An NYT Magazine piece does a very nice job laying out the argument as to how platform monopolies like Google could be engaging in anti-competitive practices.

An NYT Magazine piece does a very nice job laying out the argument as to how platform monopolies like Google could be engaging in anti-competitive practices.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is amazing how frequently we hear people asserting that the massive inequality we are now seeing in the United States is the result of an unfettered market. I realize that this is a convenient view for those who are on the upside of things, but it also happens to be nonsense.

Today’s highlighted nonsense pusher is Amy Chua, who warns in an NYT column about the destructive path the United States is now on where a disaffected white population takes out its wrath on economic elites and racial minorities. The key part missing from the story is that disaffected masses really do have a legitimate gripe.

We didn’t have to make patent and copyright monopolies ever longer and stronger, allowing folks like Bill Gates to get incredibly rich. We could have made Amazon pay the same sales tax as their mom and pop competitors, which would mean Jeff Bezos would not be incredibly rich. We could subject Wall Street financial transactions to the same sort of sales taxes as people pay on shoes and clothes, hugely downsizing the high incomes earned in this sector. And, we could have rules of corporate governance that make it easier for shareholders to rein in CEO pay.

None of the rules we have in place that redistribute upward were given to us by the market. They were the result of deliberate economic policy. (Yes, this is the topic of my [free] book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.) It is understandable that the losers from this upward redistribution would be resentful and they likely are even more resentful when the beneficiaries of the rigging just pretend that it was just a natural outcome of the market.

It is amazing how frequently we hear people asserting that the massive inequality we are now seeing in the United States is the result of an unfettered market. I realize that this is a convenient view for those who are on the upside of things, but it also happens to be nonsense.

Today’s highlighted nonsense pusher is Amy Chua, who warns in an NYT column about the destructive path the United States is now on where a disaffected white population takes out its wrath on economic elites and racial minorities. The key part missing from the story is that disaffected masses really do have a legitimate gripe.

We didn’t have to make patent and copyright monopolies ever longer and stronger, allowing folks like Bill Gates to get incredibly rich. We could have made Amazon pay the same sales tax as their mom and pop competitors, which would mean Jeff Bezos would not be incredibly rich. We could subject Wall Street financial transactions to the same sort of sales taxes as people pay on shoes and clothes, hugely downsizing the high incomes earned in this sector. And, we could have rules of corporate governance that make it easier for shareholders to rein in CEO pay.

None of the rules we have in place that redistribute upward were given to us by the market. They were the result of deliberate economic policy. (Yes, this is the topic of my [free] book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.) It is understandable that the losers from this upward redistribution would be resentful and they likely are even more resentful when the beneficiaries of the rigging just pretend that it was just a natural outcome of the market.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In the last six months, Republicans gave up being a party that pretends to care about budget deficits as they happily pushed through large tax cuts (roughly 0.7 percent of GDP over the next decade) and big increases in spending (roughly 0.7 percent of GDP over the next two years). The deficit picture looks much worse today than it did a year ago.

While the few remaining deficit hawks at the Washington Post and the Peter Peterson–funded organizations are screaming, the question serious people should be asking is: why don’t the markets don’t share their concerns? In particular, the bond market, where the “bond vigilantes” live, should be going nuts with much larger deficits now being projected for as far as the eye can see.

It is true that rates have gone up. At just under 2.9 percent, the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds is almost half a percentage point higher than it was a year ago. But a 2.9 percent rate is still very low by any reasonable standard. After all, it was over 3.0 percent at the end of 2013 and it was over 5.0 percent in the late 1990s as the deficits were turning to surpluses.

The current 2.9 percent rate is also well below what the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) had projected just a couple of years ago when it expected deficits to stay on their prior no tax cut path. In January of 2016, CBO projected that the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds would be 3.7 percent by now. This means that even with the recent run-up, long-term interests are still 0.8 percentage points below what CBO had projected without any major increases in the budget deficit.

This might suggest that the concerns that deficits would send interest rates through the roof have little basis in reality. After all, long-term interest rates are driven by expectations, and unless investors in the bond market have hugely different expectations about the size of deficits than folks in Washington, they apparently don’t believe that the larger deficits we are now looking at are that big a deal.

In the last six months, Republicans gave up being a party that pretends to care about budget deficits as they happily pushed through large tax cuts (roughly 0.7 percent of GDP over the next decade) and big increases in spending (roughly 0.7 percent of GDP over the next two years). The deficit picture looks much worse today than it did a year ago.

While the few remaining deficit hawks at the Washington Post and the Peter Peterson–funded organizations are screaming, the question serious people should be asking is: why don’t the markets don’t share their concerns? In particular, the bond market, where the “bond vigilantes” live, should be going nuts with much larger deficits now being projected for as far as the eye can see.

It is true that rates have gone up. At just under 2.9 percent, the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds is almost half a percentage point higher than it was a year ago. But a 2.9 percent rate is still very low by any reasonable standard. After all, it was over 3.0 percent at the end of 2013 and it was over 5.0 percent in the late 1990s as the deficits were turning to surpluses.

The current 2.9 percent rate is also well below what the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) had projected just a couple of years ago when it expected deficits to stay on their prior no tax cut path. In January of 2016, CBO projected that the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds would be 3.7 percent by now. This means that even with the recent run-up, long-term interests are still 0.8 percentage points below what CBO had projected without any major increases in the budget deficit.

This might suggest that the concerns that deficits would send interest rates through the roof have little basis in reality. After all, long-term interest rates are driven by expectations, and unless investors in the bond market have hugely different expectations about the size of deficits than folks in Washington, they apparently don’t believe that the larger deficits we are now looking at are that big a deal.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This is an assertion in a major Post article on infrastructure, but it doesn’t fit with the evidence. Trump is actually only proposing to put up $200 billion (0.09 percent of GDP) over the next decade towards his infrastructure initiative.

The rest is supposed to come from state and local governments and private investors. As the piece notes, many are dubious whether anything like this amount will be forthcoming. Also, Trump is proposing large cuts to Amtrak and a wide range of other areas of infrastructure spending, so his proposed increase in spending is far less this $200 billion figure.

While the Post wants to assure readers that Trump really expects that his proposal might lead to an increase in infrastructure spending of $1.5 trillion (0.7 percent of GDP) over the next decade, let me suggest an alternative possibility. Trump made big promises about infrastructure spending during the campaign. It is likely that many of his supporters took these promises seriously.

However, Trump really doesn’t give a damn about infrastructure and the Republicans in Congress are not willing to increase the deficit, give back part of their tax cut, or reduce military spending to accommodate additional infrastructure spending. Therefore, Trump goes out and touts a plan that everyone knows doesn’t add up but still allows him to pretend to be meeting his commitment to his base.

I have no idea if my alternative scenario is accurate, but I would argue that it is at least as plausible as the Post’s claim that Trump or anyone else actually expects this plan to produce $1.5 trillion in additional infrastructure spending. Since neither the Post nor I know what is in the heads of Trump and his top aides, how about they just report the plan and what Trump’s people say about it, and not claim to know what anyone’s real “aims” are.

This is an assertion in a major Post article on infrastructure, but it doesn’t fit with the evidence. Trump is actually only proposing to put up $200 billion (0.09 percent of GDP) over the next decade towards his infrastructure initiative.

The rest is supposed to come from state and local governments and private investors. As the piece notes, many are dubious whether anything like this amount will be forthcoming. Also, Trump is proposing large cuts to Amtrak and a wide range of other areas of infrastructure spending, so his proposed increase in spending is far less this $200 billion figure.

While the Post wants to assure readers that Trump really expects that his proposal might lead to an increase in infrastructure spending of $1.5 trillion (0.7 percent of GDP) over the next decade, let me suggest an alternative possibility. Trump made big promises about infrastructure spending during the campaign. It is likely that many of his supporters took these promises seriously.

However, Trump really doesn’t give a damn about infrastructure and the Republicans in Congress are not willing to increase the deficit, give back part of their tax cut, or reduce military spending to accommodate additional infrastructure spending. Therefore, Trump goes out and touts a plan that everyone knows doesn’t add up but still allows him to pretend to be meeting his commitment to his base.

I have no idea if my alternative scenario is accurate, but I would argue that it is at least as plausible as the Post’s claim that Trump or anyone else actually expects this plan to produce $1.5 trillion in additional infrastructure spending. Since neither the Post nor I know what is in the heads of Trump and his top aides, how about they just report the plan and what Trump’s people say about it, and not claim to know what anyone’s real “aims” are.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It seems that bad guys (Russians and others) are using Facebook to spread all sorts of nonsense under false identities. Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s CEO and very rich person, tells us that he is very concerned about the problem but doesn’t know exactly what to do. Congress can help out Facebook and Zuckerberg.

Back in the late 1990s, when the Internet was rapidly becoming an important means of communication, the entertainment industry became concerned about people transferring copies of copyrighted music without permission. It got Congress to pass the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 (DMCA).

There are many aspects to the DMCA, but the key part is that it imposes harsh punitive damages for anyone who allows copyrighted material to be transferred through their site. If a copyright holder notifies the owner of the site that they have posted their material without authorization, the owner of the site must remove it within 48 hours or face steep penalties.

The site owner is liable for damages even if a third party posted the infringing material. This means that if someone were to post a copyrighted song in the comments section to this blog, CEPR would be liable if it was not removed after notification.

It is important to note that the damages are punitive, not just actual. Suppose someone posts a minor hit from thirty years ago that 20 people download from this site. Given the prices commanded for downloads of old music, the actual damages would be a few cents. Nonetheless, under the DMCA, CEPR could be liable for thousands of dollars in damages. This can be a great model for Facebook and other potential purveyors of fake news.

Here’s how it would work. Imagine that I get a posting on my Facebook feed from something that looks dubious. I send a note to Facebook indicating that I don’t think that this posting is from a real source. Facebook then has 48 hours to investigate and determine if the source is real. If it determines that it is not real it must notify every person who received the posting, either directly or through its sharing system, that the source was fake.

Just as is the case with the DMCA, Facebook could face stiff penalties, say $10,000 a shot, for failing to act within the 48-hour time frame. This would ensure that Facebook would have a powerful incentive to move quickly to prevent the spread of fake news and false stories.

My guess is that Facebook has the technical expertise to meet this requirement. But if it doesn’t, who gives a damn? This is a reasonable expectation of a system like Facebook and if Mark Zuckerberg and his crew lack the competence to meet it, then a better run competitor will take its place.

See, this is all fun and easy. It just requires a Congress that cares as much about protecting democracy as the copyrights of Disney and Time-Warner.

It seems that bad guys (Russians and others) are using Facebook to spread all sorts of nonsense under false identities. Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s CEO and very rich person, tells us that he is very concerned about the problem but doesn’t know exactly what to do. Congress can help out Facebook and Zuckerberg.

Back in the late 1990s, when the Internet was rapidly becoming an important means of communication, the entertainment industry became concerned about people transferring copies of copyrighted music without permission. It got Congress to pass the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 (DMCA).

There are many aspects to the DMCA, but the key part is that it imposes harsh punitive damages for anyone who allows copyrighted material to be transferred through their site. If a copyright holder notifies the owner of the site that they have posted their material without authorization, the owner of the site must remove it within 48 hours or face steep penalties.

The site owner is liable for damages even if a third party posted the infringing material. This means that if someone were to post a copyrighted song in the comments section to this blog, CEPR would be liable if it was not removed after notification.

It is important to note that the damages are punitive, not just actual. Suppose someone posts a minor hit from thirty years ago that 20 people download from this site. Given the prices commanded for downloads of old music, the actual damages would be a few cents. Nonetheless, under the DMCA, CEPR could be liable for thousands of dollars in damages. This can be a great model for Facebook and other potential purveyors of fake news.

Here’s how it would work. Imagine that I get a posting on my Facebook feed from something that looks dubious. I send a note to Facebook indicating that I don’t think that this posting is from a real source. Facebook then has 48 hours to investigate and determine if the source is real. If it determines that it is not real it must notify every person who received the posting, either directly or through its sharing system, that the source was fake.

Just as is the case with the DMCA, Facebook could face stiff penalties, say $10,000 a shot, for failing to act within the 48-hour time frame. This would ensure that Facebook would have a powerful incentive to move quickly to prevent the spread of fake news and false stories.

My guess is that Facebook has the technical expertise to meet this requirement. But if it doesn’t, who gives a damn? This is a reasonable expectation of a system like Facebook and if Mark Zuckerberg and his crew lack the competence to meet it, then a better run competitor will take its place.

See, this is all fun and easy. It just requires a Congress that cares as much about protecting democracy as the copyrights of Disney and Time-Warner.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

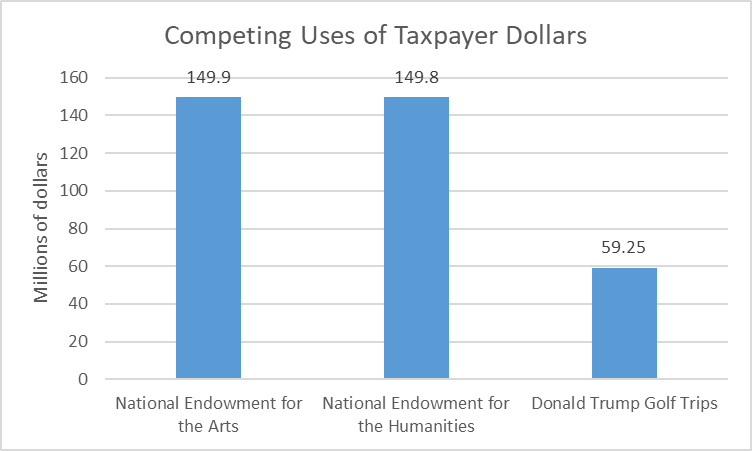

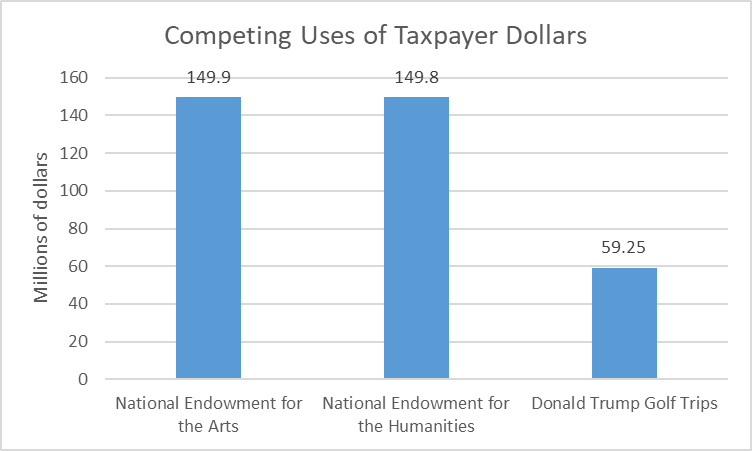

Donald Trump is proposing to eliminate the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, as noted in an NYT column today. Each agency received just under $150 million in the 2017 budget, an amount that is equal to just under 0.004 percent of total spending. Another way to think about the money the government spends promoting the arts and the humanities is comparing it to spending on Donald Trump’s golfing trips.

According to calculations from the Center for American Progress Action Fund, we were on a path to spend $59.25 million on Donald Trump’s golfing for each year he is in the White House. This means that by ending funding for either the Endowment for the Arts or the Endowment for the Humanities we can pay for two and a half years of Donald Trump’s golf trips. If both are shut down, it would cover the cost of five years of Donald Trump’s golf trips.

Source: See text.

Donald Trump is proposing to eliminate the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, as noted in an NYT column today. Each agency received just under $150 million in the 2017 budget, an amount that is equal to just under 0.004 percent of total spending. Another way to think about the money the government spends promoting the arts and the humanities is comparing it to spending on Donald Trump’s golfing trips.

According to calculations from the Center for American Progress Action Fund, we were on a path to spend $59.25 million on Donald Trump’s golfing for each year he is in the White House. This means that by ending funding for either the Endowment for the Arts or the Endowment for the Humanities we can pay for two and a half years of Donald Trump’s golf trips. If both are shut down, it would cover the cost of five years of Donald Trump’s golf trips.

Source: See text.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post reported on new health care spending projections from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) which show spending rising to almost 20 percent of GDP by 2026 compared to 17.9 percent in 2016. It is worth noting that these projections have consistently overstated cost growth. For example in 2005, CMS projected that health care costs would rise to 19.6 percent of GDP in 2016.

The piece also notes that prescription drugs are projected to be the most rapidly growing component of health care costs. It is worth mentioning that prescription drugs are only expensive because of government-granted patent monopolies. The free market price is typically less than 10 percent of the patent monopoly price and often less than 1 percent. The generic versions of drugs that sell for tens of thousands of dollars or even hundreds of thousands of dollars in the United States often cost just a few hundred dollars.

A number of Democratic senators have proposed legislation that would have the government pay for research upfront. This would mean that new drugs could sell at generic prices. This would eliminate all the corruption associated with the current system, including the incentive to lie about the effectiveness and safety of drugs. It would likely save more than $380 billion a year (just under 2.0 percent of GDP) on prescription drug expenditures.

The Washington Post reported on new health care spending projections from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) which show spending rising to almost 20 percent of GDP by 2026 compared to 17.9 percent in 2016. It is worth noting that these projections have consistently overstated cost growth. For example in 2005, CMS projected that health care costs would rise to 19.6 percent of GDP in 2016.

The piece also notes that prescription drugs are projected to be the most rapidly growing component of health care costs. It is worth mentioning that prescription drugs are only expensive because of government-granted patent monopolies. The free market price is typically less than 10 percent of the patent monopoly price and often less than 1 percent. The generic versions of drugs that sell for tens of thousands of dollars or even hundreds of thousands of dollars in the United States often cost just a few hundred dollars.

A number of Democratic senators have proposed legislation that would have the government pay for research upfront. This would mean that new drugs could sell at generic prices. This would eliminate all the corruption associated with the current system, including the incentive to lie about the effectiveness and safety of drugs. It would likely save more than $380 billion a year (just under 2.0 percent of GDP) on prescription drug expenditures.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión