alone. This is the gap between what we pay for drugs, currently around $450 billion a year, and the price that would exist in a free market without patents and related protections, which would likely be less than $80 billion. The full cost of these protections in all areas is almost certainly at least twice the cost incurred in prescription drugs.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Republicans are telling us that cutting in the corporate tax rate will lead to a big $4000 pay increase for ordinary workers. The story goes that lower taxes will lead to a flood of new investment. This will increase productivity and higher productivity will be passed on to workers in higher wages.

That’s a nice story, but the data refuse to go along. My friend Josh Bivens took a quick look at the relationship across countries between corporate tax rates and the capital-to-labor ratio. If the investment boom story is true, then countries with the lowest corporate tax rate would have the highest capital-to-labor ratio.

Josh found the opposite. The countries with the highest capital-to-labor ratios actually had higher corporate tax rates on average than countries with lower capital-to-labor ratios. While no one would try to claim based on this evidence that raising the corporate tax rate would lead to more investment, it certainly is hard to reconcile this one with the Republicans’ story.

Just to consider all the possibilities. Josh looked to see if there was a relationship between the change in the tax rate and change in the capital-to-labor ratio. Here, also, the story goes the wrong way. The countries with the largest cuts in corporate tax rates had the smallest increase in their capital-to-labor ratios.

The implication of this simple analysis is that there is no reason to believe that cuts in the corporate tax rate will have any major impact on investment. It will simply mean more money in the pockets of shareholders, with little if any gain for ordinary workers. The moral here is that workers best not go out and spend their promised $4,000 tax cut dividend just yet.

The Republicans are telling us that cutting in the corporate tax rate will lead to a big $4000 pay increase for ordinary workers. The story goes that lower taxes will lead to a flood of new investment. This will increase productivity and higher productivity will be passed on to workers in higher wages.

That’s a nice story, but the data refuse to go along. My friend Josh Bivens took a quick look at the relationship across countries between corporate tax rates and the capital-to-labor ratio. If the investment boom story is true, then countries with the lowest corporate tax rate would have the highest capital-to-labor ratio.

Josh found the opposite. The countries with the highest capital-to-labor ratios actually had higher corporate tax rates on average than countries with lower capital-to-labor ratios. While no one would try to claim based on this evidence that raising the corporate tax rate would lead to more investment, it certainly is hard to reconcile this one with the Republicans’ story.

Just to consider all the possibilities. Josh looked to see if there was a relationship between the change in the tax rate and change in the capital-to-labor ratio. Here, also, the story goes the wrong way. The countries with the largest cuts in corporate tax rates had the smallest increase in their capital-to-labor ratios.

The implication of this simple analysis is that there is no reason to believe that cuts in the corporate tax rate will have any major impact on investment. It will simply mean more money in the pockets of shareholders, with little if any gain for ordinary workers. The moral here is that workers best not go out and spend their promised $4,000 tax cut dividend just yet.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a very informative piece on the prospects for the labor market changes being pushed through in France by its new president Emmanuel Macron. While the background explaining the proposed changes and their rationale was useful, the article included one important item that is seriously misleading. It said that nearly one in four young people in France is unemployed.

This figure is referring to the unemployment rate for French youth (ages 15–24), which the OECD reports as 24.6 percent. However, this figure is the percent of the labor force who are unemployed, not the percent of the population. The labor force is defined as people who are either employed or report to be looking for work and are therefore classified as unemployed.

In France, many fewer young people work than in the United States because higher education is largely free and students get stipends from the government. As a result, the employment rate for French youth is 28.3 percent, compared to 50.1 percent for the United States. If we look at unemployment as a share of the total youth population, the 8.7 percent rate in France is not hugely higher than the 5.8 percent rate in the United States.

Youth unemployment is still a serious issue in France (as it is the United States), but not quite as serious as the one in four figure may lead people to believe.

The NYT had a very informative piece on the prospects for the labor market changes being pushed through in France by its new president Emmanuel Macron. While the background explaining the proposed changes and their rationale was useful, the article included one important item that is seriously misleading. It said that nearly one in four young people in France is unemployed.

This figure is referring to the unemployment rate for French youth (ages 15–24), which the OECD reports as 24.6 percent. However, this figure is the percent of the labor force who are unemployed, not the percent of the population. The labor force is defined as people who are either employed or report to be looking for work and are therefore classified as unemployed.

In France, many fewer young people work than in the United States because higher education is largely free and students get stipends from the government. As a result, the employment rate for French youth is 28.3 percent, compared to 50.1 percent for the United States. If we look at unemployment as a share of the total youth population, the 8.7 percent rate in France is not hugely higher than the 5.8 percent rate in the United States.

Youth unemployment is still a serious issue in France (as it is the United States), but not quite as serious as the one in four figure may lead people to believe.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión