Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The centerpiece of the Republican tax cut was a big reduction in the corporate tax rate, lowering it from 35 percent to 21 percent. While critics argued this was just a handout to shareholders, who are overwhelmingly wealthy, the counter was the tax cut would lead to a surge in growth, which would benefit everyone.

The logic is that a lower tax rate provides more incentive to invest. With new investment in plant, equipment, and intellectual products, productivity will rise. Higher productivity will mean higher wages, which is good news for the bulk of the population that works for a living.

We got the first test of the jump in investment story today when the Commerce Department released data on capital goods orders for December. It is not good for the Republican position. New orders actually fell for the month, dropping by a modest 0.1 percent from the November level. Excluding aircraft orders, which are highly volatile, orders fell 0.3 percent.

These are not huge declines and this series is always erratic, so no one should make a big deal about the reported fall in December. But it certainly is hard to make the case here for some huge tax-induced jump.

If folks think it’s too early to make any assessment, let’s take the Republican argument at face value. They claim that the tax rate makes a huge difference in the investment decisions of firms. While the bill was just signed into law at the end of last month, it was pretty much a sure deal by the 20th. Furthermore, the basic outline was on the table at the start of September.

If the tax rate is really a big deal for investment decisions, then corporate America should have been putting together its list of likely projects as soon as a big tax cut became a clear possibility back in September. By December, forward-looking firms should have been ready to jump as soon as they knew the tax cut would be a reality.

This means that we should have seen at least some of these orders being registered before the end of the year. The fact that there is zero evidence of any uptick suggests that investment decisions are not as sensitive to tax rates as claimed.

It is, of course, early — maybe the January data will tell a different story. But so far, it doesn’t look the Republicans have much of a case. The tax cuts definitely made the rich richer, at this point we don’t have much evidence they will help anyone else.

The centerpiece of the Republican tax cut was a big reduction in the corporate tax rate, lowering it from 35 percent to 21 percent. While critics argued this was just a handout to shareholders, who are overwhelmingly wealthy, the counter was the tax cut would lead to a surge in growth, which would benefit everyone.

The logic is that a lower tax rate provides more incentive to invest. With new investment in plant, equipment, and intellectual products, productivity will rise. Higher productivity will mean higher wages, which is good news for the bulk of the population that works for a living.

We got the first test of the jump in investment story today when the Commerce Department released data on capital goods orders for December. It is not good for the Republican position. New orders actually fell for the month, dropping by a modest 0.1 percent from the November level. Excluding aircraft orders, which are highly volatile, orders fell 0.3 percent.

These are not huge declines and this series is always erratic, so no one should make a big deal about the reported fall in December. But it certainly is hard to make the case here for some huge tax-induced jump.

If folks think it’s too early to make any assessment, let’s take the Republican argument at face value. They claim that the tax rate makes a huge difference in the investment decisions of firms. While the bill was just signed into law at the end of last month, it was pretty much a sure deal by the 20th. Furthermore, the basic outline was on the table at the start of September.

If the tax rate is really a big deal for investment decisions, then corporate America should have been putting together its list of likely projects as soon as a big tax cut became a clear possibility back in September. By December, forward-looking firms should have been ready to jump as soon as they knew the tax cut would be a reality.

This means that we should have seen at least some of these orders being registered before the end of the year. The fact that there is zero evidence of any uptick suggests that investment decisions are not as sensitive to tax rates as claimed.

It is, of course, early — maybe the January data will tell a different story. But so far, it doesn’t look the Republicans have much of a case. The tax cuts definitely made the rich richer, at this point we don’t have much evidence they will help anyone else.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Morning Edition had a lengthy segment telling us that most workers are not worried about automation, even though we hear so much about it. Insofar as this is accurate, these workers are in agreement with the bulk of the economics profession.

Productivity growth (the rate at which technology is displacing workers) had slowed to roughly 1.0 percent annually in the years since 2005. This compares to a 3.0 percent growth rate in the decade from 1995 to 2005 and the long Golden Age from 1947 to 1973. Most economists expect the rate of productivity growth to remain near 1.0 percent as opposed to returning back to something close to its 3.0 percent rate in more prosperous times.

This difference is actually central to the disputes between the Trump administration and Democrats over the tax cuts. The Trump administration argued that the economy could grow at 3.0 percent annually, which would imply productivity growth somewhat over 2.0 percent. Most Democrats derided this view.

If we see a more rapid pace of automation then a 3.0 percent growth rate should be possible. If we actually got back to a 3.0 percent rate of productivity growth, then we could see GDP growth of close to 4.0 percent.

It is also worth noting that the high productivity growth in the period from 1947 to 1973 was associated with low unemployment and rapid wage growth. If another productivity upturn instead leads to high unemployment and weak wage growth it will be the result of deliberate policy to shift the benefits of productivity growth to those at the top end of the income distribution (e.g. government-granted patent and copyright monopolies, high interest rates by the Fed, and trade policy that protects doctors and other highly paid professionals from competition — all discussed in Rigged [it’s free]). It will not be the fault of the robots.

Morning Edition had a lengthy segment telling us that most workers are not worried about automation, even though we hear so much about it. Insofar as this is accurate, these workers are in agreement with the bulk of the economics profession.

Productivity growth (the rate at which technology is displacing workers) had slowed to roughly 1.0 percent annually in the years since 2005. This compares to a 3.0 percent growth rate in the decade from 1995 to 2005 and the long Golden Age from 1947 to 1973. Most economists expect the rate of productivity growth to remain near 1.0 percent as opposed to returning back to something close to its 3.0 percent rate in more prosperous times.

This difference is actually central to the disputes between the Trump administration and Democrats over the tax cuts. The Trump administration argued that the economy could grow at 3.0 percent annually, which would imply productivity growth somewhat over 2.0 percent. Most Democrats derided this view.

If we see a more rapid pace of automation then a 3.0 percent growth rate should be possible. If we actually got back to a 3.0 percent rate of productivity growth, then we could see GDP growth of close to 4.0 percent.

It is also worth noting that the high productivity growth in the period from 1947 to 1973 was associated with low unemployment and rapid wage growth. If another productivity upturn instead leads to high unemployment and weak wage growth it will be the result of deliberate policy to shift the benefits of productivity growth to those at the top end of the income distribution (e.g. government-granted patent and copyright monopolies, high interest rates by the Fed, and trade policy that protects doctors and other highly paid professionals from competition — all discussed in Rigged [it’s free]). It will not be the fault of the robots.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The level of ignorance among people who report on economic issues can really be astounding sometimes. Steven Mnuchin made a statement about trade that is almost definitionally true. He said a weaker dollar would improve the trade balance.

This is associated with the idea that a low price increases demand. When the US dollar falls, our exports are cheaper to people living in other countries. Fans of economics believe this will cause them to buy more US exports.

On the other side, imports are more expensive for people in the United States. This will mean that we will buy fewer imports and instead purchase more domestically produced items.

Somehow, the fact that Mnuchin accepts this simple economics is deemed major economic news. Of course, it does follow from this that a lower valued dollar would reduce the trade deficit. Mnuchin did not go so far as to argue for a lower valued dollar, unlike some prior Treasury Secretaries, but if the Trump administration actually cared about the trade deficit, this would be the logical way to go.

The level of ignorance among people who report on economic issues can really be astounding sometimes. Steven Mnuchin made a statement about trade that is almost definitionally true. He said a weaker dollar would improve the trade balance.

This is associated with the idea that a low price increases demand. When the US dollar falls, our exports are cheaper to people living in other countries. Fans of economics believe this will cause them to buy more US exports.

On the other side, imports are more expensive for people in the United States. This will mean that we will buy fewer imports and instead purchase more domestically produced items.

Somehow, the fact that Mnuchin accepts this simple economics is deemed major economic news. Of course, it does follow from this that a lower valued dollar would reduce the trade deficit. Mnuchin did not go so far as to argue for a lower valued dollar, unlike some prior Treasury Secretaries, but if the Trump administration actually cared about the trade deficit, this would be the logical way to go.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Actually, I really have no idea how hard Marvin Goodfriend works, but he did get everything wrong. Paul Krugman has a nice piece on Goodfriend, who is Trump’s nominee to be a governor of the Federal Reserve Board.

In this position, Goodfriend will have a major role in setting the country’s monetary policy. Goodfriend had been a persistent critic of the Fed’s efforts to boost the economy, expressing serious concerns about runaway inflation in the early days following the crash. He also thought it was pointless for the Fed to try to get the unemployment rate much below 8.0 percent.

But, America’s a great country. Driving a school bus into oncoming traffic shouldn’t ruin one’s career as a bus driver and not having a clue on monetary policy shouldn’t keep you from being put in the driver’s seat at the Fed.

Actually, I really have no idea how hard Marvin Goodfriend works, but he did get everything wrong. Paul Krugman has a nice piece on Goodfriend, who is Trump’s nominee to be a governor of the Federal Reserve Board.

In this position, Goodfriend will have a major role in setting the country’s monetary policy. Goodfriend had been a persistent critic of the Fed’s efforts to boost the economy, expressing serious concerns about runaway inflation in the early days following the crash. He also thought it was pointless for the Fed to try to get the unemployment rate much below 8.0 percent.

But, America’s a great country. Driving a school bus into oncoming traffic shouldn’t ruin one’s career as a bus driver and not having a clue on monetary policy shouldn’t keep you from being put in the driver’s seat at the Fed.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That seems like a reasonable question to ask. After all, we spend far more on prescription drugs, probably more than $470 billion or 2.4 percent of GDP this year, than we do on washing machines. And the protectionist barriers are far larger with drugs than with washing machines. Rather than adding 20 percent or 50 percent to the price of a washing machine, government-granted patent monopolies typically raise the price by around 1000 percent and sometimes more than 10,000 percent. And people don’t die due to lack of access to washing machines. And just as tariffs lead to economic waste and corruption, so do patent monopolies, except on a hugely greater scale.

It is probably worth noting that the people who benefit from protectionist measures on prescription drugs are overwhelmingly higher income and well-educated. The people who are ostensibly supposed to benefit from Trump’s tariffs are manufacturing workers, most of whom do not have college degrees.

That seems like a reasonable question to ask. After all, we spend far more on prescription drugs, probably more than $470 billion or 2.4 percent of GDP this year, than we do on washing machines. And the protectionist barriers are far larger with drugs than with washing machines. Rather than adding 20 percent or 50 percent to the price of a washing machine, government-granted patent monopolies typically raise the price by around 1000 percent and sometimes more than 10,000 percent. And people don’t die due to lack of access to washing machines. And just as tariffs lead to economic waste and corruption, so do patent monopolies, except on a hugely greater scale.

It is probably worth noting that the people who benefit from protectionist measures on prescription drugs are overwhelmingly higher income and well-educated. The people who are ostensibly supposed to benefit from Trump’s tariffs are manufacturing workers, most of whom do not have college degrees.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It didn’t actually directly say this, but that is certainly a likely outcome of one of the scenarios it describes in its description of some of the possible effects of ending NAFTA. After describing the ways in which the US and Canadian pork industries have become integrated and the possible impact of the end of NAFTA on this integration it tells readers:

“But this agricultural supply chain would be disrupted in other ways. American pork would face a tariff of 20 percent when moving into Mexico, which generally has higher tariffs. That would hurt American farmers.”

If Mexico did, in fact, impose a tariff on imports of American pork it would lower the price of pork in the United States. (That’s what it means to hurt American farmers.) Lower pork prices are of course bad news for those in the industry (and those who care about animal rights) but are good news for the vast majority of people in the United States who are not employed in the industry.

The point here is that the effort to imply that repealing NAFTA would be an economic disaster is largely overblown. Most of the likely impacts would be small and in most cases, there would be gains offsetting the losses, even if the latter might be larger than the former.

Also, the repeal of NAFTA does not mean that all three countries would adopt the highest possible tariffs allowed under the WTO. It’s not clear that Mexico’s government would think that it would improve its popularity if it made people in Mexico pay 20 percent more for pork due to a tariff. Presumably, US pork would eventually be replaced by pork from other countries, but the net effect will still almost certainly be higher pork prices for Mexican consumers. That is both bad economics and in all probability bad politics.

NAFTA was originally sold to the public with a slew of completely dishonest arguments about how it would lead to a boom in exports to Mexico and be a massive source of job creation. This was not at all what economic theory predicted and of course, it is not what happened. It would be nice if the argument for retaining NAFTA was not based on the same sort of deceptions.

It didn’t actually directly say this, but that is certainly a likely outcome of one of the scenarios it describes in its description of some of the possible effects of ending NAFTA. After describing the ways in which the US and Canadian pork industries have become integrated and the possible impact of the end of NAFTA on this integration it tells readers:

“But this agricultural supply chain would be disrupted in other ways. American pork would face a tariff of 20 percent when moving into Mexico, which generally has higher tariffs. That would hurt American farmers.”

If Mexico did, in fact, impose a tariff on imports of American pork it would lower the price of pork in the United States. (That’s what it means to hurt American farmers.) Lower pork prices are of course bad news for those in the industry (and those who care about animal rights) but are good news for the vast majority of people in the United States who are not employed in the industry.

The point here is that the effort to imply that repealing NAFTA would be an economic disaster is largely overblown. Most of the likely impacts would be small and in most cases, there would be gains offsetting the losses, even if the latter might be larger than the former.

Also, the repeal of NAFTA does not mean that all three countries would adopt the highest possible tariffs allowed under the WTO. It’s not clear that Mexico’s government would think that it would improve its popularity if it made people in Mexico pay 20 percent more for pork due to a tariff. Presumably, US pork would eventually be replaced by pork from other countries, but the net effect will still almost certainly be higher pork prices for Mexican consumers. That is both bad economics and in all probability bad politics.

NAFTA was originally sold to the public with a slew of completely dishonest arguments about how it would lead to a boom in exports to Mexico and be a massive source of job creation. This was not at all what economic theory predicted and of course, it is not what happened. It would be nice if the argument for retaining NAFTA was not based on the same sort of deceptions.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The 750 is a rough guess, but the NYT touted Macron’s commitment to “invest more than €15 million” in retraining programs. If we assume that a program cost 20,000 euros per worker (about $24,000), then 15 million euros should be enough to retrain somewhere around 750 workers. Since France’s labor force is almost 30 million, it may not be surprising that the French unions are not overly impressed with this commitment.

The piece presents France’s economy as lacking dynamism. This is not consistent with most data comparing France to other countries. According to the Conference Board, France’s GDP per hour of work was near the top in Europe in 2012 (the last year for which this series is available), slightly above Germany.

The piece notes that France’s unemployment rate has been “persistently stuck at more than 9 percent for nearly a decade.” However, its employment rate for prime-age (ages 25 to 54) workers is 80.2 percent, 1.7 percentage points higher than in the United States.

It also includes a reference to France’s rough unemployment rate “of more than 25 percent.” This is misleading since, unlike in the United States, most French young people are not in the labor force. Since college is nearly free and students get stipends to cover their cost of living, most colleges students don’t work. The percent of the youth population in France that is unemployed is close to 9.0 percent, not much higher than in the United States.

The 750 is a rough guess, but the NYT touted Macron’s commitment to “invest more than €15 million” in retraining programs. If we assume that a program cost 20,000 euros per worker (about $24,000), then 15 million euros should be enough to retrain somewhere around 750 workers. Since France’s labor force is almost 30 million, it may not be surprising that the French unions are not overly impressed with this commitment.

The piece presents France’s economy as lacking dynamism. This is not consistent with most data comparing France to other countries. According to the Conference Board, France’s GDP per hour of work was near the top in Europe in 2012 (the last year for which this series is available), slightly above Germany.

The piece notes that France’s unemployment rate has been “persistently stuck at more than 9 percent for nearly a decade.” However, its employment rate for prime-age (ages 25 to 54) workers is 80.2 percent, 1.7 percentage points higher than in the United States.

It also includes a reference to France’s rough unemployment rate “of more than 25 percent.” This is misleading since, unlike in the United States, most French young people are not in the labor force. Since college is nearly free and students get stipends to cover their cost of living, most colleges students don’t work. The percent of the youth population in France that is unemployed is close to 9.0 percent, not much higher than in the United States.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

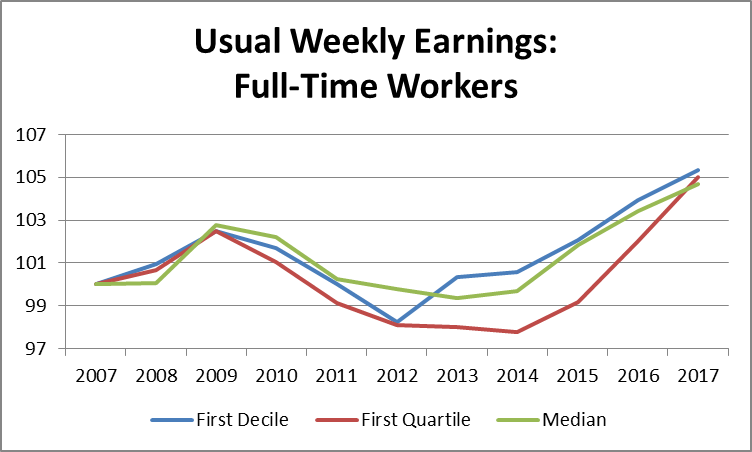

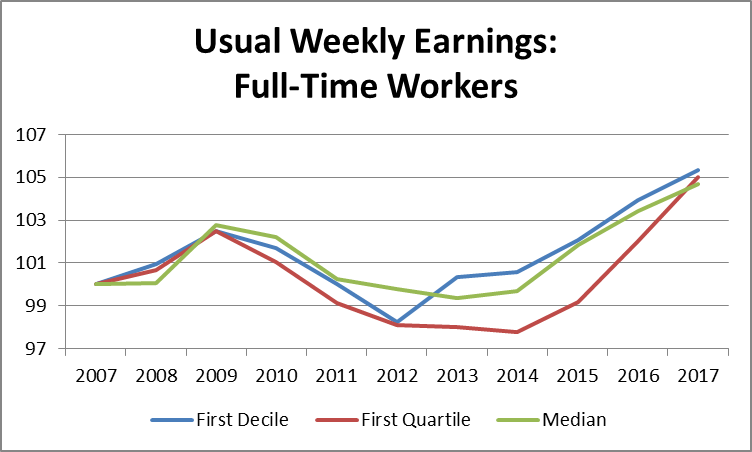

The Bureau of Labor Statistics released its eagerly awaited data on usual weekly earnings for the 4th quarter last week. The data for the 4th quarter were actually not very good, but the quarterly data are erratic. If we look at the full year data, we get a pretty good story. Real median weekly earnings were up 1.2 percent. Earnings for workers at the cutoff for the first quartile (earning more than 25 percent of workers and less than 75 percent) were up 2.9 percent. For workers at the cutoff for the first decile (earning more than 10 percent of workers and less than 90 percent), earnings were up 1.4 percent.

This means we have seen three years of pretty decent wage growth for those at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution. Here’s the picture since the Great Recession began in 2007.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In the last three years, earnings for the median worker have risen by 5.3 percent, for workers at the first quartile cutoff 7.1 percent, and by 5.0 percent at the first decile cutoff. This is pretty good evidence of the effect that a tight labor market has on the earnings of workers at the middle and bottom of the pay ladder. Even low-paying employers are finding that they have to raise wages to get and keep workers. (Note that this is all before the impact of the Trump tax cuts.)

This shows the importance of keeping the Fed from raising interest rates aggressively. There were many economists, including some at the Fed, who argued that the Fed should have raised interest rates to keep the unemployment rate from dipping much below 5.5 percent or 5.0 percent. With an unemployment rate now at 4.1 percent, not only do millions more workers have jobs, but tens of millions have higher pay because they have more bargaining power in the labor market.

One final point: while the last three years do look like good news for the bottom half of the labor market, we shouldn’t spend too much time celebrating. We’re still looking at a decade in which real wage growth has averaged just 0.5 percent annually. And this follows three decades of wage stagnation for the bottom half of the labor market. That is not a happy story, even if things are moving in the right direction now.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics released its eagerly awaited data on usual weekly earnings for the 4th quarter last week. The data for the 4th quarter were actually not very good, but the quarterly data are erratic. If we look at the full year data, we get a pretty good story. Real median weekly earnings were up 1.2 percent. Earnings for workers at the cutoff for the first quartile (earning more than 25 percent of workers and less than 75 percent) were up 2.9 percent. For workers at the cutoff for the first decile (earning more than 10 percent of workers and less than 90 percent), earnings were up 1.4 percent.

This means we have seen three years of pretty decent wage growth for those at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution. Here’s the picture since the Great Recession began in 2007.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In the last three years, earnings for the median worker have risen by 5.3 percent, for workers at the first quartile cutoff 7.1 percent, and by 5.0 percent at the first decile cutoff. This is pretty good evidence of the effect that a tight labor market has on the earnings of workers at the middle and bottom of the pay ladder. Even low-paying employers are finding that they have to raise wages to get and keep workers. (Note that this is all before the impact of the Trump tax cuts.)

This shows the importance of keeping the Fed from raising interest rates aggressively. There were many economists, including some at the Fed, who argued that the Fed should have raised interest rates to keep the unemployment rate from dipping much below 5.5 percent or 5.0 percent. With an unemployment rate now at 4.1 percent, not only do millions more workers have jobs, but tens of millions have higher pay because they have more bargaining power in the labor market.

One final point: while the last three years do look like good news for the bottom half of the labor market, we shouldn’t spend too much time celebrating. We’re still looking at a decade in which real wage growth has averaged just 0.5 percent annually. And this follows three decades of wage stagnation for the bottom half of the labor market. That is not a happy story, even if things are moving in the right direction now.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión