As someone whose mother took him to Bargain Town (the original name for Toys ‘R’ Us) when I was a little kid, it’s hard not to feel sad to see Toys ‘R’ Us being liquidated. There were obviously many factors involved in the company’s collapse. It faced serious competition from first Walmart and then Amazon and other internet retailers in a rapidly changing environment.

This situation would have made prospering difficult for Toys ‘R’ Us in any case, but its takeover by private equity was what really pounded the nails in the coffin. In 2005, two private equity companies took over the company and immediately loaded it up with debt, a standard practice for private equity.

This can be a profitable strategy, since the interest payments are tax-deductible for the company, whereas dividends paid out to shareholders are not. Private equity companies also often use debt to pay out dividends to themselves so they can quickly recover much of what they spent to purchase the company. (To get the full story on private equity read Private Equity at Work: When Wall Street Manages Main Street, by my colleague Eileen Appelbaum and Rose Batt.)

Essentially, what the debt does is create a highly leveraged bet where the private equity company stands to make a huge return on its investment if the company survives and can again be taken public. If it fails, as was the case with Toys ‘R’ Us, they may still come out ahead from the dividend payouts and various management fees charged to the company.

If this strategy is good for private equity, then who ends up as losers? Well, most obviously the 33,000 workers who stand to lose their jobs with the liquidation. Apparently, there is a possibility that some of the stores may be sold off and operated by a competitor, so perhaps some of these jobs can be saved, but clearly, most of these people will be looking for new work.

The people who lent Toys ‘R’ Us money also stand to lose, as the bankruptcy likely means they will only be repaid a small part of their loans. There should not be too many tears shed here. Presumably, the lenders understand the risk of giving money to a highly indebted company. They should have charged a high-interest rate to compensate for the risk.

The more serious issue is with the inadvertent creditors. These are the suppliers that may have sold the company merchandise on credit. It may also include companies that provide services to Toys ‘R’ Us, such as a trucking company or a cleaning service. These companies didn’t intend to make loans to Toys ‘R’ Us, they just were following normal business practices in providing goods and services in advance of payment. Perhaps they should have been more careful, given the financial situation of Toys ‘R’ Us, but businesses don’t always do credit checks on their customers in advance of making sales. Anyhow, in addition to losing an important customer, these suppliers are likely to see big losses from the money owed to them by Toys ‘R’ Us.

There are things that can be done to rein in private equity. First, the asymmetric treatment of interest and dividend payments in the tax code makes little sense. One of the positive items in the Republican tax bill last fall was a cap on the deductibility of interest at 30 percent of profits. (The bill includes the Donald J. Trump exception for real estate.) This should provide less incentive for private equity companies to go the high debt route in the future.

It is also important to follow the assets. In many cases, the private equity company effectively shifts the profitable assets, like real estate, to other corporations under their control, so that creditors have no assets to seize. Bankruptcy courts have to police this shuffle the asset routine and hold the private equity company itself liable when a company under its control has not been properly compensated for the loss of an asset.

Most importantly, long-term workers should be compensated for their time with the company. The United States is the only wealthy country that allows workers to be fired at will with no compensation.

Some reasonable compensation, say two weeks of pay per year of work, would provide long-term workers with help transitioning to new employment. More importantly, it changes the incentive for companies. If they know they will have to pay 40 weeks of severance pay to a worker who has been with the company for 20 years, they will think more about keeping this worker on the payroll and training them to be more productive, rather than just dumping her.

While the Republican Congress is not likely to be interested in taking a step like this to help workers, severance pay is something that can be put in place at the state level. (Montana already has a law requiring compensation for long-term workers who are dismissed without cause.) More progressive states like California, New York, or Washington can take the lead here, as they have on other issues.

As long as we will have a capitalist economy, we will have companies that go out of business. But we should not structure our tax and bankruptcy laws to make going out of business profitable. And, we should ensure that workers end up treated fairly in the process.

As someone whose mother took him to Bargain Town (the original name for Toys ‘R’ Us) when I was a little kid, it’s hard not to feel sad to see Toys ‘R’ Us being liquidated. There were obviously many factors involved in the company’s collapse. It faced serious competition from first Walmart and then Amazon and other internet retailers in a rapidly changing environment.

This situation would have made prospering difficult for Toys ‘R’ Us in any case, but its takeover by private equity was what really pounded the nails in the coffin. In 2005, two private equity companies took over the company and immediately loaded it up with debt, a standard practice for private equity.

This can be a profitable strategy, since the interest payments are tax-deductible for the company, whereas dividends paid out to shareholders are not. Private equity companies also often use debt to pay out dividends to themselves so they can quickly recover much of what they spent to purchase the company. (To get the full story on private equity read Private Equity at Work: When Wall Street Manages Main Street, by my colleague Eileen Appelbaum and Rose Batt.)

Essentially, what the debt does is create a highly leveraged bet where the private equity company stands to make a huge return on its investment if the company survives and can again be taken public. If it fails, as was the case with Toys ‘R’ Us, they may still come out ahead from the dividend payouts and various management fees charged to the company.

If this strategy is good for private equity, then who ends up as losers? Well, most obviously the 33,000 workers who stand to lose their jobs with the liquidation. Apparently, there is a possibility that some of the stores may be sold off and operated by a competitor, so perhaps some of these jobs can be saved, but clearly, most of these people will be looking for new work.

The people who lent Toys ‘R’ Us money also stand to lose, as the bankruptcy likely means they will only be repaid a small part of their loans. There should not be too many tears shed here. Presumably, the lenders understand the risk of giving money to a highly indebted company. They should have charged a high-interest rate to compensate for the risk.

The more serious issue is with the inadvertent creditors. These are the suppliers that may have sold the company merchandise on credit. It may also include companies that provide services to Toys ‘R’ Us, such as a trucking company or a cleaning service. These companies didn’t intend to make loans to Toys ‘R’ Us, they just were following normal business practices in providing goods and services in advance of payment. Perhaps they should have been more careful, given the financial situation of Toys ‘R’ Us, but businesses don’t always do credit checks on their customers in advance of making sales. Anyhow, in addition to losing an important customer, these suppliers are likely to see big losses from the money owed to them by Toys ‘R’ Us.

There are things that can be done to rein in private equity. First, the asymmetric treatment of interest and dividend payments in the tax code makes little sense. One of the positive items in the Republican tax bill last fall was a cap on the deductibility of interest at 30 percent of profits. (The bill includes the Donald J. Trump exception for real estate.) This should provide less incentive for private equity companies to go the high debt route in the future.

It is also important to follow the assets. In many cases, the private equity company effectively shifts the profitable assets, like real estate, to other corporations under their control, so that creditors have no assets to seize. Bankruptcy courts have to police this shuffle the asset routine and hold the private equity company itself liable when a company under its control has not been properly compensated for the loss of an asset.

Most importantly, long-term workers should be compensated for their time with the company. The United States is the only wealthy country that allows workers to be fired at will with no compensation.

Some reasonable compensation, say two weeks of pay per year of work, would provide long-term workers with help transitioning to new employment. More importantly, it changes the incentive for companies. If they know they will have to pay 40 weeks of severance pay to a worker who has been with the company for 20 years, they will think more about keeping this worker on the payroll and training them to be more productive, rather than just dumping her.

While the Republican Congress is not likely to be interested in taking a step like this to help workers, severance pay is something that can be put in place at the state level. (Montana already has a law requiring compensation for long-term workers who are dismissed without cause.) More progressive states like California, New York, or Washington can take the lead here, as they have on other issues.

As long as we will have a capitalist economy, we will have companies that go out of business. But we should not structure our tax and bankruptcy laws to make going out of business profitable. And, we should ensure that workers end up treated fairly in the process.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

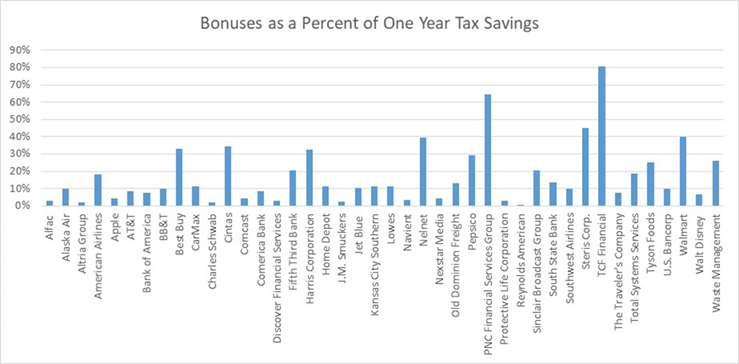

Many large companies managed to get some good publicity by announcing bonuses for their workers which they said were the fruits of the tax cuts. We, of course, have no way of knowing the extent to which these bonuses were due to the tax cut or were simply a story of companies trying to retain workers in a tighter labor market.

In that context, it would have been better to see pay increases, which presumably will be in place in subsequent years and provide a higher basis for future pay raises. Of course, some companies did announce that they were raising workers pay also, in addition to some who improved retirement and other benefits.

All of that is good, but it does still miss the point of the Republican tax cut story. Their claims of workers getting $4,000 to $9,000 more in annual income did not depend on companies sharing their tax cuts. Rather it is a story that depends on a tidal wave of new investment increasing productivity. Higher productivity five or ten years out is supposed to mean higher wages.

The early returns on the investment-productivity story are not good, but we still can’t say anything conclusive on the investment boom story. But we can join in the game to see what share of company tax cuts are being shared with workers through the much-hyped bonuses.

I did a quick calculation where I used the income and taxes reported in companies’ 2016 annual report and compared it to what they would be paying at the new 21 percent tax rate, to calculate companies’ tax savings. This likely understates the tax savings since many companies will undoubtedly find ways to pay less than the 21 percent statutory rate. Also, presumably their profits and therefore savings will be higher in 2018 than in 2016. It is also important to remember that their tax savings will be an annual deal, recurring for the indefinite future, whereas the workers’ bonuses are a one-time event.

The figure below gives the picture.

Source: Author’s calculations.

The bonus figures are taken from The Americans for Tax Reform “list of tax reform good news.” I did make some assumptions to get the ratios. For example, in the case of Walmart, they reported giving a maximum bonus of $1,000 which went to a full-time worker who had been with the company for 20 years. I assumed that the average bonus for its 1.6 million workers would be half of this amount. I generally tried to be generous in these assumptions.

Addendum:

I forget to mention that the Republicans effectively paid companies to announce bonuses before the end of last year. A bonus announced in 2017 could be deducted against 2017 profits, even though it may not be paid until 2018. This makes a big difference since companies faced a 35 percent tax rate in 2017, compared with a 21 percent tax rate in 2018.

This means, for example, that the $800 million in bonuses that Walmart is promising only cost the company only cost the company $520 million (65 percent of $800 million) because they announced it in 2017. If they had waited until 2018 the bonuses would have cost them $632 million (79 percent of $800 million). In effect, Walmart was paid $112 million to announce its bonuses before the end of 2017. This is the same story for any company considering bonuses for its workers.

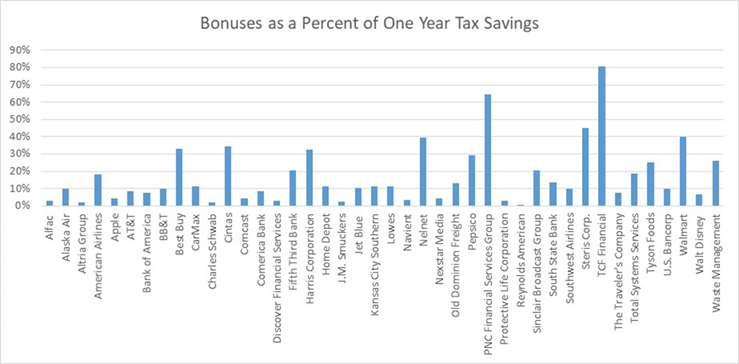

Many large companies managed to get some good publicity by announcing bonuses for their workers which they said were the fruits of the tax cuts. We, of course, have no way of knowing the extent to which these bonuses were due to the tax cut or were simply a story of companies trying to retain workers in a tighter labor market.

In that context, it would have been better to see pay increases, which presumably will be in place in subsequent years and provide a higher basis for future pay raises. Of course, some companies did announce that they were raising workers pay also, in addition to some who improved retirement and other benefits.

All of that is good, but it does still miss the point of the Republican tax cut story. Their claims of workers getting $4,000 to $9,000 more in annual income did not depend on companies sharing their tax cuts. Rather it is a story that depends on a tidal wave of new investment increasing productivity. Higher productivity five or ten years out is supposed to mean higher wages.

The early returns on the investment-productivity story are not good, but we still can’t say anything conclusive on the investment boom story. But we can join in the game to see what share of company tax cuts are being shared with workers through the much-hyped bonuses.

I did a quick calculation where I used the income and taxes reported in companies’ 2016 annual report and compared it to what they would be paying at the new 21 percent tax rate, to calculate companies’ tax savings. This likely understates the tax savings since many companies will undoubtedly find ways to pay less than the 21 percent statutory rate. Also, presumably their profits and therefore savings will be higher in 2018 than in 2016. It is also important to remember that their tax savings will be an annual deal, recurring for the indefinite future, whereas the workers’ bonuses are a one-time event.

The figure below gives the picture.

Source: Author’s calculations.

The bonus figures are taken from The Americans for Tax Reform “list of tax reform good news.” I did make some assumptions to get the ratios. For example, in the case of Walmart, they reported giving a maximum bonus of $1,000 which went to a full-time worker who had been with the company for 20 years. I assumed that the average bonus for its 1.6 million workers would be half of this amount. I generally tried to be generous in these assumptions.

Addendum:

I forget to mention that the Republicans effectively paid companies to announce bonuses before the end of last year. A bonus announced in 2017 could be deducted against 2017 profits, even though it may not be paid until 2018. This makes a big difference since companies faced a 35 percent tax rate in 2017, compared with a 21 percent tax rate in 2018.

This means, for example, that the $800 million in bonuses that Walmart is promising only cost the company only cost the company $520 million (65 percent of $800 million) because they announced it in 2017. If they had waited until 2018 the bonuses would have cost them $632 million (79 percent of $800 million). In effect, Walmart was paid $112 million to announce its bonuses before the end of 2017. This is the same story for any company considering bonuses for its workers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is amazing how otherworldly seemingly intelligent people can sometimes be. The NYT ran a column by Alec Schierenbeck arguing that fines for things like parking and traffic violations should be progressive.

The point is that a $150 speeding ticket is no big deal to a high-priced doctor or lawyer, whereas it is a huge deal to a mother working at a near minimum wage job. This fine may be an impossible for burden for the latter, possibly leading to eviction or even imprisonment in some cases for failing to make court appearances connected with non-payment.

Schierenbeck is 100 percent right in this basic point, but in a country where the justice system is already so unbelievably tilted to favor the rich, the idea that we would make fines income-based is hopelessly utopian. Perhaps Schierenbeck is not old enough to remember the housing crash and the resulting financial crisis. This literally cost the country trillions in lost output, as millions lost their jobs and homes.

People in the financial industry committed serious crimes. They passed along mortgages they knew to be fraudulent in mortgage-backed securities. The credit rating agencies blessed these mortgage-backed securities as investment grade even though they knew they were garbage. No one went to jail because our country doesn’t put rich people who commit financial crimes in jail.

And, this wasn’t a one-off event. Let’s see Donald Trump or Jared Kushner’s tax returns. I would be willing to bet that there are bogus deductions that rip off more money from the taxpayers than the amounts that many convicted small thieves are sitting in jail for. And, this is a bi-partisan story. I’m sure there is lots of garbage on Robert Rubin’s tax returns or Tony James’.

We live in a country where it is standard practice for rich people to get away with breaking the law in really big ways and facing, at worst, a slap on the wrist if they get caught. So yes, it would be fairer if the fines for minor offenses were income-based, but we don’t live in a country where fairness between the rich and poor is taken seriously, and it is an insult to NYT readers to pretend we are.

It is amazing how otherworldly seemingly intelligent people can sometimes be. The NYT ran a column by Alec Schierenbeck arguing that fines for things like parking and traffic violations should be progressive.

The point is that a $150 speeding ticket is no big deal to a high-priced doctor or lawyer, whereas it is a huge deal to a mother working at a near minimum wage job. This fine may be an impossible for burden for the latter, possibly leading to eviction or even imprisonment in some cases for failing to make court appearances connected with non-payment.

Schierenbeck is 100 percent right in this basic point, but in a country where the justice system is already so unbelievably tilted to favor the rich, the idea that we would make fines income-based is hopelessly utopian. Perhaps Schierenbeck is not old enough to remember the housing crash and the resulting financial crisis. This literally cost the country trillions in lost output, as millions lost their jobs and homes.

People in the financial industry committed serious crimes. They passed along mortgages they knew to be fraudulent in mortgage-backed securities. The credit rating agencies blessed these mortgage-backed securities as investment grade even though they knew they were garbage. No one went to jail because our country doesn’t put rich people who commit financial crimes in jail.

And, this wasn’t a one-off event. Let’s see Donald Trump or Jared Kushner’s tax returns. I would be willing to bet that there are bogus deductions that rip off more money from the taxpayers than the amounts that many convicted small thieves are sitting in jail for. And, this is a bi-partisan story. I’m sure there is lots of garbage on Robert Rubin’s tax returns or Tony James’.

We live in a country where it is standard practice for rich people to get away with breaking the law in really big ways and facing, at worst, a slap on the wrist if they get caught. So yes, it would be fairer if the fines for minor offenses were income-based, but we don’t live in a country where fairness between the rich and poor is taken seriously, and it is an insult to NYT readers to pretend we are.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It was widely reported that Donald Trump confronted Canada’s prime minister Justin Trudeau over his country’s trade surplus with the United States. Trump was mocked in these stories since they claimed that Canada actually has a trade deficit with the United States. When confronted with this alleged fact, Trump boasted about just making up numbers in his exchange with Canada’s prime minister.

It turns out that Trump is actually correct about Canada’s trade surplus with the United States. The Commerce Department data that reporters used to show a trade surplus includes re-exports. These are items that are shipped through the United States, but are not produced in the United States. For example, if a German car company ships 1000 cars through New York, and 100 of these end up in Canada, the 100 cars would be counted as US exports even though they were not produced in the United States.

The United Nations has a database which separates out re-exports. When this is done, Canada’s deficit turns into a surplus in the neighborhood of $20–$30 billion. This means that Trump was correct in his charge.

To be clear, this doesn’t excuse the president meeting another head of government and not knowing what he is talking about. Nor does it necessarily mean Canada is doing anything wrong because it has a trade surplus with the United States. (We could address this by reducing our oil consumption.) Donald Trump may not care about getting his numbers right but the rest of us should.

Thanks to Lori Wallach of Public Citizen for calling my attention to this point.

It was widely reported that Donald Trump confronted Canada’s prime minister Justin Trudeau over his country’s trade surplus with the United States. Trump was mocked in these stories since they claimed that Canada actually has a trade deficit with the United States. When confronted with this alleged fact, Trump boasted about just making up numbers in his exchange with Canada’s prime minister.

It turns out that Trump is actually correct about Canada’s trade surplus with the United States. The Commerce Department data that reporters used to show a trade surplus includes re-exports. These are items that are shipped through the United States, but are not produced in the United States. For example, if a German car company ships 1000 cars through New York, and 100 of these end up in Canada, the 100 cars would be counted as US exports even though they were not produced in the United States.

The United Nations has a database which separates out re-exports. When this is done, Canada’s deficit turns into a surplus in the neighborhood of $20–$30 billion. This means that Trump was correct in his charge.

To be clear, this doesn’t excuse the president meeting another head of government and not knowing what he is talking about. Nor does it necessarily mean Canada is doing anything wrong because it has a trade surplus with the United States. (We could address this by reducing our oil consumption.) Donald Trump may not care about getting his numbers right but the rest of us should.

Thanks to Lori Wallach of Public Citizen for calling my attention to this point.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It would be interesting to know how the paper made that determination, but it referred to “China’s theft of American intellectual property” as a matter of fact. China is bound by the TRIPS provisions in the WTO, but there are many different interpretations of these rules.

Perhaps the NYT has analyzed China’s practices and determined they violate TRIPS. If so, they should share this analysis with its readers.

It is also worth noting that the enforcement of intellectual property rules in China is a factor increasing inequality. The overwhelming beneficiaries of these rules are at the top end of the income distribution. On the other hand, if China doesn’t have to pay royalties and licensing fees to Bill Gates and his ilk, the items China produces will be available for lower costs to US consumers.

This is the same argument that “free traders” always make about how tariffs are bad, except the beneficiaries from the protection of intellectual property are almost exclusively people at the top end of the income ladder, and there is much more money involved than with tariffs. Of course, if we have longer and stronger protections for intellectual property then liberal foundations can give more money to economists to figure out the causes of inequality.

It would be interesting to know how the paper made that determination, but it referred to “China’s theft of American intellectual property” as a matter of fact. China is bound by the TRIPS provisions in the WTO, but there are many different interpretations of these rules.

Perhaps the NYT has analyzed China’s practices and determined they violate TRIPS. If so, they should share this analysis with its readers.

It is also worth noting that the enforcement of intellectual property rules in China is a factor increasing inequality. The overwhelming beneficiaries of these rules are at the top end of the income distribution. On the other hand, if China doesn’t have to pay royalties and licensing fees to Bill Gates and his ilk, the items China produces will be available for lower costs to US consumers.

This is the same argument that “free traders” always make about how tariffs are bad, except the beneficiaries from the protection of intellectual property are almost exclusively people at the top end of the income ladder, and there is much more money involved than with tariffs. Of course, if we have longer and stronger protections for intellectual property then liberal foundations can give more money to economists to figure out the causes of inequality.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A lot of folks are running around making a big point of the fact that Larry Kudlow, Trump’s new head of the National Economic Council, has gotten a lot of things about the economy wrong, and in particular missed the coming of the Great Recession. For example, here’s Dana Milbank’s column in the Washington Post this morning.

While Kudlow has gotten a lot of things wrong and completely missed the housing bubble and the implications its collapse would have for the economy, he was hardly alone in this category. Just about the whole economics profession was there along with Kudlow, even if they may not have been quite as outspoken in their optimism.

In January of 2008 the Congressional Budget Office, which consciously tries to place itself in the center of professional opinion, projected 1.7 percent economic growth for 2008 and 2.8 percent for 2009. Even a year later, Christina Romer and my friend Jared Bernstein hugely underestimated the severity of the recession in their report outlining President Obama’ stimulus package.

The commentary of the time is full of great lines from distinguished economists. My favorite was when then Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke said that the problems in financial markets will be restricted to the subprime market. After Bear Stearns went under he also famously commented that he didn’t see another Bear Stearns out there. It subsequently turned out that there were nothing but Bear Stearns out there, as virtually the whole banking system faced collapse as trillions of dollars of mortgage debt went bad.

I could go on, but the point is that Kudlow was hardly alone in his mistake here. I spent years being derided by many of the country’s leading economists for suggesting that there was a housing bubble and its collapse could sink the economy. So yes Kudlow really blew it, but so did pretty much the whole economics profession. (Fortunately for economists, economics is not a profession where people are evaluated based on their performance.)

To Kudlow’s credit, he was at least prepared to allow people like me, who warned of the bubble, appear on his show. That was not the case with Mr. Milbank’s paper, The Washington Post, which pretty much excluded anyone warning of the bubble until after it burst. (The Post was busy hyping fears about the budget deficit.)

A lot of folks are running around making a big point of the fact that Larry Kudlow, Trump’s new head of the National Economic Council, has gotten a lot of things about the economy wrong, and in particular missed the coming of the Great Recession. For example, here’s Dana Milbank’s column in the Washington Post this morning.

While Kudlow has gotten a lot of things wrong and completely missed the housing bubble and the implications its collapse would have for the economy, he was hardly alone in this category. Just about the whole economics profession was there along with Kudlow, even if they may not have been quite as outspoken in their optimism.

In January of 2008 the Congressional Budget Office, which consciously tries to place itself in the center of professional opinion, projected 1.7 percent economic growth for 2008 and 2.8 percent for 2009. Even a year later, Christina Romer and my friend Jared Bernstein hugely underestimated the severity of the recession in their report outlining President Obama’ stimulus package.

The commentary of the time is full of great lines from distinguished economists. My favorite was when then Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke said that the problems in financial markets will be restricted to the subprime market. After Bear Stearns went under he also famously commented that he didn’t see another Bear Stearns out there. It subsequently turned out that there were nothing but Bear Stearns out there, as virtually the whole banking system faced collapse as trillions of dollars of mortgage debt went bad.

I could go on, but the point is that Kudlow was hardly alone in his mistake here. I spent years being derided by many of the country’s leading economists for suggesting that there was a housing bubble and its collapse could sink the economy. So yes Kudlow really blew it, but so did pretty much the whole economics profession. (Fortunately for economists, economics is not a profession where people are evaluated based on their performance.)

To Kudlow’s credit, he was at least prepared to allow people like me, who warned of the bubble, appear on his show. That was not the case with Mr. Milbank’s paper, The Washington Post, which pretty much excluded anyone warning of the bubble until after it burst. (The Post was busy hyping fears about the budget deficit.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Many economists, including those at the I.M.F., have concluded that the austerity policies imposed on the euro zone by Germany cost millions of jobs and trillions of dollars of output over the last decade. But the NYT dismisses this assessment and tells readers that policies moving away from austerity, “could undo economic boom.”

The piece tells readers that reducing restrictions on firing across the eurozone was a major factor in lowering unemployment:

“He also pushed those countries to emulate Germany’s reforms, in particular relaxing restrictions on hiring and firing. Many countries complied, at least to a degree, helping joblessness in the eurozone fall to 8.6 percent in February, down from more than 12 percent in 2013.”

This contradicts much research which finds that restriction on firings have no effect on employment and unemployment. The more likely explanation is that the euro zone eventually did recover from the 2008–2009 recession, in part because the European Central Bank did its best to work around the austerity being imposed by Germany through fiscal policy.

The one cited source for the piece’s conclusion on labor market dynamics is Holger Schmieding, chief economist of Berenberg, a German bank, although the piece does tell us:

“Surveys of business optimism have slipped in recent months after four years of nearly uninterrupted gains. Such pessimism can become self-fulfilling, discouraging businesses from expanding and hiring.”

So, the NYT is unhappy that German workers may have more job security and get back some of their share of economic output. That’s fine, but maybe they should confine these views to the opinion pages.

Many economists, including those at the I.M.F., have concluded that the austerity policies imposed on the euro zone by Germany cost millions of jobs and trillions of dollars of output over the last decade. But the NYT dismisses this assessment and tells readers that policies moving away from austerity, “could undo economic boom.”

The piece tells readers that reducing restrictions on firing across the eurozone was a major factor in lowering unemployment:

“He also pushed those countries to emulate Germany’s reforms, in particular relaxing restrictions on hiring and firing. Many countries complied, at least to a degree, helping joblessness in the eurozone fall to 8.6 percent in February, down from more than 12 percent in 2013.”

This contradicts much research which finds that restriction on firings have no effect on employment and unemployment. The more likely explanation is that the euro zone eventually did recover from the 2008–2009 recession, in part because the European Central Bank did its best to work around the austerity being imposed by Germany through fiscal policy.

The one cited source for the piece’s conclusion on labor market dynamics is Holger Schmieding, chief economist of Berenberg, a German bank, although the piece does tell us:

“Surveys of business optimism have slipped in recent months after four years of nearly uninterrupted gains. Such pessimism can become self-fulfilling, discouraging businesses from expanding and hiring.”

So, the NYT is unhappy that German workers may have more job security and get back some of their share of economic output. That’s fine, but maybe they should confine these views to the opinion pages.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Thomas Friedman used his column today to trash Trump for protecting old-line industries like steel and aluminum and argued instead that US trade policy should be, “[…]focused on protecting what we do best — high-value-added manufacturing and intellectual property.” In this vein, he argued for rejoining the Trans-Pacific Partnership and very high tariffs on China unless it respects our protectionist policies in these areas. Oh yeah, Friedman also wants to toss a few bones to the less-educated workers who might lose jobs but will pay higher prices for prescription drugs, software, and a wide range of other items with Friedman’s agenda.

Just to get our eyes on the ball, if anyone were approaching these issues seriously, they would be asking how much additional innovation we get for how much additional patent and copyright protection. (Anyone seen any analysis on this one?) The question would then be both, is the additional inequality from stronger and longer protections justified by the additional innovation and is there an alternative mechanism (e.g. direct public funding) that could be comparable efficient and yield less inequality. (This is discussed in my [free] book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer, chapter 5.)

For some reason, it seems no one likes to talk about the link between patent and copyright protection and inequality. Remember, Bill Gates would probably still be working for a living without these government-granted monopolies.

Thomas Friedman used his column today to trash Trump for protecting old-line industries like steel and aluminum and argued instead that US trade policy should be, “[…]focused on protecting what we do best — high-value-added manufacturing and intellectual property.” In this vein, he argued for rejoining the Trans-Pacific Partnership and very high tariffs on China unless it respects our protectionist policies in these areas. Oh yeah, Friedman also wants to toss a few bones to the less-educated workers who might lose jobs but will pay higher prices for prescription drugs, software, and a wide range of other items with Friedman’s agenda.

Just to get our eyes on the ball, if anyone were approaching these issues seriously, they would be asking how much additional innovation we get for how much additional patent and copyright protection. (Anyone seen any analysis on this one?) The question would then be both, is the additional inequality from stronger and longer protections justified by the additional innovation and is there an alternative mechanism (e.g. direct public funding) that could be comparable efficient and yield less inequality. (This is discussed in my [free] book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer, chapter 5.)

For some reason, it seems no one likes to talk about the link between patent and copyright protection and inequality. Remember, Bill Gates would probably still be working for a living without these government-granted monopolies.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It seems Germany is suffering from a skills gap also, at least according to Reuters. It told readers:

“Labour shortages in Germany are threatening the whole economy as companies struggle to fill around 1.6 million job vacancies, the DIHK Chambers of Industry and Commerce said on Tuesday.”

According to the OECD, labor compensation rose by just 2.6 percent last year, down from a 2.9 percent rate in 2016. When an item is in short supply, we expect the price to rise. If there is a housing shortage, buyers or renters bid up the price of housing. If employers can’t get workers, then the normal route is to offer higher pay, which will attract workers from competitors.

Apparently, German employers don’t understand basic economics. Their ignorance is apparently jeopardizing the whole economy, according to the DIHK Chambers of Industry and Commerce.

It seems Germany is suffering from a skills gap also, at least according to Reuters. It told readers:

“Labour shortages in Germany are threatening the whole economy as companies struggle to fill around 1.6 million job vacancies, the DIHK Chambers of Industry and Commerce said on Tuesday.”

According to the OECD, labor compensation rose by just 2.6 percent last year, down from a 2.9 percent rate in 2016. When an item is in short supply, we expect the price to rise. If there is a housing shortage, buyers or renters bid up the price of housing. If employers can’t get workers, then the normal route is to offer higher pay, which will attract workers from competitors.

Apparently, German employers don’t understand basic economics. Their ignorance is apparently jeopardizing the whole economy, according to the DIHK Chambers of Industry and Commerce.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Apparently, America’s small business owners are too dumb to realize how great the tax cuts were. The Trump administration told us that the corporate tax cuts would lead to a massive boom in investment which would increase the capital stock by one third above the baseline projection. But for some reason, the nation’s businesses haven’t gotten the message.

The National Federation of Independent Businesses released its February survey of its members this morning. The survey showed (page 29) that 29 percent of businesses expect to make a capital expenditure in the next 3 to 6 months, the same percentage as in January. This is somewhat higher than the 26 percent reported for February of 2017, but below the 32 percent reported for August of last year. It’s also the same as the 29 percent reading reported back in August of 2014 when a Kenyan socialist was in the White House.

In other words, there is no evidence here of any uptick in investment whatsoever and certainly not of the explosive increase promised by the Trump administration. Maybe if Trump did some more tweeting on the issue it would help.

Apparently, America’s small business owners are too dumb to realize how great the tax cuts were. The Trump administration told us that the corporate tax cuts would lead to a massive boom in investment which would increase the capital stock by one third above the baseline projection. But for some reason, the nation’s businesses haven’t gotten the message.

The National Federation of Independent Businesses released its February survey of its members this morning. The survey showed (page 29) that 29 percent of businesses expect to make a capital expenditure in the next 3 to 6 months, the same percentage as in January. This is somewhat higher than the 26 percent reported for February of 2017, but below the 32 percent reported for August of last year. It’s also the same as the 29 percent reading reported back in August of 2014 when a Kenyan socialist was in the White House.

In other words, there is no evidence here of any uptick in investment whatsoever and certainly not of the explosive increase promised by the Trump administration. Maybe if Trump did some more tweeting on the issue it would help.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión