Yes, we know how hard it is for rich people like Jeff Bezos to get by in a free market. That is why George Will argues that taxpayers must subsidize Internet sellers by exempting them from having to collect sales taxes on out of state sales.

While Will argues that the market should decide which retailers win or lose, in fact, he is pushing a position that is 180 degrees opposite the free market one he claims. He is arguing that the state should require brick and mortar stores to collect taxes, but allow Internet sellers to avoid taxes — apparently, because George Will likes Internet sellers. So family-owned book and clothing stores have to collect taxes, but Internet retailers that could be one thousand times their size, do not.

Will seems to think that the prospect of collecting taxes that differ across 12,000 state and local jurisdictions pose an insurmountable problem. Actually, since we have had spreadsheets for four decades, most sellers should be able to easily deal with this issue, and if they can’t, they probably should not be in business. (As a practical matter, no one gives a damn if a seller occasionally makes a mistake in assessing taxes. Getting 99-plus percent right should be easily doable.)

Will also wrongly claims that Amazon collects sales taxes in all 45 states which have them. While Amazon collects taxes on its direct sales, it does not collect taxes on the sales of its “affiliates,” which account for more than 40 percent of its total sales.

As is noted in this piece, Amazon’s founder Jeff Bezos owns the Washington Post. It would be interesting to see if a similarly misleading statement that reflected badly on Amazon would be allowed to stand uncorrected in the paper.

Yes, we know how hard it is for rich people like Jeff Bezos to get by in a free market. That is why George Will argues that taxpayers must subsidize Internet sellers by exempting them from having to collect sales taxes on out of state sales.

While Will argues that the market should decide which retailers win or lose, in fact, he is pushing a position that is 180 degrees opposite the free market one he claims. He is arguing that the state should require brick and mortar stores to collect taxes, but allow Internet sellers to avoid taxes — apparently, because George Will likes Internet sellers. So family-owned book and clothing stores have to collect taxes, but Internet retailers that could be one thousand times their size, do not.

Will seems to think that the prospect of collecting taxes that differ across 12,000 state and local jurisdictions pose an insurmountable problem. Actually, since we have had spreadsheets for four decades, most sellers should be able to easily deal with this issue, and if they can’t, they probably should not be in business. (As a practical matter, no one gives a damn if a seller occasionally makes a mistake in assessing taxes. Getting 99-plus percent right should be easily doable.)

Will also wrongly claims that Amazon collects sales taxes in all 45 states which have them. While Amazon collects taxes on its direct sales, it does not collect taxes on the sales of its “affiliates,” which account for more than 40 percent of its total sales.

As is noted in this piece, Amazon’s founder Jeff Bezos owns the Washington Post. It would be interesting to see if a similarly misleading statement that reflected badly on Amazon would be allowed to stand uncorrected in the paper.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

We get that the Washington Post likes policies that redistribute income upward, but they should be able to argue the case for making the rich richer without turning logic on its head. Apparently, the paper lacks confidence in its position.

This piece also tells readers about a new initiative to promote women’s businesses in Latin America:

“Among the members of the US delegation was Trump’s daughter and adviser, Ivanka, who on Friday morning announced a new $150 million US initiative to help women in Latin America access credit for businesses.”

It would be useful if the piece explained something about this initiative. For example, is this $150 million (0.004 percent of annual federal spending) a grant that will have to be appropriated by Congress? Is it a loan fund, which would also require legislation? Is it a commitment from the Trump Foundation?

If the paper was not prepared to provide any information about this initiative, it should have explained why.

We get that the Washington Post likes policies that redistribute income upward, but they should be able to argue the case for making the rich richer without turning logic on its head. Apparently, the paper lacks confidence in its position.

This piece also tells readers about a new initiative to promote women’s businesses in Latin America:

“Among the members of the US delegation was Trump’s daughter and adviser, Ivanka, who on Friday morning announced a new $150 million US initiative to help women in Latin America access credit for businesses.”

It would be useful if the piece explained something about this initiative. For example, is this $150 million (0.004 percent of annual federal spending) a grant that will have to be appropriated by Congress? Is it a loan fund, which would also require legislation? Is it a commitment from the Trump Foundation?

If the paper was not prepared to provide any information about this initiative, it should have explained why.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

We all know about the skills shortage where Harvard has to pay investment managers millions to lose the school a fortune on its endowment, Facebook can’t find a CEO who can avoid compromising its customers’ privacy, and restaurant managers apparently don’t understand that the way to get more workers is to offer higher pay. The NYT gives us yet another article complaining about labor shortages.

The complaint is that restaurants have small profit margins and therefore can’t afford to offer higher pay to their workers. The way markets are supposed to work is that businesses that can’t afford to pay the market wage go out of business. This is why we don’t still have half of our workforce employed in agriculture. Factories and other urban businesses offered workers better paying opportunities. Most farms could not afford to match the pay and therefore folded often with the farm owner themselves moving to new employment.

This is the story that we should expect to see with restaurants if there really is a labor shortage. We should start to see more rapidly rising wages. The restaurants that can’t pay the market wage go under. That may not be pretty, but that’s capitalism. We tell that to unemployed and low paid workers all the time.

For the record, we aren’t seeing too much by way of rapidly rising wages to date. Over the last year, the pay of production and non-supervisory workers rose 3.2 percent. That’s a bit better than the average of all workers of 2.7 percent, but not the sort of increase that we would expect if there is a serious shortage of labor. It is also worth mentioning that profit margins in business as a whole are near post-war highs as a result of the weak labor market created by the Great Recession, so we should expect some shift back to labor as the labor market tightens.

We all know about the skills shortage where Harvard has to pay investment managers millions to lose the school a fortune on its endowment, Facebook can’t find a CEO who can avoid compromising its customers’ privacy, and restaurant managers apparently don’t understand that the way to get more workers is to offer higher pay. The NYT gives us yet another article complaining about labor shortages.

The complaint is that restaurants have small profit margins and therefore can’t afford to offer higher pay to their workers. The way markets are supposed to work is that businesses that can’t afford to pay the market wage go out of business. This is why we don’t still have half of our workforce employed in agriculture. Factories and other urban businesses offered workers better paying opportunities. Most farms could not afford to match the pay and therefore folded often with the farm owner themselves moving to new employment.

This is the story that we should expect to see with restaurants if there really is a labor shortage. We should start to see more rapidly rising wages. The restaurants that can’t pay the market wage go under. That may not be pretty, but that’s capitalism. We tell that to unemployed and low paid workers all the time.

For the record, we aren’t seeing too much by way of rapidly rising wages to date. Over the last year, the pay of production and non-supervisory workers rose 3.2 percent. That’s a bit better than the average of all workers of 2.7 percent, but not the sort of increase that we would expect if there is a serious shortage of labor. It is also worth mentioning that profit margins in business as a whole are near post-war highs as a result of the weak labor market created by the Great Recession, so we should expect some shift back to labor as the labor market tightens.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In a Washington Post column, Fareed Zakaria gave us yet another of the sermon about how Republicans supported “free trade” before Trump. This is of course not true.

Republicans have done little or nothing to remove the barriers that protect doctors and other highly paid professionals from foreign competition. As a result, our doctors are paid roughly twice as much on average as their counterparts in other wealthy countries, costing us roughly $90 billion a year in higher medical expenses. This swamps the cost of the steel and aluminum tariffs that have gotten “free traders” so upset.

The trade deals have also been quite explicit about increasing protectionism in the form of longer and stronger patent and copyright protections. These protections (as in protectionism) quite explicitly redistribute money from the rest of us to folks like Bill Gates. They are incredibly costly in the sense that they are equivalent to extremely large tariffs, often raising the price of the affected product by a factors of ten or a hundred, the equivalent of tariffs of 1000 or 10,000 percent.

And, there is a huge amount of money involved. In the case of prescription drugs alone, patent and related protections cost us more than $370 billion a year, nearly 2.0 percent of GDP. Real free traders don’t support this protectionism.

It is, of course, convenient for those pushing this agenda of upward redistribution to pretend that it is all just free trade and the free market, but this is nonsense. Unfortunately, you won’t see this point made in the Washington Post. You can read about it in my (free) book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.

In a Washington Post column, Fareed Zakaria gave us yet another of the sermon about how Republicans supported “free trade” before Trump. This is of course not true.

Republicans have done little or nothing to remove the barriers that protect doctors and other highly paid professionals from foreign competition. As a result, our doctors are paid roughly twice as much on average as their counterparts in other wealthy countries, costing us roughly $90 billion a year in higher medical expenses. This swamps the cost of the steel and aluminum tariffs that have gotten “free traders” so upset.

The trade deals have also been quite explicit about increasing protectionism in the form of longer and stronger patent and copyright protections. These protections (as in protectionism) quite explicitly redistribute money from the rest of us to folks like Bill Gates. They are incredibly costly in the sense that they are equivalent to extremely large tariffs, often raising the price of the affected product by a factors of ten or a hundred, the equivalent of tariffs of 1000 or 10,000 percent.

And, there is a huge amount of money involved. In the case of prescription drugs alone, patent and related protections cost us more than $370 billion a year, nearly 2.0 percent of GDP. Real free traders don’t support this protectionism.

It is, of course, convenient for those pushing this agenda of upward redistribution to pretend that it is all just free trade and the free market, but this is nonsense. Unfortunately, you won’t see this point made in the Washington Post. You can read about it in my (free) book, Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

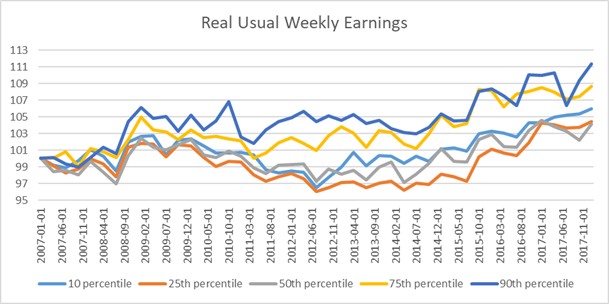

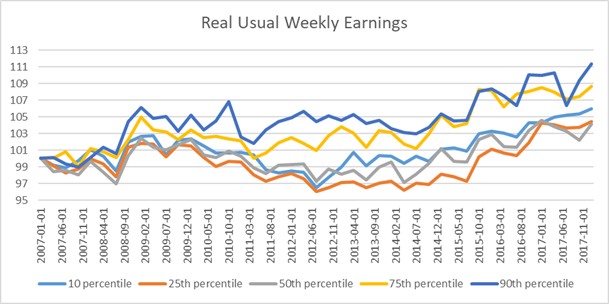

I see my friend Jared Bernstein beat me to the punch in writing up the new data from Usual Weekly Earnings series. As he points out, the story for the median worker — those right at the middle of the income distribution — has not been good over the last year. Donald Trump doesn’t seem to be making American great again for these folks.

Fortunately, there is a bit better story lower down on the income ladder, as we can see in the figure below.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

While real weekly earnings for the median worker have not gone anywhere in the last year, earnings for those at the 25th percentile and the 10th percentile are still headed up. Over the last three years, usual weekly earnings for the 10th percentile worker have risen by 4.8 percent and for 25th percentile worker by 6.5 percent. That’s a pretty good story by almost any standard, although it doesn’t make up for the weakness in the immediate aftermath of the housing crash, much less the three decades of wage stagnation that preceded the Great Recession.

Taking the longer three year period even the earnings for the median worker don’t look bad, rising by 2.9 percent over this period. That’s not great, but in context of 1.0 percent annual productivity growth, at least the median worker is getting her share of the gains. That contrasts with the period from the first quarter of 2007 to the first quarter of 2015 when median earnings rose by a total of just 1.2 percent.

It looks like tight labor markets are acting as expected towards the bottom end of the income ladder. The picture at the median has not been good over the last year or so, but these numbers are erratic. I expect better news in the second quarter at the median, but we’ll see.

I see my friend Jared Bernstein beat me to the punch in writing up the new data from Usual Weekly Earnings series. As he points out, the story for the median worker — those right at the middle of the income distribution — has not been good over the last year. Donald Trump doesn’t seem to be making American great again for these folks.

Fortunately, there is a bit better story lower down on the income ladder, as we can see in the figure below.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

While real weekly earnings for the median worker have not gone anywhere in the last year, earnings for those at the 25th percentile and the 10th percentile are still headed up. Over the last three years, usual weekly earnings for the 10th percentile worker have risen by 4.8 percent and for 25th percentile worker by 6.5 percent. That’s a pretty good story by almost any standard, although it doesn’t make up for the weakness in the immediate aftermath of the housing crash, much less the three decades of wage stagnation that preceded the Great Recession.

Taking the longer three year period even the earnings for the median worker don’t look bad, rising by 2.9 percent over this period. That’s not great, but in context of 1.0 percent annual productivity growth, at least the median worker is getting her share of the gains. That contrasts with the period from the first quarter of 2007 to the first quarter of 2015 when median earnings rose by a total of just 1.2 percent.

It looks like tight labor markets are acting as expected towards the bottom end of the income ladder. The picture at the median has not been good over the last year or so, but these numbers are erratic. I expect better news in the second quarter at the median, but we’ll see.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I’m not kidding, that’s what a column by Isaac Stone Fish in The Washington Post told us. We all know the list of complaints against China. They subsidize their exports of many products, costing US workers their jobs. They deliberately prop up the dollar against the yuan, making US goods and services less competitive. Our companies complain that China takes their intellectual property (doesn’t bother me).

But Fish’s Post column tells us the real problem is that Starbucks and other companies looking to profit from the Chinese consumer market may be hit by a government promoted boycott. I suppose if I had a million dollars of Starbuck’s stock, I would be concerned. After all, their profits could fall by 5–10 percent, lowering the stock price proportionately. (Actually, most non-stockholders gain in this story, as big fans of free trade already know. If China pays less to Starbucks in profits, the dollar will be lower, which means that we will have a lower trade deficit, other things equal.)

For the other 99.99 percent of the American people who don’t own large amounts of stock in Starbucks or similarly situated companies, it doesn’t look like a big deal. Of course, it is interesting to see what sort of arguments The Washington Post takes seriously enough to feature on its opinion page.

I’m not kidding, that’s what a column by Isaac Stone Fish in The Washington Post told us. We all know the list of complaints against China. They subsidize their exports of many products, costing US workers their jobs. They deliberately prop up the dollar against the yuan, making US goods and services less competitive. Our companies complain that China takes their intellectual property (doesn’t bother me).

But Fish’s Post column tells us the real problem is that Starbucks and other companies looking to profit from the Chinese consumer market may be hit by a government promoted boycott. I suppose if I had a million dollars of Starbuck’s stock, I would be concerned. After all, their profits could fall by 5–10 percent, lowering the stock price proportionately. (Actually, most non-stockholders gain in this story, as big fans of free trade already know. If China pays less to Starbucks in profits, the dollar will be lower, which means that we will have a lower trade deficit, other things equal.)

For the other 99.99 percent of the American people who don’t own large amounts of stock in Starbucks or similarly situated companies, it doesn’t look like a big deal. Of course, it is interesting to see what sort of arguments The Washington Post takes seriously enough to feature on its opinion page.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Post asserted that:

“[…]entering into a new TPP could unify Trump with other trading partners and put new pressure on Beijing to either allow more imports into China or risk being alienated by other Asian countries, that would now received new trade benefits as part of the deal.”

Actually, the countries in the TPP will receive relatively few “new trade benefits” as a result of the TPP. Six of the other eleven countries in the pact already have trade deals with the United States, which means there are very few remaining barriers to be reduced. (One of the other five countries is Brunei, whose trade patterns will probably not cause China’s government to lose much sleep.)

If the pact was intended to hurt China, its designers did not do a very good job. It has lax rules of origins requirements. In some cases, for example most car parts, an item with as little as 35 percent value added from TPP countries could qualify for preferential treatment.

This means, for example, that car parts produced in China, with Vietnam adding 35 percent of the value (possibly in a Chinese owned firm) would get preferential treatment under the TPP. Since these requirements are difficult to enforce rigorously, it is likely that some items with as much as 70 percent value-added coming from China will get preferential treatment under the TPP. That does not sound like an effective way to exclude Chinese products. (NAFTA’s rules of origins for car parts required 62.5 percent of the value-added to come from the countries in the pact.)

The TPP also includes provisions that will make member countries pay more money for prescription drugs due to longer and stronger patent and related monopolies. It also includes provisions on e-commerce that would likely make it more difficult to crack down on the sorts of abuses we are now hearing about from Facebook. These features, which are major parts of the pact, are not likely to help the United States build an effective coalition against China on trade or anything else.

The piece also tells readers that Trump has:

“[…]shown a general reluctance to enter into multilateral trade deals because he believes these allow the United States to be ripped off.”

It is not clear how the Post knows what Trump “believes.” It can tell readers what he says, but given the frequency with which he reverses his positions, it seems unlikely he believes anything.

The Post asserted that:

“[…]entering into a new TPP could unify Trump with other trading partners and put new pressure on Beijing to either allow more imports into China or risk being alienated by other Asian countries, that would now received new trade benefits as part of the deal.”

Actually, the countries in the TPP will receive relatively few “new trade benefits” as a result of the TPP. Six of the other eleven countries in the pact already have trade deals with the United States, which means there are very few remaining barriers to be reduced. (One of the other five countries is Brunei, whose trade patterns will probably not cause China’s government to lose much sleep.)

If the pact was intended to hurt China, its designers did not do a very good job. It has lax rules of origins requirements. In some cases, for example most car parts, an item with as little as 35 percent value added from TPP countries could qualify for preferential treatment.

This means, for example, that car parts produced in China, with Vietnam adding 35 percent of the value (possibly in a Chinese owned firm) would get preferential treatment under the TPP. Since these requirements are difficult to enforce rigorously, it is likely that some items with as much as 70 percent value-added coming from China will get preferential treatment under the TPP. That does not sound like an effective way to exclude Chinese products. (NAFTA’s rules of origins for car parts required 62.5 percent of the value-added to come from the countries in the pact.)

The TPP also includes provisions that will make member countries pay more money for prescription drugs due to longer and stronger patent and related monopolies. It also includes provisions on e-commerce that would likely make it more difficult to crack down on the sorts of abuses we are now hearing about from Facebook. These features, which are major parts of the pact, are not likely to help the United States build an effective coalition against China on trade or anything else.

The piece also tells readers that Trump has:

“[…]shown a general reluctance to enter into multilateral trade deals because he believes these allow the United States to be ripped off.”

It is not clear how the Post knows what Trump “believes.” It can tell readers what he says, but given the frequency with which he reverses his positions, it seems unlikely he believes anything.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Once again Robert Samuelson takes a big swing and misses in his Washington Post column today. He argues that schools in states like West Virginia, Kentucky, and Oklahoma are underfunded and unable to pay their teachers a decent wage because of the cost for caring for the elderly.

This is wrong for two obvious reasons. First, these are all low-tax states. They could try something like raising taxes on higher income households. This is one way to get money.

The other problem is that a main reason why it costs so much to care for our elderly is that we pay our doctors and drug companies twice as much for their services and products as people in other wealthy countries. If we paid the same prices for our health care as people in Canada or Germany, it would free up more than $1 trillion annually for schools and other worthwhile items.

But The Washington Post doesn’t like to call attention to the incomes of the affluent, they would rather beat up on senior citizens.

Once again Robert Samuelson takes a big swing and misses in his Washington Post column today. He argues that schools in states like West Virginia, Kentucky, and Oklahoma are underfunded and unable to pay their teachers a decent wage because of the cost for caring for the elderly.

This is wrong for two obvious reasons. First, these are all low-tax states. They could try something like raising taxes on higher income households. This is one way to get money.

The other problem is that a main reason why it costs so much to care for our elderly is that we pay our doctors and drug companies twice as much for their services and products as people in other wealthy countries. If we paid the same prices for our health care as people in Canada or Germany, it would free up more than $1 trillion annually for schools and other worthwhile items.

But The Washington Post doesn’t like to call attention to the incomes of the affluent, they would rather beat up on senior citizens.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Many more of us are food consumers than farmers, yet somehow the prospect that a trade war with China will lead to lower prices for soybeans and other agricultural products is never reported as a positive development. Undoubtedly, the pain to farmers is much more important to them than the small benefit that many of us may see in the form of lower food prices, but reporters have felt it important to tell us about the small cost that many of us might see as a result of higher steel and aluminum prices as a result of Trump’s tariffs on these products.

This seems like a serious asymmetry in reporting on this topic.

Many more of us are food consumers than farmers, yet somehow the prospect that a trade war with China will lead to lower prices for soybeans and other agricultural products is never reported as a positive development. Undoubtedly, the pain to farmers is much more important to them than the small benefit that many of us may see in the form of lower food prices, but reporters have felt it important to tell us about the small cost that many of us might see as a result of higher steel and aluminum prices as a result of Trump’s tariffs on these products.

This seems like a serious asymmetry in reporting on this topic.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión