The level of ignorance among people who report on economic issues can really be astounding sometimes. Steven Mnuchin made a statement about trade that is almost definitionally true. He said a weaker dollar would improve the trade balance.

This is associated with the idea that a low price increases demand. When the US dollar falls, our exports are cheaper to people living in other countries. Fans of economics believe this will cause them to buy more US exports.

On the other side, imports are more expensive for people in the United States. This will mean that we will buy fewer imports and instead purchase more domestically produced items.

Somehow, the fact that Mnuchin accepts this simple economics is deemed major economic news. Of course, it does follow from this that a lower valued dollar would reduce the trade deficit. Mnuchin did not go so far as to argue for a lower valued dollar, unlike some prior Treasury Secretaries, but if the Trump administration actually cared about the trade deficit, this would be the logical way to go.

The level of ignorance among people who report on economic issues can really be astounding sometimes. Steven Mnuchin made a statement about trade that is almost definitionally true. He said a weaker dollar would improve the trade balance.

This is associated with the idea that a low price increases demand. When the US dollar falls, our exports are cheaper to people living in other countries. Fans of economics believe this will cause them to buy more US exports.

On the other side, imports are more expensive for people in the United States. This will mean that we will buy fewer imports and instead purchase more domestically produced items.

Somehow, the fact that Mnuchin accepts this simple economics is deemed major economic news. Of course, it does follow from this that a lower valued dollar would reduce the trade deficit. Mnuchin did not go so far as to argue for a lower valued dollar, unlike some prior Treasury Secretaries, but if the Trump administration actually cared about the trade deficit, this would be the logical way to go.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Actually, I really have no idea how hard Marvin Goodfriend works, but he did get everything wrong. Paul Krugman has a nice piece on Goodfriend, who is Trump’s nominee to be a governor of the Federal Reserve Board.

In this position, Goodfriend will have a major role in setting the country’s monetary policy. Goodfriend had been a persistent critic of the Fed’s efforts to boost the economy, expressing serious concerns about runaway inflation in the early days following the crash. He also thought it was pointless for the Fed to try to get the unemployment rate much below 8.0 percent.

But, America’s a great country. Driving a school bus into oncoming traffic shouldn’t ruin one’s career as a bus driver and not having a clue on monetary policy shouldn’t keep you from being put in the driver’s seat at the Fed.

Actually, I really have no idea how hard Marvin Goodfriend works, but he did get everything wrong. Paul Krugman has a nice piece on Goodfriend, who is Trump’s nominee to be a governor of the Federal Reserve Board.

In this position, Goodfriend will have a major role in setting the country’s monetary policy. Goodfriend had been a persistent critic of the Fed’s efforts to boost the economy, expressing serious concerns about runaway inflation in the early days following the crash. He also thought it was pointless for the Fed to try to get the unemployment rate much below 8.0 percent.

But, America’s a great country. Driving a school bus into oncoming traffic shouldn’t ruin one’s career as a bus driver and not having a clue on monetary policy shouldn’t keep you from being put in the driver’s seat at the Fed.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That seems like a reasonable question to ask. After all, we spend far more on prescription drugs, probably more than $470 billion or 2.4 percent of GDP this year, than we do on washing machines. And the protectionist barriers are far larger with drugs than with washing machines. Rather than adding 20 percent or 50 percent to the price of a washing machine, government-granted patent monopolies typically raise the price by around 1000 percent and sometimes more than 10,000 percent. And people don’t die due to lack of access to washing machines. And just as tariffs lead to economic waste and corruption, so do patent monopolies, except on a hugely greater scale.

It is probably worth noting that the people who benefit from protectionist measures on prescription drugs are overwhelmingly higher income and well-educated. The people who are ostensibly supposed to benefit from Trump’s tariffs are manufacturing workers, most of whom do not have college degrees.

That seems like a reasonable question to ask. After all, we spend far more on prescription drugs, probably more than $470 billion or 2.4 percent of GDP this year, than we do on washing machines. And the protectionist barriers are far larger with drugs than with washing machines. Rather than adding 20 percent or 50 percent to the price of a washing machine, government-granted patent monopolies typically raise the price by around 1000 percent and sometimes more than 10,000 percent. And people don’t die due to lack of access to washing machines. And just as tariffs lead to economic waste and corruption, so do patent monopolies, except on a hugely greater scale.

It is probably worth noting that the people who benefit from protectionist measures on prescription drugs are overwhelmingly higher income and well-educated. The people who are ostensibly supposed to benefit from Trump’s tariffs are manufacturing workers, most of whom do not have college degrees.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It didn’t actually directly say this, but that is certainly a likely outcome of one of the scenarios it describes in its description of some of the possible effects of ending NAFTA. After describing the ways in which the US and Canadian pork industries have become integrated and the possible impact of the end of NAFTA on this integration it tells readers:

“But this agricultural supply chain would be disrupted in other ways. American pork would face a tariff of 20 percent when moving into Mexico, which generally has higher tariffs. That would hurt American farmers.”

If Mexico did, in fact, impose a tariff on imports of American pork it would lower the price of pork in the United States. (That’s what it means to hurt American farmers.) Lower pork prices are of course bad news for those in the industry (and those who care about animal rights) but are good news for the vast majority of people in the United States who are not employed in the industry.

The point here is that the effort to imply that repealing NAFTA would be an economic disaster is largely overblown. Most of the likely impacts would be small and in most cases, there would be gains offsetting the losses, even if the latter might be larger than the former.

Also, the repeal of NAFTA does not mean that all three countries would adopt the highest possible tariffs allowed under the WTO. It’s not clear that Mexico’s government would think that it would improve its popularity if it made people in Mexico pay 20 percent more for pork due to a tariff. Presumably, US pork would eventually be replaced by pork from other countries, but the net effect will still almost certainly be higher pork prices for Mexican consumers. That is both bad economics and in all probability bad politics.

NAFTA was originally sold to the public with a slew of completely dishonest arguments about how it would lead to a boom in exports to Mexico and be a massive source of job creation. This was not at all what economic theory predicted and of course, it is not what happened. It would be nice if the argument for retaining NAFTA was not based on the same sort of deceptions.

It didn’t actually directly say this, but that is certainly a likely outcome of one of the scenarios it describes in its description of some of the possible effects of ending NAFTA. After describing the ways in which the US and Canadian pork industries have become integrated and the possible impact of the end of NAFTA on this integration it tells readers:

“But this agricultural supply chain would be disrupted in other ways. American pork would face a tariff of 20 percent when moving into Mexico, which generally has higher tariffs. That would hurt American farmers.”

If Mexico did, in fact, impose a tariff on imports of American pork it would lower the price of pork in the United States. (That’s what it means to hurt American farmers.) Lower pork prices are of course bad news for those in the industry (and those who care about animal rights) but are good news for the vast majority of people in the United States who are not employed in the industry.

The point here is that the effort to imply that repealing NAFTA would be an economic disaster is largely overblown. Most of the likely impacts would be small and in most cases, there would be gains offsetting the losses, even if the latter might be larger than the former.

Also, the repeal of NAFTA does not mean that all three countries would adopt the highest possible tariffs allowed under the WTO. It’s not clear that Mexico’s government would think that it would improve its popularity if it made people in Mexico pay 20 percent more for pork due to a tariff. Presumably, US pork would eventually be replaced by pork from other countries, but the net effect will still almost certainly be higher pork prices for Mexican consumers. That is both bad economics and in all probability bad politics.

NAFTA was originally sold to the public with a slew of completely dishonest arguments about how it would lead to a boom in exports to Mexico and be a massive source of job creation. This was not at all what economic theory predicted and of course, it is not what happened. It would be nice if the argument for retaining NAFTA was not based on the same sort of deceptions.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The 750 is a rough guess, but the NYT touted Macron’s commitment to “invest more than €15 million” in retraining programs. If we assume that a program cost 20,000 euros per worker (about $24,000), then 15 million euros should be enough to retrain somewhere around 750 workers. Since France’s labor force is almost 30 million, it may not be surprising that the French unions are not overly impressed with this commitment.

The piece presents France’s economy as lacking dynamism. This is not consistent with most data comparing France to other countries. According to the Conference Board, France’s GDP per hour of work was near the top in Europe in 2012 (the last year for which this series is available), slightly above Germany.

The piece notes that France’s unemployment rate has been “persistently stuck at more than 9 percent for nearly a decade.” However, its employment rate for prime-age (ages 25 to 54) workers is 80.2 percent, 1.7 percentage points higher than in the United States.

It also includes a reference to France’s rough unemployment rate “of more than 25 percent.” This is misleading since, unlike in the United States, most French young people are not in the labor force. Since college is nearly free and students get stipends to cover their cost of living, most colleges students don’t work. The percent of the youth population in France that is unemployed is close to 9.0 percent, not much higher than in the United States.

The 750 is a rough guess, but the NYT touted Macron’s commitment to “invest more than €15 million” in retraining programs. If we assume that a program cost 20,000 euros per worker (about $24,000), then 15 million euros should be enough to retrain somewhere around 750 workers. Since France’s labor force is almost 30 million, it may not be surprising that the French unions are not overly impressed with this commitment.

The piece presents France’s economy as lacking dynamism. This is not consistent with most data comparing France to other countries. According to the Conference Board, France’s GDP per hour of work was near the top in Europe in 2012 (the last year for which this series is available), slightly above Germany.

The piece notes that France’s unemployment rate has been “persistently stuck at more than 9 percent for nearly a decade.” However, its employment rate for prime-age (ages 25 to 54) workers is 80.2 percent, 1.7 percentage points higher than in the United States.

It also includes a reference to France’s rough unemployment rate “of more than 25 percent.” This is misleading since, unlike in the United States, most French young people are not in the labor force. Since college is nearly free and students get stipends to cover their cost of living, most colleges students don’t work. The percent of the youth population in France that is unemployed is close to 9.0 percent, not much higher than in the United States.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

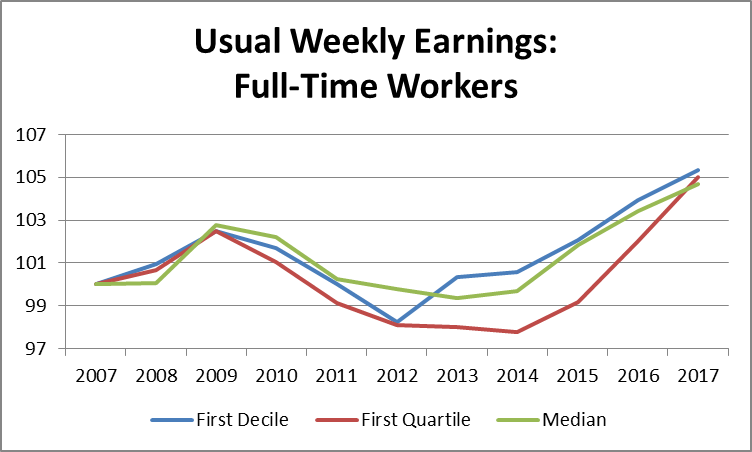

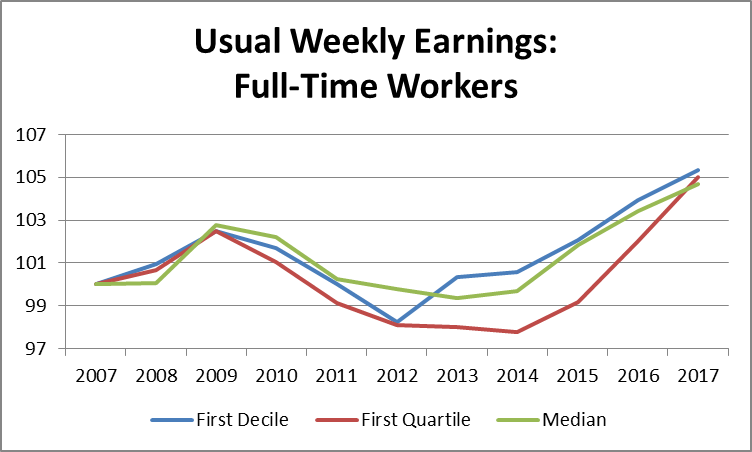

The Bureau of Labor Statistics released its eagerly awaited data on usual weekly earnings for the 4th quarter last week. The data for the 4th quarter were actually not very good, but the quarterly data are erratic. If we look at the full year data, we get a pretty good story. Real median weekly earnings were up 1.2 percent. Earnings for workers at the cutoff for the first quartile (earning more than 25 percent of workers and less than 75 percent) were up 2.9 percent. For workers at the cutoff for the first decile (earning more than 10 percent of workers and less than 90 percent), earnings were up 1.4 percent.

This means we have seen three years of pretty decent wage growth for those at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution. Here’s the picture since the Great Recession began in 2007.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In the last three years, earnings for the median worker have risen by 5.3 percent, for workers at the first quartile cutoff 7.1 percent, and by 5.0 percent at the first decile cutoff. This is pretty good evidence of the effect that a tight labor market has on the earnings of workers at the middle and bottom of the pay ladder. Even low-paying employers are finding that they have to raise wages to get and keep workers. (Note that this is all before the impact of the Trump tax cuts.)

This shows the importance of keeping the Fed from raising interest rates aggressively. There were many economists, including some at the Fed, who argued that the Fed should have raised interest rates to keep the unemployment rate from dipping much below 5.5 percent or 5.0 percent. With an unemployment rate now at 4.1 percent, not only do millions more workers have jobs, but tens of millions have higher pay because they have more bargaining power in the labor market.

One final point: while the last three years do look like good news for the bottom half of the labor market, we shouldn’t spend too much time celebrating. We’re still looking at a decade in which real wage growth has averaged just 0.5 percent annually. And this follows three decades of wage stagnation for the bottom half of the labor market. That is not a happy story, even if things are moving in the right direction now.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics released its eagerly awaited data on usual weekly earnings for the 4th quarter last week. The data for the 4th quarter were actually not very good, but the quarterly data are erratic. If we look at the full year data, we get a pretty good story. Real median weekly earnings were up 1.2 percent. Earnings for workers at the cutoff for the first quartile (earning more than 25 percent of workers and less than 75 percent) were up 2.9 percent. For workers at the cutoff for the first decile (earning more than 10 percent of workers and less than 90 percent), earnings were up 1.4 percent.

This means we have seen three years of pretty decent wage growth for those at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution. Here’s the picture since the Great Recession began in 2007.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In the last three years, earnings for the median worker have risen by 5.3 percent, for workers at the first quartile cutoff 7.1 percent, and by 5.0 percent at the first decile cutoff. This is pretty good evidence of the effect that a tight labor market has on the earnings of workers at the middle and bottom of the pay ladder. Even low-paying employers are finding that they have to raise wages to get and keep workers. (Note that this is all before the impact of the Trump tax cuts.)

This shows the importance of keeping the Fed from raising interest rates aggressively. There were many economists, including some at the Fed, who argued that the Fed should have raised interest rates to keep the unemployment rate from dipping much below 5.5 percent or 5.0 percent. With an unemployment rate now at 4.1 percent, not only do millions more workers have jobs, but tens of millions have higher pay because they have more bargaining power in the labor market.

One final point: while the last three years do look like good news for the bottom half of the labor market, we shouldn’t spend too much time celebrating. We’re still looking at a decade in which real wage growth has averaged just 0.5 percent annually. And this follows three decades of wage stagnation for the bottom half of the labor market. That is not a happy story, even if things are moving in the right direction now.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Actually, it’s not clear that the 200 jobs were due to Trump since the biggest factor appears to be higher world energy prices. Trump is not obviously responsible for rising oil and gas prices, but I suppose there is some way that his administration can take the credit/blame for people paying more for their gas and heat. Even with the new jobs, employment in the sector is still down by almost one-third from its average under President Obama.

In any case, the new coal mining jobs bring the total in Pennsylvania to 5000, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Total employment in Pennsylvania is 6,043,000 jobs, which means that the coal industry accounts for 0.08 percent of total employment in the state. Given its limited importance to the state’s economy, it is difficult to see why NPR would devote so much attention to the industry.

Actually, it’s not clear that the 200 jobs were due to Trump since the biggest factor appears to be higher world energy prices. Trump is not obviously responsible for rising oil and gas prices, but I suppose there is some way that his administration can take the credit/blame for people paying more for their gas and heat. Even with the new jobs, employment in the sector is still down by almost one-third from its average under President Obama.

In any case, the new coal mining jobs bring the total in Pennsylvania to 5000, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Total employment in Pennsylvania is 6,043,000 jobs, which means that the coal industry accounts for 0.08 percent of total employment in the state. Given its limited importance to the state’s economy, it is difficult to see why NPR would devote so much attention to the industry.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This is what bringing money back to the United States means. Under the old tax law, companies often attributed legal control of profits to foreign subsidiaries, so that they could defer paying taxes on this money. However, the money was often actually held in the United States since Apple could tell the subsidiary to keep the money wherever it wanted.

For this reason, the economic significance of bringing the money back to the United States is almost zero. The legal change of ownership is leading to the collection of taxes, but this is in lieu of the considerably larger tax liability that Apple faced under the old law.

It would have been helpful if these points were made more clearly in this NYT piece. It does usefully point out that we don’t know the extent to which the expansion plans announced by Apple would have occurred even without the tax cut.

Addendum

It is probably worth also mentioning that the $2,500 one time bonuses that Apple said it is giving its workers (paid in stock) is a bit less than 0.5 percent of the tax savings on their foreign earnings as calculated by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, which is cited in the article. This assumes that all 84,000 Apple workers get the bonus.

This is what bringing money back to the United States means. Under the old tax law, companies often attributed legal control of profits to foreign subsidiaries, so that they could defer paying taxes on this money. However, the money was often actually held in the United States since Apple could tell the subsidiary to keep the money wherever it wanted.

For this reason, the economic significance of bringing the money back to the United States is almost zero. The legal change of ownership is leading to the collection of taxes, but this is in lieu of the considerably larger tax liability that Apple faced under the old law.

It would have been helpful if these points were made more clearly in this NYT piece. It does usefully point out that we don’t know the extent to which the expansion plans announced by Apple would have occurred even without the tax cut.

Addendum

It is probably worth also mentioning that the $2,500 one time bonuses that Apple said it is giving its workers (paid in stock) is a bit less than 0.5 percent of the tax savings on their foreign earnings as calculated by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, which is cited in the article. This assumes that all 84,000 Apple workers get the bonus.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión