Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

If anyone took the rationale for the Republican tax cuts seriously, the key measure is investment. The promise was that lower corporate tax rates would provide a huge incentive for investment, causing the capital stock to increase by roughly one-third over its baseline growth path within a decade.

As I have pointed out, the early numbers were not good. Capital goods orders fell in both December and January. The National Federation of Independent Businesses reports no notable uptick in the investment plans of its members.

The new numbers from the Commerce Department today look a bit better. Overall capital goods orders were up 4.5 percent in February from January levels. If we pull out erratic aircraft orders there was still an increase of 1.8 percent. That’s a pretty good one month jump, but it follows declines in the last two months that totaled 0.9 percent. That leaves growth of 0.9 percent in the last three months or 0.3 percent a month.

The increase over the last year is 7.4 percent. That is roughly the same as the rate of growth before the tax cut. In other words, we’re pretty much on the baseline path, with no obvious tax cut induced jump.

This may not be a great story for tax cut proponents, but at least investment is now moving in the right direction.

If anyone took the rationale for the Republican tax cuts seriously, the key measure is investment. The promise was that lower corporate tax rates would provide a huge incentive for investment, causing the capital stock to increase by roughly one-third over its baseline growth path within a decade.

As I have pointed out, the early numbers were not good. Capital goods orders fell in both December and January. The National Federation of Independent Businesses reports no notable uptick in the investment plans of its members.

The new numbers from the Commerce Department today look a bit better. Overall capital goods orders were up 4.5 percent in February from January levels. If we pull out erratic aircraft orders there was still an increase of 1.8 percent. That’s a pretty good one month jump, but it follows declines in the last two months that totaled 0.9 percent. That leaves growth of 0.9 percent in the last three months or 0.3 percent a month.

The increase over the last year is 7.4 percent. That is roughly the same as the rate of growth before the tax cut. In other words, we’re pretty much on the baseline path, with no obvious tax cut induced jump.

This may not be a great story for tax cut proponents, but at least investment is now moving in the right direction.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is striking how the media universally accept the idea that patent and copyright monopolies are somehow free trade. We get that the people who own and control major news outlets like these forms of protection, but it is incredibly dishonest to claim that they are somehow free trade.

We get this story yet again in an NYT piece complaining about China’s “theft” of intellectual property while telling readers about how Trump’s proposed tariffs show his:

“[…]resolve to turn away from a decades-long move toward open markets and integrated world economies and toward a more starkly protectionist approach that erects barriers around a Fortress America.”

While we are supposed to be alarmed about tariffs of 10 percent and 25 percent on steel and aluminum, patents and copyrights are effectively tariffs of many thousand percents, often raising the price of protected items tenfold or even a hundredfold. The economic impact of increased protectionism of this type has been enormous.

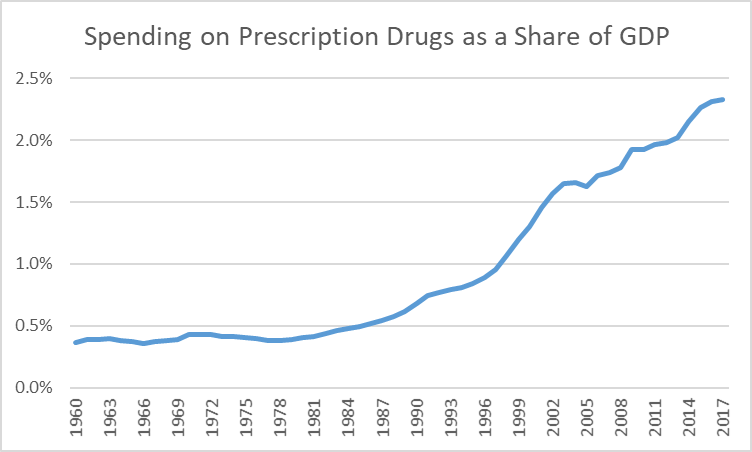

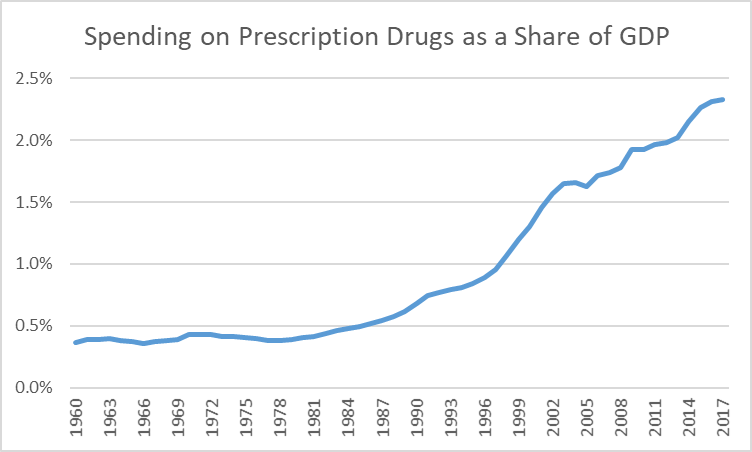

This can be seen clearly in the case of prescription drugs, where spending went from around 0.4 percent of GDP in the 1960s and 1970s to 2.4 percent of GDP ($450 billion) in 2017, as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Since drugs are almost invariably cheap to manufacture, we would likely be spending less than $80 billion a year in the absence of patent and related protections, implying a cost of protectionism of more than $370 billion, and this is just from drug patents. Adding in costs in medical equipment, software, and other areas would likely more than double and quite possibly triple this amount.

The supporters of this protectionism argue that we need patent and copyright monopolies to provide an incentive for innovation and creative work. However, there are two major flaws in this argument.

First, while these monopolies are one way to finance research, they are not the only way. There are other mechanisms, such as direct government funding (we already spend more than $30 billion a year on biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health). Given the enormous cost associated with this protectionism, it would be reasonable to be debating the relative merits of alternatives. (See also Chapter 5 of Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

The other point is even simpler. We have been making patent and copyright protection stronger and longer for the last four decades. We know that this shifts more money from the rest of us to those who benefit from these protections. Even if we decide that these mechanisms are the best way to finance innovation and creative work, it does not mean that making them stronger and longer is always justified.

We should be asking the question of how much additional innovation or creative work do we get for an increment to strengthen and lengthen. This debate never takes place.

This creates the absurd situation where we put in place policies that are designed to transfer money from the rest of us to people like Bill Gates and then we wonder why we have so much income inequality. And the best part of the story is that some of the big gainers from these protections will even finance research as to why we have so much inequality, as long as it doesn’t ask questions about patent and copyright protection.

It is striking how the media universally accept the idea that patent and copyright monopolies are somehow free trade. We get that the people who own and control major news outlets like these forms of protection, but it is incredibly dishonest to claim that they are somehow free trade.

We get this story yet again in an NYT piece complaining about China’s “theft” of intellectual property while telling readers about how Trump’s proposed tariffs show his:

“[…]resolve to turn away from a decades-long move toward open markets and integrated world economies and toward a more starkly protectionist approach that erects barriers around a Fortress America.”

While we are supposed to be alarmed about tariffs of 10 percent and 25 percent on steel and aluminum, patents and copyrights are effectively tariffs of many thousand percents, often raising the price of protected items tenfold or even a hundredfold. The economic impact of increased protectionism of this type has been enormous.

This can be seen clearly in the case of prescription drugs, where spending went from around 0.4 percent of GDP in the 1960s and 1970s to 2.4 percent of GDP ($450 billion) in 2017, as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Since drugs are almost invariably cheap to manufacture, we would likely be spending less than $80 billion a year in the absence of patent and related protections, implying a cost of protectionism of more than $370 billion, and this is just from drug patents. Adding in costs in medical equipment, software, and other areas would likely more than double and quite possibly triple this amount.

The supporters of this protectionism argue that we need patent and copyright monopolies to provide an incentive for innovation and creative work. However, there are two major flaws in this argument.

First, while these monopolies are one way to finance research, they are not the only way. There are other mechanisms, such as direct government funding (we already spend more than $30 billion a year on biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health). Given the enormous cost associated with this protectionism, it would be reasonable to be debating the relative merits of alternatives. (See also Chapter 5 of Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.)

The other point is even simpler. We have been making patent and copyright protection stronger and longer for the last four decades. We know that this shifts more money from the rest of us to those who benefit from these protections. Even if we decide that these mechanisms are the best way to finance innovation and creative work, it does not mean that making them stronger and longer is always justified.

We should be asking the question of how much additional innovation or creative work do we get for an increment to strengthen and lengthen. This debate never takes place.

This creates the absurd situation where we put in place policies that are designed to transfer money from the rest of us to people like Bill Gates and then we wonder why we have so much income inequality. And the best part of the story is that some of the big gainers from these protections will even finance research as to why we have so much inequality, as long as it doesn’t ask questions about patent and copyright protection.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Not deliberately of course, but the NYT had this great piece on how the junk food industry is trying to limit required warnings on junk food as part a renegotiated NAFTA. The issue is that our trading partners are looking to take measures to discourage people from eating foods that are high in sugar, fat, and salt. Several cities and states are considering similar measures. The junk food industry is looking to block such measures by getting a ban included in the new NAFTA.

If you’re wondering what this has to do with free trade, the answer is nothing. However, it is a beautiful example of an industry working to use a trade agreement to subvert the democratic process to advance its interests in a trade deal. If the junk food industry gets its way, the resulting pact will then be blessed as a “free trade” deal. The Washington Post and all the other beacons of the establishment will the proclaim their support for the new NAFTA and denounce opponents as Neanderthal protectionists.

Many of us have long been making the point that recent trade deals like the Trans-Pacific Partnership have little to do with trade and are more about locking in place a business-friendly structure of regulation. But it took the clumsy ineptitude of the Trump Administration to remove any veneer. Thank you, President Trump.

Thanks to Robert Salzberg for corrections from an earlier version.

Not deliberately of course, but the NYT had this great piece on how the junk food industry is trying to limit required warnings on junk food as part a renegotiated NAFTA. The issue is that our trading partners are looking to take measures to discourage people from eating foods that are high in sugar, fat, and salt. Several cities and states are considering similar measures. The junk food industry is looking to block such measures by getting a ban included in the new NAFTA.

If you’re wondering what this has to do with free trade, the answer is nothing. However, it is a beautiful example of an industry working to use a trade agreement to subvert the democratic process to advance its interests in a trade deal. If the junk food industry gets its way, the resulting pact will then be blessed as a “free trade” deal. The Washington Post and all the other beacons of the establishment will the proclaim their support for the new NAFTA and denounce opponents as Neanderthal protectionists.

Many of us have long been making the point that recent trade deals like the Trans-Pacific Partnership have little to do with trade and are more about locking in place a business-friendly structure of regulation. But it took the clumsy ineptitude of the Trump Administration to remove any veneer. Thank you, President Trump.

Thanks to Robert Salzberg for corrections from an earlier version.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes, things could really nasty. In discussing the ways in which China might retaliate against tariffs, the Post told readers:

“China is also the largest foreign holder of U.S. government debt. It holds $1.17 trillion of U.S. Treasury securities, down about $33.5 billion since last August. The U.S. government faces huge borrowing needs, not only to finance new deficits but also to refinance past securities now coming due, so a drop in China’s appetite for that debt could nudge interest rates up in the United States.”

The purchasing of US government bonds by China’s central bank was the main tool through which it propped up the dollar against the yuan. The high-valued dollar makes Chinese goods cheaper relative to US goods, allowing it to run a large trade surplus with the United States.

If China were to sell some of the US bonds it holds, it would raise the value of the yuan, making US goods and services relatively more competitive. This is supposedly what both the Bush and Obama administrations wanted China to do. (I said “supposedly” because this was their public position. I don’t know what happened in their private discussions.)

It is also worth noting that it appears Trump’s major complaint is that he wants more protectionism in the form of stronger patent and copyright protections in China. If he succeeds in this effort, it will mean higher prices for consumers in both the United States and China. For some reason, the Post is not as concerned about the impact of these potential price increases as it is about the impact of higher steel and aluminum prices.

Yes, things could really nasty. In discussing the ways in which China might retaliate against tariffs, the Post told readers:

“China is also the largest foreign holder of U.S. government debt. It holds $1.17 trillion of U.S. Treasury securities, down about $33.5 billion since last August. The U.S. government faces huge borrowing needs, not only to finance new deficits but also to refinance past securities now coming due, so a drop in China’s appetite for that debt could nudge interest rates up in the United States.”

The purchasing of US government bonds by China’s central bank was the main tool through which it propped up the dollar against the yuan. The high-valued dollar makes Chinese goods cheaper relative to US goods, allowing it to run a large trade surplus with the United States.

If China were to sell some of the US bonds it holds, it would raise the value of the yuan, making US goods and services relatively more competitive. This is supposedly what both the Bush and Obama administrations wanted China to do. (I said “supposedly” because this was their public position. I don’t know what happened in their private discussions.)

It is also worth noting that it appears Trump’s major complaint is that he wants more protectionism in the form of stronger patent and copyright protections in China. If he succeeds in this effort, it will mean higher prices for consumers in both the United States and China. For some reason, the Post is not as concerned about the impact of these potential price increases as it is about the impact of higher steel and aluminum prices.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

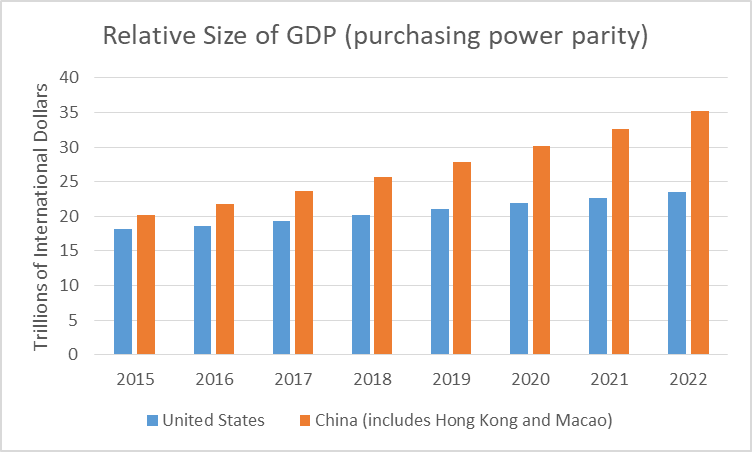

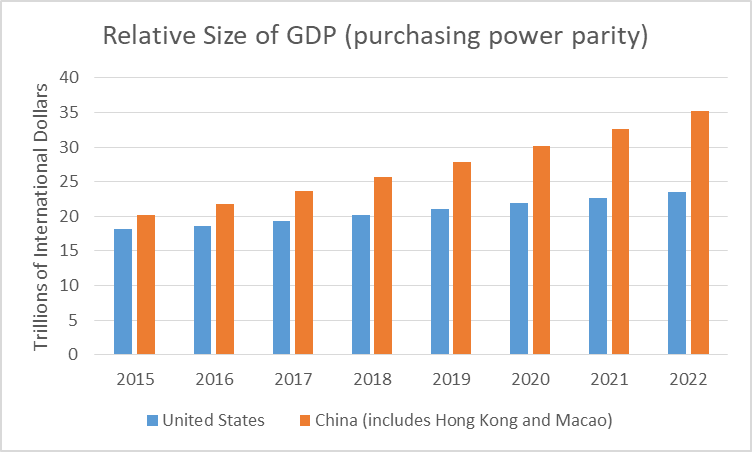

Eswar Prasad makes the case in an NYT column that we should be paying attention to the selection of Yi Gang to head China’s central bank as a result of China’s status as the world’s second-largest economy. Prasad is right about the importance of China’s central bank in the world economy, but it is worth noting that by purchasing power parity (PPP) measures China is already by far the world’s largest economy.

Purchasing power parity calculations of GDP attempt to measure all the goods and services produced by a country with a common set of prices. This means we add up all the cars, tables, haircuts, knee surgeries etc. produced in both the US and China and assume that each item costs the same in both countries.

According to the projections from the IMF, China’s GDP is already 25 percent larger by this measure and will be almost 50 percent larger by the end of the projection period in 2022, as shown in the figure below.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

The US economy is still considerably larger using the exchange rate measure of GDP, but for many purposes, the PPP measure is more appropriate. For example, if we want to gauge the extent to which China’s exports of steel or other items may affect world markets, we would want to know the PPP measure of output, not the exchange rate. Also, if we are looking at living standards, we would want to look at per capita GDP using the PPP measure. (Since China has four times the population of the US, it is still less than one third as rich on a per person basis.)

The PPP measure is also not subject to wild swings like the exchange rate measure. This means, for example, if the Chinese currency were to rise by 20 percent against the dollar, the exchange rate measure of GDP would rise by 20 percent. The PPP measure would not be affected.

Eswar Prasad makes the case in an NYT column that we should be paying attention to the selection of Yi Gang to head China’s central bank as a result of China’s status as the world’s second-largest economy. Prasad is right about the importance of China’s central bank in the world economy, but it is worth noting that by purchasing power parity (PPP) measures China is already by far the world’s largest economy.

Purchasing power parity calculations of GDP attempt to measure all the goods and services produced by a country with a common set of prices. This means we add up all the cars, tables, haircuts, knee surgeries etc. produced in both the US and China and assume that each item costs the same in both countries.

According to the projections from the IMF, China’s GDP is already 25 percent larger by this measure and will be almost 50 percent larger by the end of the projection period in 2022, as shown in the figure below.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

The US economy is still considerably larger using the exchange rate measure of GDP, but for many purposes, the PPP measure is more appropriate. For example, if we want to gauge the extent to which China’s exports of steel or other items may affect world markets, we would want to know the PPP measure of output, not the exchange rate. Also, if we are looking at living standards, we would want to look at per capita GDP using the PPP measure. (Since China has four times the population of the US, it is still less than one third as rich on a per person basis.)

The PPP measure is also not subject to wild swings like the exchange rate measure. This means, for example, if the Chinese currency were to rise by 20 percent against the dollar, the exchange rate measure of GDP would rise by 20 percent. The PPP measure would not be affected.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión