A front page Washington Post article on the continued use of coal in Germany, in spite of its impact on global warming, told readers that one of the reasons it is difficult to cut back on coal is the industry employs about 20,000 people. Since most readers are unlikely to have a clear idea of the size of Germany’s labor force, it would have been helpful to point out that this comes to less than 0.05 percent of its workforce of 43.0 million.

This doesn’t mean that job loss for these workers would not still be traumatic, although Germany does provide much better unemployment benefits than the United States. It is important for readers to have some sense of how important employment in the sector is to the nation as a whole, which this piece did not give.

A front page Washington Post article on the continued use of coal in Germany, in spite of its impact on global warming, told readers that one of the reasons it is difficult to cut back on coal is the industry employs about 20,000 people. Since most readers are unlikely to have a clear idea of the size of Germany’s labor force, it would have been helpful to point out that this comes to less than 0.05 percent of its workforce of 43.0 million.

This doesn’t mean that job loss for these workers would not still be traumatic, although Germany does provide much better unemployment benefits than the United States. It is important for readers to have some sense of how important employment in the sector is to the nation as a whole, which this piece did not give.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post refuses to follow journalistic norms and maintain a separation between the news and editorial pages when it comes to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Yet again the paper referred to the pact as a “free-trade” agreement.

Of course, the deal is not a free trade pact. It does little, if anything, to remove the barriers that protect highly paid professionals like doctors from international competition. Also, a major focus of the pact is longer and stronger patent and copyright protections.

These forms of protectionism have been a major factor in the upward redistribution of the last four decades. In the case of prescription drugs alone these protections add more than $370 billion annually (almost 2 percent of GDP) to what we spend on drugs. The Post supports these protections and apparently would like its readers to believe that they are somehow part of a free market.

The Washington Post refuses to follow journalistic norms and maintain a separation between the news and editorial pages when it comes to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Yet again the paper referred to the pact as a “free-trade” agreement.

Of course, the deal is not a free trade pact. It does little, if anything, to remove the barriers that protect highly paid professionals like doctors from international competition. Also, a major focus of the pact is longer and stronger patent and copyright protections.

These forms of protectionism have been a major factor in the upward redistribution of the last four decades. In the case of prescription drugs alone these protections add more than $370 billion annually (almost 2 percent of GDP) to what we spend on drugs. The Post supports these protections and apparently would like its readers to believe that they are somehow part of a free market.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That is effectively what he said when according to the Washington Post he claimed that “he has spoken to his own accountant about the tax plan and that he would be a ‘big loser’ if the deal is approved as written.” Of course, we don’t know exactly what Mr. Trump’s tax returns look like since he lied about releasing them once an audit was completed, but based on the one return that was made public, the plan looks like it was written to reduce his tax liability.

It reduces the tax rate for high-income people on income from pass-through corporations, which was pretty much all of Trump’s income on his return. It also eliminates the alternative minimum tax, which Trump had to pay for 2005. And it eliminates the estate tax, which Trump’s estate would almost certainly have to pay when he dies. In addition, it leaves in place a number of special tax breaks for the real estate sector, even as it eliminates them for other businesses.

It seems likely that either Mr. Trump’s accountant is incompetent or Trump lied about what they told him about the impact of the tax plan on his finances.

That is effectively what he said when according to the Washington Post he claimed that “he has spoken to his own accountant about the tax plan and that he would be a ‘big loser’ if the deal is approved as written.” Of course, we don’t know exactly what Mr. Trump’s tax returns look like since he lied about releasing them once an audit was completed, but based on the one return that was made public, the plan looks like it was written to reduce his tax liability.

It reduces the tax rate for high-income people on income from pass-through corporations, which was pretty much all of Trump’s income on his return. It also eliminates the alternative minimum tax, which Trump had to pay for 2005. And it eliminates the estate tax, which Trump’s estate would almost certainly have to pay when he dies. In addition, it leaves in place a number of special tax breaks for the real estate sector, even as it eliminates them for other businesses.

It seems likely that either Mr. Trump’s accountant is incompetent or Trump lied about what they told him about the impact of the tax plan on his finances.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Paul Krugman had an interesting blog post today on the impact of the Republican proposal to cut the corporate income tax. While he rejected the growth claims of the Trump administration, he noted the projections of the Penn-Wharton model that the tax cuts would increase GDP between 0.3 to 0.8 percent by 2027. He described this increase as “basically an invisible effect against background noise.”

This is worth comparing with the projected gains from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The very pro-TPP Peterson Institute projected gains of 0.5 percent of GDP by 2032. The United States International Trade Commission projected an increase in GNI (Gross National Income) of 0.23 percent by 2032. (Neither of these analyses tried to incorporate the impact of the increased protectionism in the TPP in the form of longer and stronger patent and copyright protections.)

Anyhow, if we agree with Krugman that the projected 0.3–0.8 percent of GDP gain from the cut in the corporate income tax is “basically an invisible effect against background noise,” then we can’t think the smaller and more distant projected gains from the TPP are a big deal, unless we are dishonest. (For the record, Krugman is not a guilty party here since he opposed the TPP.)

Paul Krugman had an interesting blog post today on the impact of the Republican proposal to cut the corporate income tax. While he rejected the growth claims of the Trump administration, he noted the projections of the Penn-Wharton model that the tax cuts would increase GDP between 0.3 to 0.8 percent by 2027. He described this increase as “basically an invisible effect against background noise.”

This is worth comparing with the projected gains from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The very pro-TPP Peterson Institute projected gains of 0.5 percent of GDP by 2032. The United States International Trade Commission projected an increase in GNI (Gross National Income) of 0.23 percent by 2032. (Neither of these analyses tried to incorporate the impact of the increased protectionism in the TPP in the form of longer and stronger patent and copyright protections.)

Anyhow, if we agree with Krugman that the projected 0.3–0.8 percent of GDP gain from the cut in the corporate income tax is “basically an invisible effect against background noise,” then we can’t think the smaller and more distant projected gains from the TPP are a big deal, unless we are dishonest. (For the record, Krugman is not a guilty party here since he opposed the TPP.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s hard to know what is the most cynical part of a tax bill designed to give as much money as possible to Donald Trump and his family, but the elimination of the tax deduction for medical expenses has to rate pretty high on the list. The Post had a good piece on the issue, pointing out how the loss of this deduction will make life considerably more difficult for a couple dealing with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

This case is perhaps somewhat extreme, but it is the sort of situation in which families would be in a position to benefit from the tax deduction. It only applies to expenses in excess of 10 percent of a family’s income, so it is only people with large expenses who would be in a situation to benefit from this deduction. Eliminating this deduction is likely to be a considerable financial hardship for families dealing with serious medical conditions.

It’s hard to know what is the most cynical part of a tax bill designed to give as much money as possible to Donald Trump and his family, but the elimination of the tax deduction for medical expenses has to rate pretty high on the list. The Post had a good piece on the issue, pointing out how the loss of this deduction will make life considerably more difficult for a couple dealing with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

This case is perhaps somewhat extreme, but it is the sort of situation in which families would be in a position to benefit from the tax deduction. It only applies to expenses in excess of 10 percent of a family’s income, so it is only people with large expenses who would be in a situation to benefit from this deduction. Eliminating this deduction is likely to be a considerable financial hardship for families dealing with serious medical conditions.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had a good piece pointing out the relatively small share of the population that would be hit by the cap of $500,000 on the amount of the principal for which interest is tax deductible. While it pointed out that a relatively small share of homes sell for a large enough amount to require a $500,000 mortgage and that the interest up to $500,000 will still be deductible, it neglected to point out that the principal dwindles over time so that even people who took out a mortgage of more than $500,000 will soon find that all their interest is still deductible.

For example, if someone takes out a $600,000, 30-year mortgage, after 7–8 years they will have paid off more than $100,000 of this mortgage so that all of their interest is again deductible. For mortgages over, but near, $500,000, it will only for the first years of a mortgage that a homeowner will be affected by this provision.

The Washington Post had a good piece pointing out the relatively small share of the population that would be hit by the cap of $500,000 on the amount of the principal for which interest is tax deductible. While it pointed out that a relatively small share of homes sell for a large enough amount to require a $500,000 mortgage and that the interest up to $500,000 will still be deductible, it neglected to point out that the principal dwindles over time so that even people who took out a mortgage of more than $500,000 will soon find that all their interest is still deductible.

For example, if someone takes out a $600,000, 30-year mortgage, after 7–8 years they will have paid off more than $100,000 of this mortgage so that all of their interest is again deductible. For mortgages over, but near, $500,000, it will only for the first years of a mortgage that a homeowner will be affected by this provision.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

An NYT article discussing the prospects of the Republican tax plan included projections from the Tax Foundation which does not indicate that it is a conservative organization. The piece told readers:

“When economic growth is taken into account, the gains would be more evenly distributed, with the middle class seeing the biggest income increase on a percentage basis. That is because the Tax Foundation assumes additional growth spurred by business tax cuts largely finds its way into workers’ paychecks.”

The growth assumed by the Tax Foundation in its projections is not assumed by independent analysts.

An NYT article discussing the prospects of the Republican tax plan included projections from the Tax Foundation which does not indicate that it is a conservative organization. The piece told readers:

“When economic growth is taken into account, the gains would be more evenly distributed, with the middle class seeing the biggest income increase on a percentage basis. That is because the Tax Foundation assumes additional growth spurred by business tax cuts largely finds its way into workers’ paychecks.”

The growth assumed by the Tax Foundation in its projections is not assumed by independent analysts.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

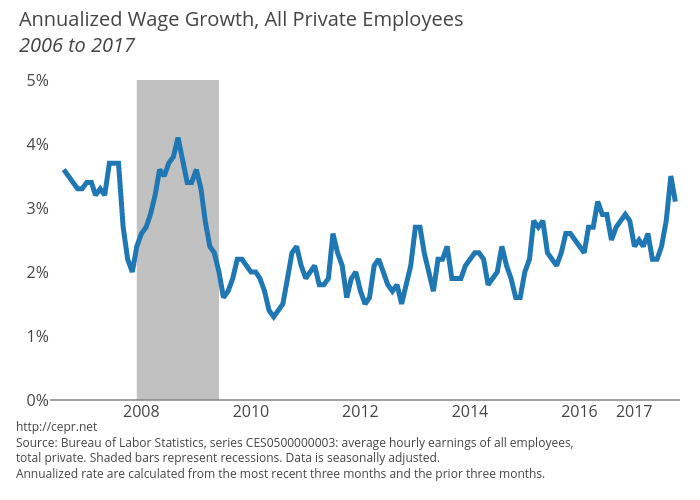

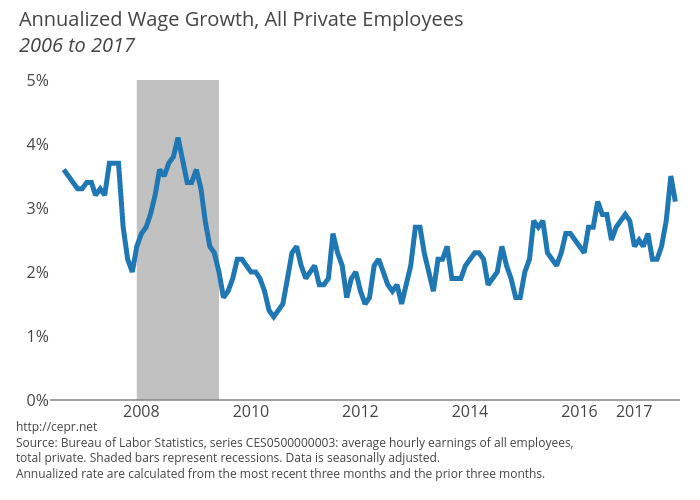

The jobs report for October showed the unemployment rate falling to 4.1 percent, the lowest rate in almost 17 years. Of course, as many have noted, the unemployment data are somewhat erratic and this was associated with a drop in employment rates (EPOPs), as people left the labor market, which is not good news. Still, the drop in EPOPs followed a jump in September, so that even with the October decline the EPOP for prime-age (ages 25 to 54) women is still 0.7 percentage points above its year-ago level and for men, the increase is 0.6 percentage points. So this is still a very good story.

But the other part of the story, that many folks seem to have missed, is that there is evidence of a modest uptick in wage growth. Typically we look at the year over year gain in wages, which is telling us much about wage growth last November as it is about the pace of wage growth last month. If we focus on the more recent data, taking the average hourly wage for the last three months (August to October) with the prior three months (May to July), there is clear evidence of an uptick in wage growth, as shown below.

The annualized wage growth by this measure is 3.1 percent. If we knock off a couple of tenths due to the fact that September’s number was distorted by the hurricane, we are still looking at a 2.9 percent rate of wage growth. While this is hardly spectacular, if inflation remains under 2.0 percent (it jumped in September due to higher gas prices caused by the hurricanes), it translates in a modest pace of real wage growth that is consistent with workers getting their share of productivity growth.

It would be good to see wages outpace productivity growth for a period of time in order to make back ground lost during the Great Recession, but it is important to note this progress. And, if the third quarter productivity number (3.0 percent growth) is not a fluke, then we can really talk about some good wage growth.

The jobs report for October showed the unemployment rate falling to 4.1 percent, the lowest rate in almost 17 years. Of course, as many have noted, the unemployment data are somewhat erratic and this was associated with a drop in employment rates (EPOPs), as people left the labor market, which is not good news. Still, the drop in EPOPs followed a jump in September, so that even with the October decline the EPOP for prime-age (ages 25 to 54) women is still 0.7 percentage points above its year-ago level and for men, the increase is 0.6 percentage points. So this is still a very good story.

But the other part of the story, that many folks seem to have missed, is that there is evidence of a modest uptick in wage growth. Typically we look at the year over year gain in wages, which is telling us much about wage growth last November as it is about the pace of wage growth last month. If we focus on the more recent data, taking the average hourly wage for the last three months (August to October) with the prior three months (May to July), there is clear evidence of an uptick in wage growth, as shown below.

The annualized wage growth by this measure is 3.1 percent. If we knock off a couple of tenths due to the fact that September’s number was distorted by the hurricane, we are still looking at a 2.9 percent rate of wage growth. While this is hardly spectacular, if inflation remains under 2.0 percent (it jumped in September due to higher gas prices caused by the hurricanes), it translates in a modest pace of real wage growth that is consistent with workers getting their share of productivity growth.

It would be good to see wages outpace productivity growth for a period of time in order to make back ground lost during the Great Recession, but it is important to note this progress. And, if the third quarter productivity number (3.0 percent growth) is not a fluke, then we can really talk about some good wage growth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión