There is a lot of craziness in the era of Trump. According to the Washington Post, a tax bill that gives the overwhelming majority of its benefits to the richest people in the country had “working-class roots.” This is pretty loony stuff.

There is a lot of craziness in the era of Trump. According to the Washington Post, a tax bill that gives the overwhelming majority of its benefits to the richest people in the country had “working-class roots.” This is pretty loony stuff.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

An NYT article on the winners and losers from the bill listed among the losers people who buy individual insurance, since it will leave insurers “stuck with more people who are older and ailing.” The issue here is ailing, not older. The exchanges can already charge different prices based on their age. While the law limits the band between age groups, so it’s not exactly equal to the difference in costs, this is a relatively small matter. The health of the people within an age group makes far more difference.

It is also important to note that many of the people who are predicted to go uninsured because of the repeal of the mandate are people who would have otherwise gotten Medicaid. These are people who would effectively get free insurance if they applied on the exchanges but won’t make the effort without the mandate.

An NYT article on the winners and losers from the bill listed among the losers people who buy individual insurance, since it will leave insurers “stuck with more people who are older and ailing.” The issue here is ailing, not older. The exchanges can already charge different prices based on their age. While the law limits the band between age groups, so it’s not exactly equal to the difference in costs, this is a relatively small matter. The health of the people within an age group makes far more difference.

It is also important to note that many of the people who are predicted to go uninsured because of the repeal of the mandate are people who would have otherwise gotten Medicaid. These are people who would effectively get free insurance if they applied on the exchanges but won’t make the effort without the mandate.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

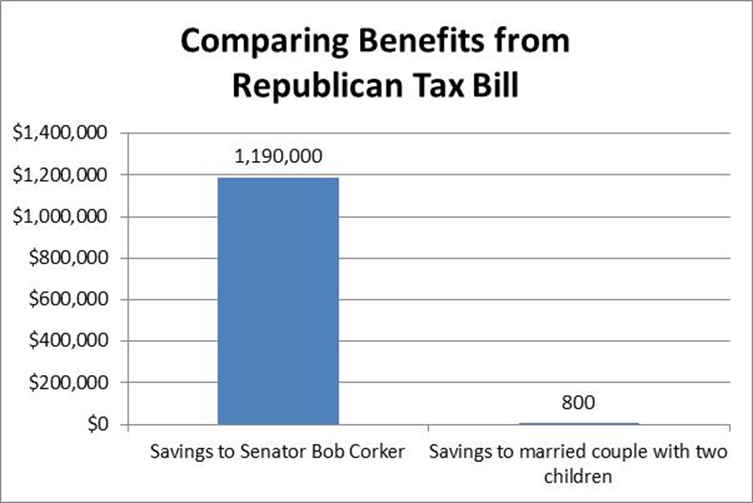

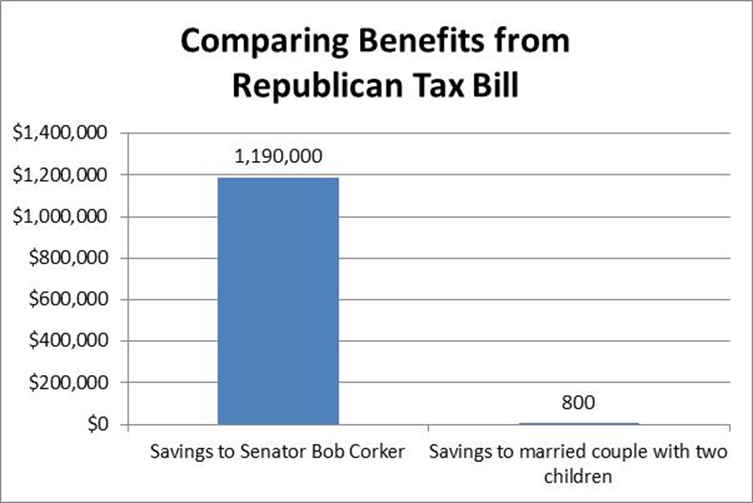

David Sirota, Josh Keefe, and Alex Kotch, writing at International Business Times, reported that a provision inserted into the Republican tax bill will provide large benefits to former holdout Senator Bob Corker, as well as President Trump. The provision would allow income from real estate investment trusts to be taxed at a 20 percent rate, as opposed to the 37 percent tax rate paid by high income individuals.

According to Corker’s disclosure forms, he makes between $1.2 million and $7.0 million annually in this sort of income. (We don’t know how much Donald Trump earns in this type of income since he broke his campaign promise about releasing his tax returns after his audit was completed.) If we plug in the top end $7 million figure, Corker could be saving as much as $1,190,000 from this late addition to the tax bill.

By comparison, much has been made of Senator Marco Rubio’s effort to change the refundability rules on the child tax credit, thereby giving more money to moderate-income families. According to calculations by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, with this change, a married couple with two children, earning $30,000 a year, will get back an additional $800 a year.

Source: International Business Times and Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

David Sirota, Josh Keefe, and Alex Kotch, writing at International Business Times, reported that a provision inserted into the Republican tax bill will provide large benefits to former holdout Senator Bob Corker, as well as President Trump. The provision would allow income from real estate investment trusts to be taxed at a 20 percent rate, as opposed to the 37 percent tax rate paid by high income individuals.

According to Corker’s disclosure forms, he makes between $1.2 million and $7.0 million annually in this sort of income. (We don’t know how much Donald Trump earns in this type of income since he broke his campaign promise about releasing his tax returns after his audit was completed.) If we plug in the top end $7 million figure, Corker could be saving as much as $1,190,000 from this late addition to the tax bill.

By comparison, much has been made of Senator Marco Rubio’s effort to change the refundability rules on the child tax credit, thereby giving more money to moderate-income families. According to calculations by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, with this change, a married couple with two children, earning $30,000 a year, will get back an additional $800 a year.

Source: International Business Times and Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is common to look at the ratio of new hires to job openings to get a sense of the tightness of the labor market. The idea is that if there is a high ratio of hires to openings, employers are not having trouble finding workers, whereas a low ratio means that jobs are going unfilled. This means either that employers are unable to find qualified workers, or that they are not willing to offer the market wage for some reason.

The Post had an article about the Trump administration’s plans to reduce the pay and benefits for federal government employees. It notes the arguments of Trump administration economists that federal employees are overpaid. It is worth noting that the ratio of hiring to openings in the federal government is far lower than in the pre-recession period.

The table below shows this ratio for several major sectors in the first six months of 2007 compared with the most recent six months.

| Ratio of Hires to Job Openings | |||||

| Jan-June ’07 | May-Oct ’17 | ||||

| Total Private | 1.16 | 0.93 | |||

| Retail | 1.78 | 1.08 | |||

| Accomodation and Food Service | 1.59 | 1.13 | |||

| Private minus retail &food service | 1.02 | 0.87 | |||

| Health Care & Social Assistance | 0.67 | 0.54 | |||

| Federal Government | 1.61 | 0.42 | |||

| S&L Education | 1.13 | 0.92 | |||

| S&L Other | 0.57 | 0.55 | |||

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen the ratio of hiring to openings is just over one quarter of its pre-recession level. This suggests that the federal government is already having a difficult time getting qualified workers given current pay and benefit packages. If it reduces pay and benefits further, then the federal government will presumably have an even more difficult time attracting qualified workers.

It is common to look at the ratio of new hires to job openings to get a sense of the tightness of the labor market. The idea is that if there is a high ratio of hires to openings, employers are not having trouble finding workers, whereas a low ratio means that jobs are going unfilled. This means either that employers are unable to find qualified workers, or that they are not willing to offer the market wage for some reason.

The Post had an article about the Trump administration’s plans to reduce the pay and benefits for federal government employees. It notes the arguments of Trump administration economists that federal employees are overpaid. It is worth noting that the ratio of hiring to openings in the federal government is far lower than in the pre-recession period.

The table below shows this ratio for several major sectors in the first six months of 2007 compared with the most recent six months.

| Ratio of Hires to Job Openings | |||||

| Jan-June ’07 | May-Oct ’17 | ||||

| Total Private | 1.16 | 0.93 | |||

| Retail | 1.78 | 1.08 | |||

| Accomodation and Food Service | 1.59 | 1.13 | |||

| Private minus retail &food service | 1.02 | 0.87 | |||

| Health Care & Social Assistance | 0.67 | 0.54 | |||

| Federal Government | 1.61 | 0.42 | |||

| S&L Education | 1.13 | 0.92 | |||

| S&L Other | 0.57 | 0.55 | |||

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen the ratio of hiring to openings is just over one quarter of its pre-recession level. This suggests that the federal government is already having a difficult time getting qualified workers given current pay and benefit packages. If it reduces pay and benefits further, then the federal government will presumably have an even more difficult time attracting qualified workers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Everyone remembers Marco Rubio walking the union picket lines, demanding stronger enforcement of workplace safety rules, and strong fiscal stimulus to counter unemployment. Oh, wait, Senator Rubio has been on the other side of all these issues. He has opposed strengthening workers’ rights to organize, stronger enforcement of workplace safety rules, as well as stimulus measures to counter unemployment.

That’s okay, in New York Times-land he still gets to be a “longtime champion of the working class.” The context is Senator Rubio’s fight for making more of the child tax credit refundable. His threat to hold out on this issue earned a slightly more generous provision that will net a single mother earning $20,000 about $300 a year.

This would be equivalent to an increase in the minimum wage of 15 cents an hour for a full-time year-round worker. It is equal to roughly 0.15 percent of the gains for the richest 0.1 percent of taxpayers. It’s great that we have The New York Times to tell us that Rubio is a champion of the working class, most of us would probably never realize it based on his actions.

Everyone remembers Marco Rubio walking the union picket lines, demanding stronger enforcement of workplace safety rules, and strong fiscal stimulus to counter unemployment. Oh, wait, Senator Rubio has been on the other side of all these issues. He has opposed strengthening workers’ rights to organize, stronger enforcement of workplace safety rules, as well as stimulus measures to counter unemployment.

That’s okay, in New York Times-land he still gets to be a “longtime champion of the working class.” The context is Senator Rubio’s fight for making more of the child tax credit refundable. His threat to hold out on this issue earned a slightly more generous provision that will net a single mother earning $20,000 about $300 a year.

This would be equivalent to an increase in the minimum wage of 15 cents an hour for a full-time year-round worker. It is equal to roughly 0.15 percent of the gains for the richest 0.1 percent of taxpayers. It’s great that we have The New York Times to tell us that Rubio is a champion of the working class, most of us would probably never realize it based on his actions.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT seems confused on how the new lower limit on mortgage interest deduction in the Republican tax bill would work. It told readers:

“The bill does retain significant subsidies, allowing home buyers to deduct interest on mortgages as high as $750,000.”

In fact, the bill allows homeowners to deduct interest on $750,000 of principal, regardless of the size of the mortgage. While the phrasing in the NYT piece might have led someone to believe that they could not deduct any interest on an $800,000 mortgage, in fact, they would be able to deduct almost all of their interest.

If a homeowner was paying 4.0 percent interest on an $800,000 mortgage, they would be able to deduct the interest on $750,000, or $30,000, from their taxable income. They would only lose out on the opportunity to deduct the $2,000 in interest on the $50,000 in principal above $750,000. Furthermore, after four or five years, when they had paid some of the principal, this homeowner would again be able to deduct the full amount of interest paid on their mortgage.

This distinction is important since the reduction in the cap on mortgage principal eligible for the interest deduction (from $1,000,000 to $750,000) is likely to have a very limited impact on the housing market. The doubling of the standard deduction and the cap on deductions for state and local income and property taxes are likely to be far more important.

Note: Typo corrected, thanks Raleedy.

The NYT seems confused on how the new lower limit on mortgage interest deduction in the Republican tax bill would work. It told readers:

“The bill does retain significant subsidies, allowing home buyers to deduct interest on mortgages as high as $750,000.”

In fact, the bill allows homeowners to deduct interest on $750,000 of principal, regardless of the size of the mortgage. While the phrasing in the NYT piece might have led someone to believe that they could not deduct any interest on an $800,000 mortgage, in fact, they would be able to deduct almost all of their interest.

If a homeowner was paying 4.0 percent interest on an $800,000 mortgage, they would be able to deduct the interest on $750,000, or $30,000, from their taxable income. They would only lose out on the opportunity to deduct the $2,000 in interest on the $50,000 in principal above $750,000. Furthermore, after four or five years, when they had paid some of the principal, this homeowner would again be able to deduct the full amount of interest paid on their mortgage.

This distinction is important since the reduction in the cap on mortgage principal eligible for the interest deduction (from $1,000,000 to $750,000) is likely to have a very limited impact on the housing market. The doubling of the standard deduction and the cap on deductions for state and local income and property taxes are likely to be far more important.

Note: Typo corrected, thanks Raleedy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Ryan Avent had a nice piece in the NYT this morning pushing the argument that Jared Bernstein, Josh Bivens, and I (among others) have been making for years, that higher wages can be a force driving more rapid productivity growth. The basic point is straightforward, when labor is expensive, employers have more incentive to find ways to use less of it. In this story, anything we can do to push up wages, like promoting unionization or raising minimum wages, is likely to lead to higher productivity.

The one important point that Ryan misses in this piece is that we may already be seeing a turning point. The tightening of the labor market over the last two years has led to upward pressure on wages, especially for those at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution. As Jared and I noted:

“The real weekly earnings for full-time, low-wage workers are up by more than 3 percent over the past two years. Real weekly earnings for the median African American worker have risen by more than 5 percent over the past two years, while the increase for Hispanics has been more than 4 percent.”

This rise in wages is the result of the fact that the Fed allowed the unemployment rate to keep falling to its current 4.1 percent rate rather than hiking interest rates enough to keep it near the 5.0 percent level that most economists considered the best we could do without triggering spiraling inflation.

It also looks as though higher wages may be producing the productivity dividend that we predicted. Productivity grew at a 3.0 percent annual rate in the third quarter, after growing 1.5 percent in the second quarter. With the latest projections showing GDP growth in the fourth quarter at 3.3 percent, productivity growth is likely to come in over 2.0 percent in the fourth quarter. This follows five years in which productivity growth averaged less than 0.7 percent annually.

Productivity data are notoriously erratic, so it is too early to declare the trend of weak growth over, but these are promising signs. And, there is no doubt that workers at the middle and bottom have seen decent wage growth over the last two years. These are important points to add to Ryan’s piece.

Ryan Avent had a nice piece in the NYT this morning pushing the argument that Jared Bernstein, Josh Bivens, and I (among others) have been making for years, that higher wages can be a force driving more rapid productivity growth. The basic point is straightforward, when labor is expensive, employers have more incentive to find ways to use less of it. In this story, anything we can do to push up wages, like promoting unionization or raising minimum wages, is likely to lead to higher productivity.

The one important point that Ryan misses in this piece is that we may already be seeing a turning point. The tightening of the labor market over the last two years has led to upward pressure on wages, especially for those at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution. As Jared and I noted:

“The real weekly earnings for full-time, low-wage workers are up by more than 3 percent over the past two years. Real weekly earnings for the median African American worker have risen by more than 5 percent over the past two years, while the increase for Hispanics has been more than 4 percent.”

This rise in wages is the result of the fact that the Fed allowed the unemployment rate to keep falling to its current 4.1 percent rate rather than hiking interest rates enough to keep it near the 5.0 percent level that most economists considered the best we could do without triggering spiraling inflation.

It also looks as though higher wages may be producing the productivity dividend that we predicted. Productivity grew at a 3.0 percent annual rate in the third quarter, after growing 1.5 percent in the second quarter. With the latest projections showing GDP growth in the fourth quarter at 3.3 percent, productivity growth is likely to come in over 2.0 percent in the fourth quarter. This follows five years in which productivity growth averaged less than 0.7 percent annually.

Productivity data are notoriously erratic, so it is too early to declare the trend of weak growth over, but these are promising signs. And, there is no doubt that workers at the middle and bottom have seen decent wage growth over the last two years. These are important points to add to Ryan’s piece.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I see that I got cited at the top of a NYT column this week. Desmond Lachman, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute (who I know and respect) had a column warning about the rise of bubbles around the world and the risk of their collapse. The first sentence tells us, “no one seemed to have anticipated the world’s worst financial crisis in the postwar period.” Yeah, well I realize I wasn’t very successful in getting my warnings across, but I sure did try.

Anyhow, I would say that Lachman is about half-right on the current situation. Many economies do seem to be seeing new bubbles. The housing markets in Canada, Australia, and the UK seem especially out of line. The bursting of bubbles in these markets is likely to be bad news for these countries; however, I don’t see comparable bubbles in the U.S. and most other major markets. If the more clearly identifiable bubbles burst, it does not look like 2008 all over again and a worldwide recession. (China looks bubbly too, but they have managed to go four decades without a recession, so I wouldn’t bet against them at this point.)

I see that I got cited at the top of a NYT column this week. Desmond Lachman, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute (who I know and respect) had a column warning about the rise of bubbles around the world and the risk of their collapse. The first sentence tells us, “no one seemed to have anticipated the world’s worst financial crisis in the postwar period.” Yeah, well I realize I wasn’t very successful in getting my warnings across, but I sure did try.

Anyhow, I would say that Lachman is about half-right on the current situation. Many economies do seem to be seeing new bubbles. The housing markets in Canada, Australia, and the UK seem especially out of line. The bursting of bubbles in these markets is likely to be bad news for these countries; however, I don’t see comparable bubbles in the U.S. and most other major markets. If the more clearly identifiable bubbles burst, it does not look like 2008 all over again and a worldwide recession. (China looks bubbly too, but they have managed to go four decades without a recession, so I wouldn’t bet against them at this point.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión