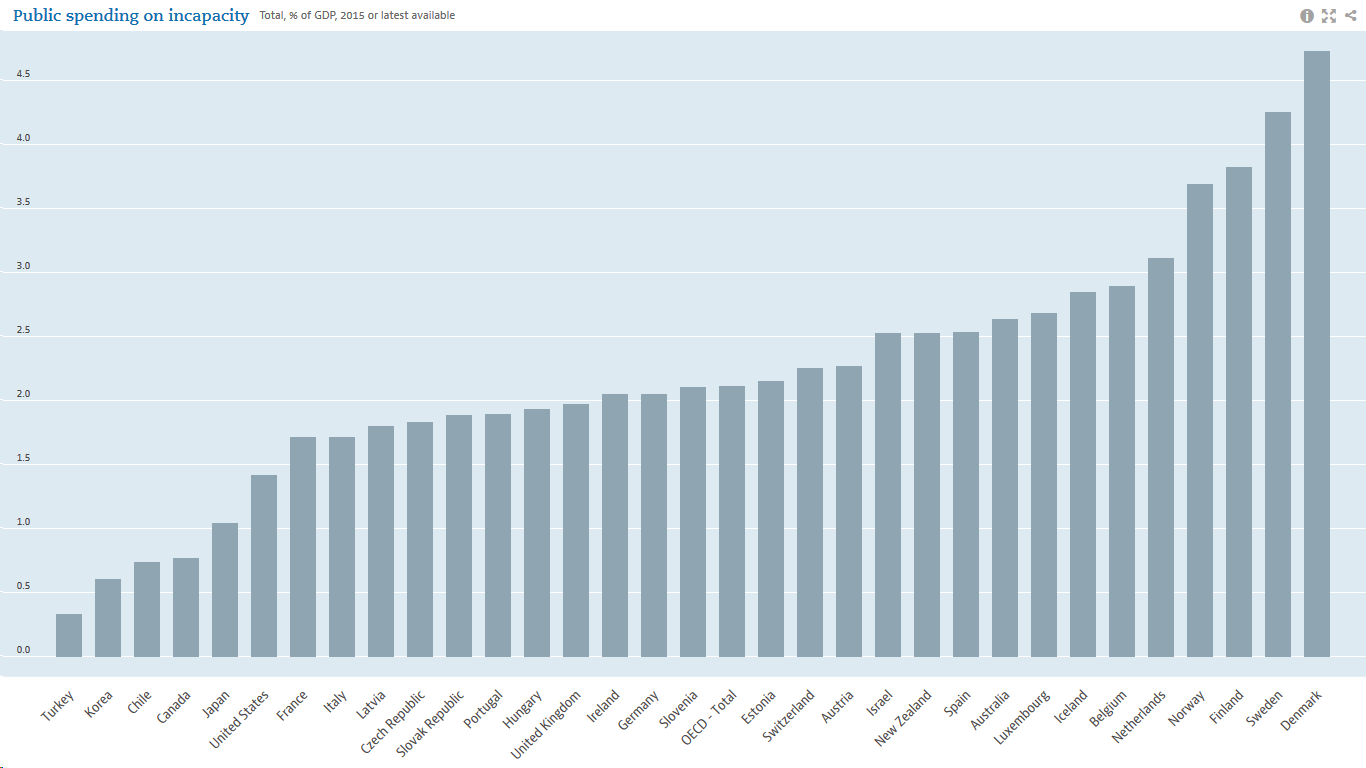

The paper owned by the man who got incredibly rich by avoiding state and local sales taxes is upset because workers are getting Social Security disability payments that average less than $1,300 a month. Since the US has one of the least generous disability programs of any wealthy country, this might seem like a strange concern. Here’s the picture from the OECD.

Source: OECD.

Of course the Post is also a paper that gets hysterical over the prospect that truck drivers will get pay increases. In short, these are folks who practice crude class war. They are okay with some crumbs for the poor, but anything that is good for ordinary workers means giving up money that could be in the pockets of the Bezoses of the world.

The paper owned by the man who got incredibly rich by avoiding state and local sales taxes is upset because workers are getting Social Security disability payments that average less than $1,300 a month. Since the US has one of the least generous disability programs of any wealthy country, this might seem like a strange concern. Here’s the picture from the OECD.

Source: OECD.

Of course the Post is also a paper that gets hysterical over the prospect that truck drivers will get pay increases. In short, these are folks who practice crude class war. They are okay with some crumbs for the poor, but anything that is good for ordinary workers means giving up money that could be in the pockets of the Bezoses of the world.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

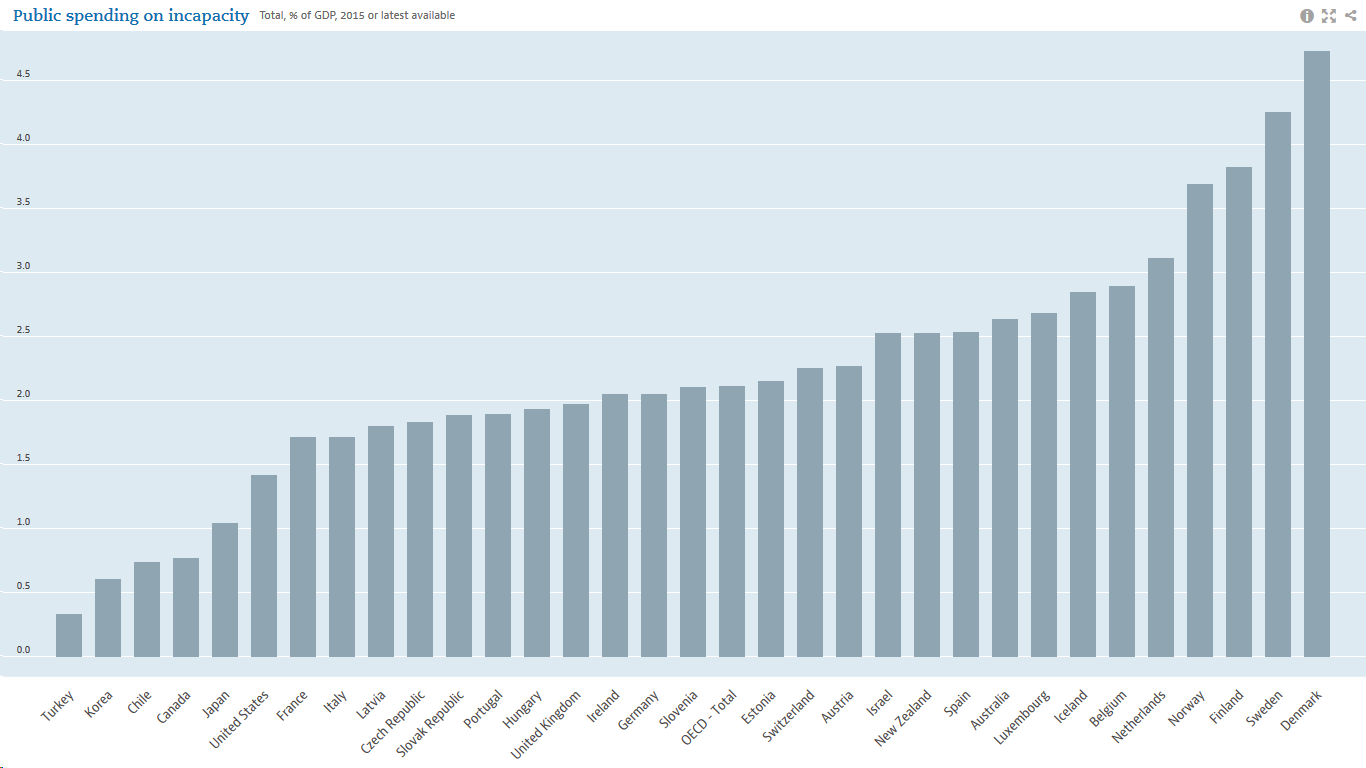

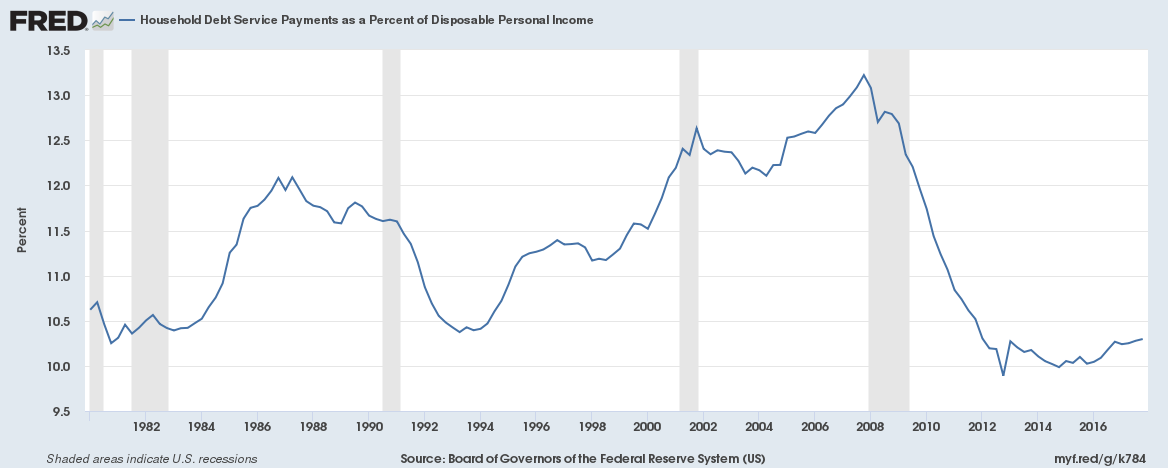

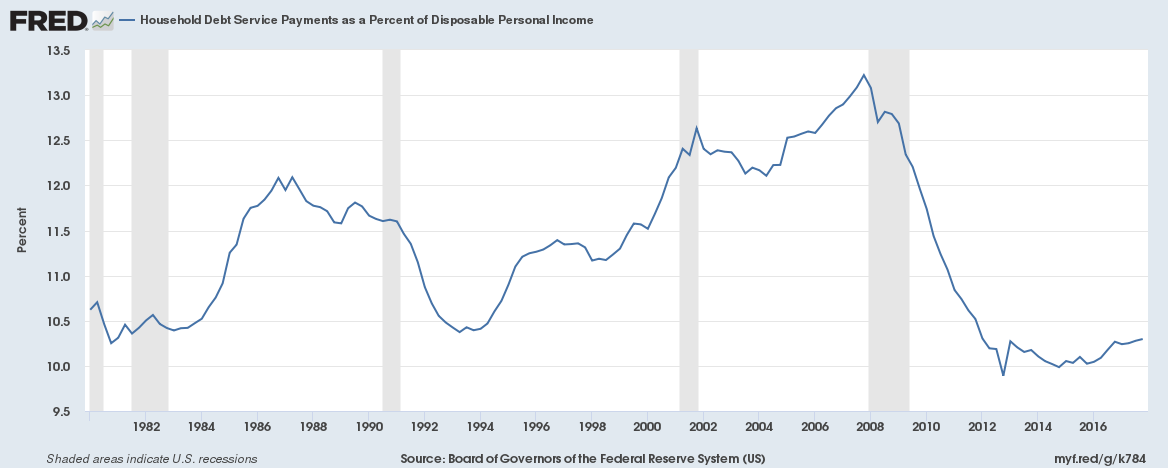

It is common practice for people who completely missed the housing bubble to warn about another impending debt crisis which will sink the economy when it bursts. In this vein, we have a New York Times editorial telling us about the dangerous increase in credit card debt.

The piece tells readers:

“And now rates are now rising at time when household debt reached a record $13.21 trillion in the first quarter. Household debt service payments as a percentage of disposable income hit 5.9 percent in the first quarter, according to the Federal Reserve, a figure not reached since just before the Great Recession. Average credit card debt per borrower is about $5,700 and growing at a rate of 4.7 percent while wages are growing at about 3 percent. That can’t continue forever.”

Since they had the Fed’s data on debt burdens in front of them, they should have known the full picture, which is below.

Are you scared?

The piece also includes several other silly comparisons, starting with the comparison of the growth in average household debt to the growth in the average hourly wage. The czar of apples-to-apples insists they use average household income, which in nominal terms is growing at roughly the same rate. The editorial also repeatedly compares wealth to the 2007 bubble peaks. Surprise! We haven’t recovered.

The basis of the piece is the bad news that when the Fed raises interest rates it will mean higher interest payments on credit card debt. I am happy to have the NYT as an ally in the battle against unnecessary interest rate hikes, but the burden on credit card debt hardly tops the charts as a reason. Suppose interest rates rise 2.0 percentage points (a huge increase) on $1 trillion in credit card debt. That comes to $20 billion a year or about $150 a year per household. That’s not altogether trivial, but not a concern that keeps me awake at night.

It would be a much greater concern if Fed rate hikes kept 2–3 million people from working and lowered the wages on 30 or 40 million low- and moderate-wage workers by reducing their bargaining power. There is some value in keeping your eye on the ball and actually knowing something about the topics on which you write.

It is common practice for people who completely missed the housing bubble to warn about another impending debt crisis which will sink the economy when it bursts. In this vein, we have a New York Times editorial telling us about the dangerous increase in credit card debt.

The piece tells readers:

“And now rates are now rising at time when household debt reached a record $13.21 trillion in the first quarter. Household debt service payments as a percentage of disposable income hit 5.9 percent in the first quarter, according to the Federal Reserve, a figure not reached since just before the Great Recession. Average credit card debt per borrower is about $5,700 and growing at a rate of 4.7 percent while wages are growing at about 3 percent. That can’t continue forever.”

Since they had the Fed’s data on debt burdens in front of them, they should have known the full picture, which is below.

Are you scared?

The piece also includes several other silly comparisons, starting with the comparison of the growth in average household debt to the growth in the average hourly wage. The czar of apples-to-apples insists they use average household income, which in nominal terms is growing at roughly the same rate. The editorial also repeatedly compares wealth to the 2007 bubble peaks. Surprise! We haven’t recovered.

The basis of the piece is the bad news that when the Fed raises interest rates it will mean higher interest payments on credit card debt. I am happy to have the NYT as an ally in the battle against unnecessary interest rate hikes, but the burden on credit card debt hardly tops the charts as a reason. Suppose interest rates rise 2.0 percentage points (a huge increase) on $1 trillion in credit card debt. That comes to $20 billion a year or about $150 a year per household. That’s not altogether trivial, but not a concern that keeps me awake at night.

It would be a much greater concern if Fed rate hikes kept 2–3 million people from working and lowered the wages on 30 or 40 million low- and moderate-wage workers by reducing their bargaining power. There is some value in keeping your eye on the ball and actually knowing something about the topics on which you write.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Bloomberg doesn’t seem quite as scared as the Washington Post, which worries that if truckers earn $60,000 a year it would sink the economy. But it also seems really disturbed that employers can’t get more drivers without paying them more. This one is, in some ways, even more over the top than the Post piece. It wants to blame the government.

The story here is that there are restrictions on hours, which used to be tracked using paper records but now are verified electronically. This makes cheating more difficult.

“Under the old regime, a driver making 40 cents a mile might drive 750 miles in 15 hours, averaging 50 miles an hour and making $300. His paperwork would claim 11 hours at 68 mph. Now, however, his time is electronically tracked and the 11-hour limit is strictly enforced. At 50 mph, he makes only $220.”

So, in the good old days, a driver putting in 15 hours a day pulled down $300, or $20 an hour. If we converted this into an hourly wage, with a 50 percent overtime premium after 8 hours, this comes to $16.21 an hour. In this story, the hourly pay actually rises somewhat to $22 an hour because of the evil regulations, but because the worker is putting in 27 percent fewer hours, her daily pay falls.

In any case, it is striking that no one seems to think that higher pay might be a good way to solve this shortage. I guess no one believes in market solutions at Bloomberg.

Bloomberg doesn’t seem quite as scared as the Washington Post, which worries that if truckers earn $60,000 a year it would sink the economy. But it also seems really disturbed that employers can’t get more drivers without paying them more. This one is, in some ways, even more over the top than the Post piece. It wants to blame the government.

The story here is that there are restrictions on hours, which used to be tracked using paper records but now are verified electronically. This makes cheating more difficult.

“Under the old regime, a driver making 40 cents a mile might drive 750 miles in 15 hours, averaging 50 miles an hour and making $300. His paperwork would claim 11 hours at 68 mph. Now, however, his time is electronically tracked and the 11-hour limit is strictly enforced. At 50 mph, he makes only $220.”

So, in the good old days, a driver putting in 15 hours a day pulled down $300, or $20 an hour. If we converted this into an hourly wage, with a 50 percent overtime premium after 8 hours, this comes to $16.21 an hour. In this story, the hourly pay actually rises somewhat to $22 an hour because of the evil regulations, but because the worker is putting in 27 percent fewer hours, her daily pay falls.

In any case, it is striking that no one seems to think that higher pay might be a good way to solve this shortage. I guess no one believes in market solutions at Bloomberg.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

You can make a very good living coming up with stories about how the US trade deficit is a good thing. After all, the jobs that are lost are overwhelming the jobs of less-educated workers. In addition, the fact that trade takes away the jobs of millions of less-educated workers puts downward pressure on the pay of people without college degrees more generally.

That means that the folks with college and advanced degrees, who are largely protected from international competition by protectionist measures (e.g. professional licensing requirements that exclude foreign-educated doctors, lawyers, dentists etc.) get to enjoy higher standards of living through two channels. First, they get to buy all those imported goodies (cars, television sets, clothes, etc.) at lower prices. Second, the help in areas like restaurant work, construction, landscaping etc. all get paid less, meaning lower prices for domestically produced goods. What’s not to like?

For this reason, it is hardly surprising to see David Frum’s piece in the Atlantic touting the wonders of the US trade deficit with China. Aren’t we lucky we have folks like Frum and magazines like The Atlantic to straighten out those stupid workers who can’t see how wonderful it is that they lose their jobs to import competition? I’m sure Frum and the Atlantic would have published the same lecture if we had free trade in physicians’, dentists’ and lawyers’ services and protection for manufactured goods, so that our trade deficit was due to payments to foreign professionals (working under contract, so the payment goes to their employer).

Anyhow, I have written endlessly on this topic. Given the amount of money to support dreck on the other side I can’t respond to all of it, but here are a couple of pieces for folks who may want a bit more background. It is also covered in the first chapter of my [free] book Rigged.

Note: “Frum” was misspelled in an earlier version.

You can make a very good living coming up with stories about how the US trade deficit is a good thing. After all, the jobs that are lost are overwhelming the jobs of less-educated workers. In addition, the fact that trade takes away the jobs of millions of less-educated workers puts downward pressure on the pay of people without college degrees more generally.

That means that the folks with college and advanced degrees, who are largely protected from international competition by protectionist measures (e.g. professional licensing requirements that exclude foreign-educated doctors, lawyers, dentists etc.) get to enjoy higher standards of living through two channels. First, they get to buy all those imported goodies (cars, television sets, clothes, etc.) at lower prices. Second, the help in areas like restaurant work, construction, landscaping etc. all get paid less, meaning lower prices for domestically produced goods. What’s not to like?

For this reason, it is hardly surprising to see David Frum’s piece in the Atlantic touting the wonders of the US trade deficit with China. Aren’t we lucky we have folks like Frum and magazines like The Atlantic to straighten out those stupid workers who can’t see how wonderful it is that they lose their jobs to import competition? I’m sure Frum and the Atlantic would have published the same lecture if we had free trade in physicians’, dentists’ and lawyers’ services and protection for manufactured goods, so that our trade deficit was due to payments to foreign professionals (working under contract, so the payment goes to their employer).

Anyhow, I have written endlessly on this topic. Given the amount of money to support dreck on the other side I can’t respond to all of it, but here are a couple of pieces for folks who may want a bit more background. It is also covered in the first chapter of my [free] book Rigged.

Note: “Frum” was misspelled in an earlier version.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an article featuring employers complaining that they couldn’t get low-cost immigrant labor. The piece focuses on the H-2B visa program which allows a limited number of foreign workers to come into the United States temporarily to work at low paying jobs such as restaurant work and housekeeping.

In particular, the article highlights the concerns of the two owners of landscaping businesses in the Denver area, Rhonda Fox, who owns a family business and Phil Steinhauer, who owns a larger business. Both complain that the limited number of foreign workers available under the visa program is hurting their business. They complain that, because of Denver’s low unemployment rate and highly educated workforce, they are unable to get workers at the $15 an hour pay rate they offer.

The piece explains:

“Landscape work is harsh. Digging in the dirt and heaving equipment in blistering heat produces aching backs and raw hands. Low-skilled workers can earn a similar wage making a sandwich or working in an air-conditioned warehouse.

“‘We put a $5,000 ad in The Denver Post, and we didn’t have one applicant,’ Ms. Fox said. Paying a wage high enough to attract local workers would put her out of business, she said, because her customers would balk at the resulting price increases.

“Like Ms. Fox and other landscapers, Mr. Steinhauer signed planting contracts with customers last year based on the assumption that his crews would earn roughly $15 an hour. ‘These are unskilled positions,’ he said. ‘Would you pay $50 to plant a bush in your garden?'”

Actually, some people would pay $50 to plant a bush in their garden, just as some people pay for chauffeurs, cooks, and nannies. The number of people who would hire such personal servants would obviously be much greater if we created a large supply of cheap foreign labor, but that would mean that the workers who currently hold these positions would earn much less money.

The NYT is apparently much more sympathetic to the relatively affluent employers who depend on cheap labor than the workers who would get less pay as a result of the competition. Unfortunately, its concern does not extend to those of us who have to go to doctors and dentists who must pay much higher prices for their services, because the government rigidly restricts the competition for these very highly paid workers.

The NYT had an article featuring employers complaining that they couldn’t get low-cost immigrant labor. The piece focuses on the H-2B visa program which allows a limited number of foreign workers to come into the United States temporarily to work at low paying jobs such as restaurant work and housekeeping.

In particular, the article highlights the concerns of the two owners of landscaping businesses in the Denver area, Rhonda Fox, who owns a family business and Phil Steinhauer, who owns a larger business. Both complain that the limited number of foreign workers available under the visa program is hurting their business. They complain that, because of Denver’s low unemployment rate and highly educated workforce, they are unable to get workers at the $15 an hour pay rate they offer.

The piece explains:

“Landscape work is harsh. Digging in the dirt and heaving equipment in blistering heat produces aching backs and raw hands. Low-skilled workers can earn a similar wage making a sandwich or working in an air-conditioned warehouse.

“‘We put a $5,000 ad in The Denver Post, and we didn’t have one applicant,’ Ms. Fox said. Paying a wage high enough to attract local workers would put her out of business, she said, because her customers would balk at the resulting price increases.

“Like Ms. Fox and other landscapers, Mr. Steinhauer signed planting contracts with customers last year based on the assumption that his crews would earn roughly $15 an hour. ‘These are unskilled positions,’ he said. ‘Would you pay $50 to plant a bush in your garden?'”

Actually, some people would pay $50 to plant a bush in their garden, just as some people pay for chauffeurs, cooks, and nannies. The number of people who would hire such personal servants would obviously be much greater if we created a large supply of cheap foreign labor, but that would mean that the workers who currently hold these positions would earn much less money.

The NYT is apparently much more sympathetic to the relatively affluent employers who depend on cheap labor than the workers who would get less pay as a result of the competition. Unfortunately, its concern does not extend to those of us who have to go to doctors and dentists who must pay much higher prices for their services, because the government rigidly restricts the competition for these very highly paid workers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

No one expects great insights from people who write columns for the Washington Post but Dana Milbank hit a serious low today when he referred to the fact that Representative Joseph Crowley took large amounts of money from the financial industry and other special interests as “largely non-ideological.” Those of us who don’t write columns for the Washington Post realize that campaign contributors are not in the charity business. They expect and generally get something in exchange for their money.

At the very least, they do not give money to people who they expect to push efforts to seriously harm their profits (which Dodd-Frank did not do) or to have them jailed when they break the law. They apparently felt confident that Crowley could be relied upon in these areas.

No one expects great insights from people who write columns for the Washington Post but Dana Milbank hit a serious low today when he referred to the fact that Representative Joseph Crowley took large amounts of money from the financial industry and other special interests as “largely non-ideological.” Those of us who don’t write columns for the Washington Post realize that campaign contributors are not in the charity business. They expect and generally get something in exchange for their money.

At the very least, they do not give money to people who they expect to push efforts to seriously harm their profits (which Dodd-Frank did not do) or to have them jailed when they break the law. They apparently felt confident that Crowley could be relied upon in these areas.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

For folks who can remember all the way back to last fall, the promise was that a huge boom in investment would lead to more rapid productivity growth. Higher productivity would mean pay would be close to 10 percent higher than in the baseline scenario after a decade.

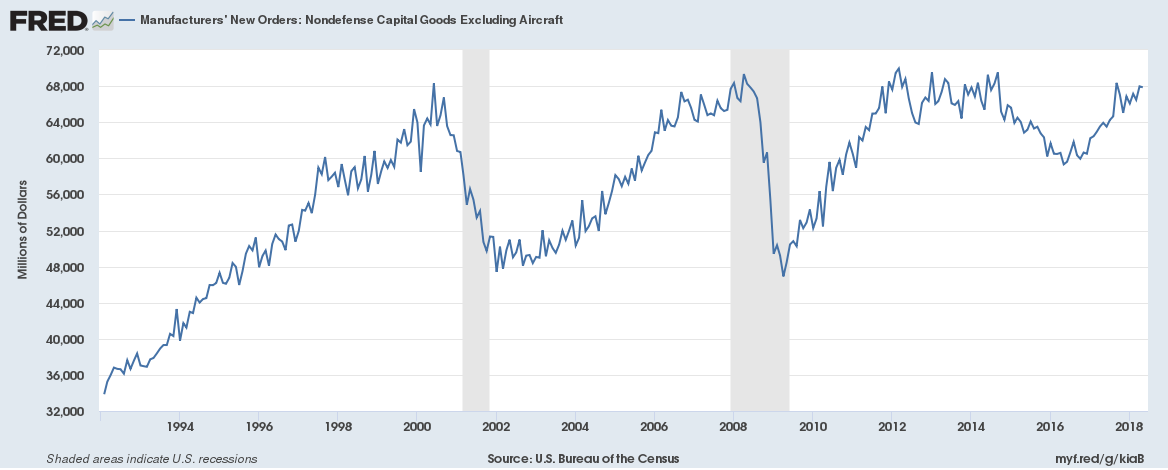

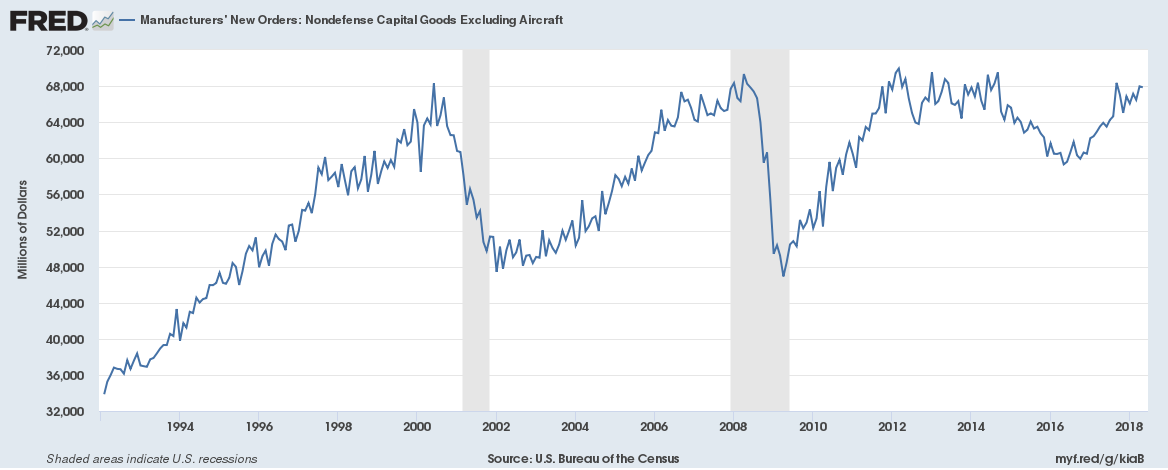

Well, the data disagree. We got new data on capital goods orders yesterday. Here’s the picture.

If you see a boom here since the tax cut, you may want to get the prescription on your glasses checked. It’s not a terrible story, but we’re still below the pre-recession peaks and even the levels reached during the horrible Obama years. Oh well, at least rich people got lots of money out of the deal.

By the way, the drop in capital goods orders in 2015 and 2016 was due to the plunge in world oil prices from $100 a barrel to $40 a barrel. Much of the increase in the last year and a half has been attributable to the partial recovery to $70 a barrel. I am not inclined to give the Trump administration the blame for higher gas prices, but I suppose if they insist, we can yell at them over $3 per gallon gas.

For folks who can remember all the way back to last fall, the promise was that a huge boom in investment would lead to more rapid productivity growth. Higher productivity would mean pay would be close to 10 percent higher than in the baseline scenario after a decade.

Well, the data disagree. We got new data on capital goods orders yesterday. Here’s the picture.

If you see a boom here since the tax cut, you may want to get the prescription on your glasses checked. It’s not a terrible story, but we’re still below the pre-recession peaks and even the levels reached during the horrible Obama years. Oh well, at least rich people got lots of money out of the deal.

By the way, the drop in capital goods orders in 2015 and 2016 was due to the plunge in world oil prices from $100 a barrel to $40 a barrel. Much of the increase in the last year and a half has been attributable to the partial recovery to $70 a barrel. I am not inclined to give the Trump administration the blame for higher gas prices, but I suppose if they insist, we can yell at them over $3 per gallon gas.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Mexico seems all but certain to elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a left-wing candidate, as president this weekend. One of the main factors is the contempt with which the Mexican public regards a political and economic elite that have run the country in a way that has produced few benefits for the bulk of the population. It is striking that this uprising is taking place almost a quarter century into the NAFTA era.

We were told endlessly by our elites that NAFTA was doing great things for Mexico. The Washington Post stands out as a particular villain in this story. It repeatedly ran fantasy pieces on how NAFTA was creating a thriving middle class in Mexico.

The Post even went full Trump back in 2007 when it made up the absurd claim that NAFTA had led Mexico’s economy to quadruple between 1998 and 2007. The actual figure was 84.2 percent. Unfortunately, the Washington Post has not been the only institution to make up numbers to promote NAFTA. The World Bank got into the act too.

A true assessment of the impact of NAFTA on Mexico would require considerable research, but just at the basic level of GDP growth it has been a disaster. Mexico’s per capita GDP has risen at just a 1.2 percent annual rate since 1993. This compares to a 1.5 percent annual rate in the United States. This means that the countries are even further apart economically today than when the agreement took effect in 1994, but don’t hold your breath waiting for the NAFTA proponents to acknowledge that it might not have been a good deal.

Mexico seems all but certain to elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a left-wing candidate, as president this weekend. One of the main factors is the contempt with which the Mexican public regards a political and economic elite that have run the country in a way that has produced few benefits for the bulk of the population. It is striking that this uprising is taking place almost a quarter century into the NAFTA era.

We were told endlessly by our elites that NAFTA was doing great things for Mexico. The Washington Post stands out as a particular villain in this story. It repeatedly ran fantasy pieces on how NAFTA was creating a thriving middle class in Mexico.

The Post even went full Trump back in 2007 when it made up the absurd claim that NAFTA had led Mexico’s economy to quadruple between 1998 and 2007. The actual figure was 84.2 percent. Unfortunately, the Washington Post has not been the only institution to make up numbers to promote NAFTA. The World Bank got into the act too.

A true assessment of the impact of NAFTA on Mexico would require considerable research, but just at the basic level of GDP growth it has been a disaster. Mexico’s per capita GDP has risen at just a 1.2 percent annual rate since 1993. This compares to a 1.5 percent annual rate in the United States. This means that the countries are even further apart economically today than when the agreement took effect in 1994, but don’t hold your breath waiting for the NAFTA proponents to acknowledge that it might not have been a good deal.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had yet another hysterical piece about how “America’s Severe Trucker Shortage” could undermine the economy. While the piece features the usual complaints from employers about how they can’t get anyone to work for them no matter how much they pay, the data indicate they aren’t trying very hard. Here’s the inflation adjusted average hourly pay for production and non-supervisory workers in the trucking industry since 1990.

Real Hourly Wage: Truck Transportation, Production and Non-Supervisory Workers

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As the figure shows, the real hourly wage for workers in the industry is still more than 10 percent below its 1990 peak. While this would include some workers who are not truckers (for example, the people handling orders), truckers would be the bulk of employees and certainly, if their pay was rising rapidly it would show up in the data.

The piece includes this incredible assertion: “economists say, if competition for truckers pushes up prices so quickly that the country faces uncontrolled inflation, which can easily lead to a recession,” although it doesn’t actually name any economists who say anything like this. There are a bit less than 1.3 million production and non-supervisory workers in the trucking industry. Suppose their pay went up by an average of $20,000 a year, which would be more than a 40 percent increase. (The Bureau of Labor Statistics puts their average pay currently at just $46,000 a year.)

This huge pay increase would then add $20 billion to costs in the economy, or roughly 0.1 percent of GDP. (It’s a bit less than 10 percent of what we pay our doctors each year.) It would be very interesting to see if the Post could find any economist who would say that this would lead to “uncontrolled inflation.”

The Washington Post had yet another hysterical piece about how “America’s Severe Trucker Shortage” could undermine the economy. While the piece features the usual complaints from employers about how they can’t get anyone to work for them no matter how much they pay, the data indicate they aren’t trying very hard. Here’s the inflation adjusted average hourly pay for production and non-supervisory workers in the trucking industry since 1990.

Real Hourly Wage: Truck Transportation, Production and Non-Supervisory Workers

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As the figure shows, the real hourly wage for workers in the industry is still more than 10 percent below its 1990 peak. While this would include some workers who are not truckers (for example, the people handling orders), truckers would be the bulk of employees and certainly, if their pay was rising rapidly it would show up in the data.

The piece includes this incredible assertion: “economists say, if competition for truckers pushes up prices so quickly that the country faces uncontrolled inflation, which can easily lead to a recession,” although it doesn’t actually name any economists who say anything like this. There are a bit less than 1.3 million production and non-supervisory workers in the trucking industry. Suppose their pay went up by an average of $20,000 a year, which would be more than a 40 percent increase. (The Bureau of Labor Statistics puts their average pay currently at just $46,000 a year.)

This huge pay increase would then add $20 billion to costs in the economy, or roughly 0.1 percent of GDP. (It’s a bit less than 10 percent of what we pay our doctors each year.) It would be very interesting to see if the Post could find any economist who would say that this would lead to “uncontrolled inflation.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In a period of record low productivity growth Thomas Friedman tells us the robots are taking all the jobs. Hey, no one ever said you had to have a clue to write for the New York Times. Here’s the punch line:

“From 1960 to 2000, Quartz reported, U.S. manufacturing employment stayed roughly steady at around 17.5 million jobs. But between 2000 and 2010, thanks largely to digitization and automation, ‘manufacturing employment plummeted by more than a third,’ which was ‘worse than any decade in U.S. manufacturing history.'”

The little secret that Friedman apparently has not heard about is the explosion of the trade deficit, which peaked at almost 6 percent of GDP ($1.2 trillion in today’s economy) in 2005 and 2006. This matters, because the reason millions of manufacturing workers lost their jobs in this period was decisions on trade policy by leaders of both political parties, not anything the robots did. That changes the story of the collapse of political parties (the theme of Friedman’s piece) a bit.

Friedman’s confusion continues in the next paragraph:

“These climate changes are reshaping the ecosystem of work — wiping out huge numbers of middle-skilled jobs — and this is reshaping the ecosystem of learning, making lifelong learning the new baseline for advancement.

“These three climate changes are also reshaping geopolitics. They are like a hurricane that is blowing apart weak nations that were O.K. in the Cold War — when superpowers would shower them with foreign aid and arms, when China could not compete with them for low-skilled work and when climate change, deforestation and population explosions had not wiped out vast amounts of their small-scale agriculture.”

The reason that highly skilled workers are benefiting at the expense of less-educated workers is because we have made patent and copyright protection longer and stronger. It is more than a little bizarre that ostensibly educated people have such a hard time understanding this.

We have these protections to provide incentives for people to innovate and do creative work. That is explicit policy. Then we are worried that people who innovate and do creative work are getting too much money at the expense of everyone else. Hmmm, any ideas here?

Remember, without patents and copyrights, Bill Gates would still be working for a living.

One more item, China competes with “low-skilled” work in the United States and not with doctors and dentists because our laws block the latter form of competition. There was nothing natural about this one either. Yes, this is all in my [free] book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.

In a period of record low productivity growth Thomas Friedman tells us the robots are taking all the jobs. Hey, no one ever said you had to have a clue to write for the New York Times. Here’s the punch line:

“From 1960 to 2000, Quartz reported, U.S. manufacturing employment stayed roughly steady at around 17.5 million jobs. But between 2000 and 2010, thanks largely to digitization and automation, ‘manufacturing employment plummeted by more than a third,’ which was ‘worse than any decade in U.S. manufacturing history.'”

The little secret that Friedman apparently has not heard about is the explosion of the trade deficit, which peaked at almost 6 percent of GDP ($1.2 trillion in today’s economy) in 2005 and 2006. This matters, because the reason millions of manufacturing workers lost their jobs in this period was decisions on trade policy by leaders of both political parties, not anything the robots did. That changes the story of the collapse of political parties (the theme of Friedman’s piece) a bit.

Friedman’s confusion continues in the next paragraph:

“These climate changes are reshaping the ecosystem of work — wiping out huge numbers of middle-skilled jobs — and this is reshaping the ecosystem of learning, making lifelong learning the new baseline for advancement.

“These three climate changes are also reshaping geopolitics. They are like a hurricane that is blowing apart weak nations that were O.K. in the Cold War — when superpowers would shower them with foreign aid and arms, when China could not compete with them for low-skilled work and when climate change, deforestation and population explosions had not wiped out vast amounts of their small-scale agriculture.”

The reason that highly skilled workers are benefiting at the expense of less-educated workers is because we have made patent and copyright protection longer and stronger. It is more than a little bizarre that ostensibly educated people have such a hard time understanding this.

We have these protections to provide incentives for people to innovate and do creative work. That is explicit policy. Then we are worried that people who innovate and do creative work are getting too much money at the expense of everyone else. Hmmm, any ideas here?

Remember, without patents and copyrights, Bill Gates would still be working for a living.

One more item, China competes with “low-skilled” work in the United States and not with doctors and dentists because our laws block the latter form of competition. There was nothing natural about this one either. Yes, this is all in my [free] book Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión