No one wants to pay higher taxes, but we all understand the need when there is a good cause. Therefore, consumers shouldn’t have any issues paying an extra $20 billion a year ($200 billion over a 10-year budget horizon) to force China to pay Boeing, Pfizer, Microsoft and other major US corporations more money for their patent and copyright monopolies.

This is explicitly the story, as the Post reports:

“Administration officials said the tariff fight is aimed at forcing China to stop stealing American intellectual property and to abandon policies that effectively force U.S. companies to surrender their trade secrets in return for access to the Chinese market.

“‘These practices are an existential threat to America’s most critical comparative advantage and the future of our economy,’ said Robert E. Lighthizer, the president’s chief trade negotiator.”

Of course, the cost to US consumers is likely to be far more than $20 billion a year if the Trump administration wins its trade war, since it will mean that the prices of goods and services we import from China will be higher because they have to pay more money to US corporations for these intellectual property claims.

However, this will create some good-paying jobs. There will be more demand for economists doing research on the causes of inequality.

Addendum:

In a rush, I followed standard media practice instead of good reporting. The proposed $20 billion in tariffs comes to roughly $150 per family per year.

No one wants to pay higher taxes, but we all understand the need when there is a good cause. Therefore, consumers shouldn’t have any issues paying an extra $20 billion a year ($200 billion over a 10-year budget horizon) to force China to pay Boeing, Pfizer, Microsoft and other major US corporations more money for their patent and copyright monopolies.

This is explicitly the story, as the Post reports:

“Administration officials said the tariff fight is aimed at forcing China to stop stealing American intellectual property and to abandon policies that effectively force U.S. companies to surrender their trade secrets in return for access to the Chinese market.

“‘These practices are an existential threat to America’s most critical comparative advantage and the future of our economy,’ said Robert E. Lighthizer, the president’s chief trade negotiator.”

Of course, the cost to US consumers is likely to be far more than $20 billion a year if the Trump administration wins its trade war, since it will mean that the prices of goods and services we import from China will be higher because they have to pay more money to US corporations for these intellectual property claims.

However, this will create some good-paying jobs. There will be more demand for economists doing research on the causes of inequality.

Addendum:

In a rush, I followed standard media practice instead of good reporting. The proposed $20 billion in tariffs comes to roughly $150 per family per year.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s the implication of this piece warning that a tight labor might force companies to raise wages and this could be hard on many companies’ profits. We know that profit shares are near record highs, especially after the Trump tax cut substantially reduced companies’ tax liabilities.

This means that the vast majority of companies should be able to easily absorb higher wages without passing the cost on in prices. Undoubtedly some companies are not well-situated because they are less efficient or face weak demand for their products. These companies may go out of business.

This is what happens in capitalism. It is how productivity increases and living standards improve through time. Inefficient companies shrink and go out of business, while more dynamic companies grow and prosper.

The piece also bizarrely highlights the 2.7 percent increase in workers’ pay over the last year as though it is a big bonanza. This is just equal to the rate of inflation over this period, so in effect, the WSJ is upset that in an economy with 4.0 percent unemployment workers have enough bargaining power to keep even with inflation.

That’s the implication of this piece warning that a tight labor might force companies to raise wages and this could be hard on many companies’ profits. We know that profit shares are near record highs, especially after the Trump tax cut substantially reduced companies’ tax liabilities.

This means that the vast majority of companies should be able to easily absorb higher wages without passing the cost on in prices. Undoubtedly some companies are not well-situated because they are less efficient or face weak demand for their products. These companies may go out of business.

This is what happens in capitalism. It is how productivity increases and living standards improve through time. Inefficient companies shrink and go out of business, while more dynamic companies grow and prosper.

The piece also bizarrely highlights the 2.7 percent increase in workers’ pay over the last year as though it is a big bonanza. This is just equal to the rate of inflation over this period, so in effect, the WSJ is upset that in an economy with 4.0 percent unemployment workers have enough bargaining power to keep even with inflation.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I sometimes go under the professional name of “No One” as in “no one saw the financial crisis coming.” I apparently need to use this identification again when it comes to a trade war with China.

On Morning Edition today, Jeff Greene interviewed Jonah Goldberg, senior editor at National Review. Mr. Goldberg told Greene how conservatives are free traders so they generally are opposed to Trump’s tariffs. He then suggested that a way out for Trump would be to focus on China’s intellectual property “theft,” since everybody agrees this is a problem.

This is where I come in. I don’t particularly consider the fact that China doesn’t pay Microsoft, Pfizer, and Boeing what they think they are owed to be a problem for people who are not major stockholders in these companies. As a basic proposition, the more money China sends to these companies, the larger its trade surplus in other areas.

More generally, as a basic proposition, it is more than a bit bizarre that so many economists can somehow believe both that without patent and copyright monopolies and related protections, there would be no incentive for innovation and that technology causes inequality. If we have a problem with inequality due to “technology,” it is due to the way in which we assign property rights. Shorter and weaker patents and copyrights mean less money to the people on top and more money for everyone else.

That seems pretty simple, but recognizing an $8 trillion housing bubble ($12 trillion relative to today’s economy) also seemed pretty simple. There is a reason people say that economists are not very good at economics.

I sometimes go under the professional name of “No One” as in “no one saw the financial crisis coming.” I apparently need to use this identification again when it comes to a trade war with China.

On Morning Edition today, Jeff Greene interviewed Jonah Goldberg, senior editor at National Review. Mr. Goldberg told Greene how conservatives are free traders so they generally are opposed to Trump’s tariffs. He then suggested that a way out for Trump would be to focus on China’s intellectual property “theft,” since everybody agrees this is a problem.

This is where I come in. I don’t particularly consider the fact that China doesn’t pay Microsoft, Pfizer, and Boeing what they think they are owed to be a problem for people who are not major stockholders in these companies. As a basic proposition, the more money China sends to these companies, the larger its trade surplus in other areas.

More generally, as a basic proposition, it is more than a bit bizarre that so many economists can somehow believe both that without patent and copyright monopolies and related protections, there would be no incentive for innovation and that technology causes inequality. If we have a problem with inequality due to “technology,” it is due to the way in which we assign property rights. Shorter and weaker patents and copyrights mean less money to the people on top and more money for everyone else.

That seems pretty simple, but recognizing an $8 trillion housing bubble ($12 trillion relative to today’s economy) also seemed pretty simple. There is a reason people say that economists are not very good at economics.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s not clear how the paper made these determinations, but it does assert them to be true in the second paragraph of an article on the Trump administration’s plans to reduce the rights of federal employees:

“The administration describes Trump’s new rules, issued in May, as an effort to streamline a bloated bureaucracy and improve accountability within the federal workforce of 2.1 million.”

While it is certainly possible that the Trump administration is motivated by a desire to make government more efficient, given its willingness to grant no-bid contracts to politically connected companies, government efficiency does not seem to be a priority for the Trump administration. A plausible alternative that the Post seems to rule out with this assertion is that Trump is attacking a group of workers that he sees as political enemies.

It’s not clear how the paper made these determinations, but it does assert them to be true in the second paragraph of an article on the Trump administration’s plans to reduce the rights of federal employees:

“The administration describes Trump’s new rules, issued in May, as an effort to streamline a bloated bureaucracy and improve accountability within the federal workforce of 2.1 million.”

While it is certainly possible that the Trump administration is motivated by a desire to make government more efficient, given its willingness to grant no-bid contracts to politically connected companies, government efficiency does not seem to be a priority for the Trump administration. A plausible alternative that the Post seems to rule out with this assertion is that Trump is attacking a group of workers that he sees as political enemies.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Any newspaper can hire reporters, but The New York Times hires mind readers. Yes, they are at it again. In an article on Trump’s demand that other NATO countries increase their military spending to 2.0 percent of GDP the NYT tells readers;

“Mr. Trump, who appears to have a special animus toward Germany, believes that Berlin has developed a vibrant social system and thriving export-driven economy unfairly and on the back of the United States, by not spending enough on defense.”

It’s so great that we have the NYT to tell us that Trump really has such incredibly absurd beliefs. The idea that Germany’s economy would somehow have suffered horribly if it had spent an additional 1.0 percent of GDP on the military is pretty crazy, especially since it has suffered from a serious lack of demand for the last decade.

This doesn’t mean that military spending would be the best use of Germany’s resources. But it’s very hard to make a case that additional spending, even if it were entirely wasteful from a social and economic standpoint, would have devastated Germany’s economy. In fact, it probably would have led to somewhat stronger growth and surely would have benefitted the other EU countries that are Germany’s largest trading partners.

Any newspaper can hire reporters, but The New York Times hires mind readers. Yes, they are at it again. In an article on Trump’s demand that other NATO countries increase their military spending to 2.0 percent of GDP the NYT tells readers;

“Mr. Trump, who appears to have a special animus toward Germany, believes that Berlin has developed a vibrant social system and thriving export-driven economy unfairly and on the back of the United States, by not spending enough on defense.”

It’s so great that we have the NYT to tell us that Trump really has such incredibly absurd beliefs. The idea that Germany’s economy would somehow have suffered horribly if it had spent an additional 1.0 percent of GDP on the military is pretty crazy, especially since it has suffered from a serious lack of demand for the last decade.

This doesn’t mean that military spending would be the best use of Germany’s resources. But it’s very hard to make a case that additional spending, even if it were entirely wasteful from a social and economic standpoint, would have devastated Germany’s economy. In fact, it probably would have led to somewhat stronger growth and surely would have benefitted the other EU countries that are Germany’s largest trading partners.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The second fact appeared in a NYT article reporting on how nursing homes are frequently understaffed; the first did not. As many doctors angrily told me after reading a column I did on the protections that inflate doctors’ pay, nursing assistants save lives.

Yes, we pay lots of money for health care in this country, more than twice as much as the average for other wealthy countries. Unfortunately, we don’t have better outcomes to justify this spending. A big part of this story is how much we pay our doctors and how little we pay less politically powerful workers in the health care industry. (Yes, inflated drug and medical equipment prices and a cesspool insurance industry are also big parts of the story, all discussed in Rigged [it’s free].)

The second fact appeared in a NYT article reporting on how nursing homes are frequently understaffed; the first did not. As many doctors angrily told me after reading a column I did on the protections that inflate doctors’ pay, nursing assistants save lives.

Yes, we pay lots of money for health care in this country, more than twice as much as the average for other wealthy countries. Unfortunately, we don’t have better outcomes to justify this spending. A big part of this story is how much we pay our doctors and how little we pay less politically powerful workers in the health care industry. (Yes, inflated drug and medical equipment prices and a cesspool insurance industry are also big parts of the story, all discussed in Rigged [it’s free].)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The top of the hour lead into Morning Edition (sorry, no link) told listeners that hiring will be down for June because employers can’t find workers. Of course, employers who understand basic economics can find workers: they just raise pay to pull them away from competitors.

We aren’t seeing any large-scale increases in pay despite near-record profit shares. This suggests that either employers really are not short of workers or that they are too incompetent to understand the basics of the market.

The top of the hour lead into Morning Edition (sorry, no link) told listeners that hiring will be down for June because employers can’t find workers. Of course, employers who understand basic economics can find workers: they just raise pay to pull them away from competitors.

We aren’t seeing any large-scale increases in pay despite near-record profit shares. This suggests that either employers really are not short of workers or that they are too incompetent to understand the basics of the market.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Like the Supreme Court, the Fed has considerable independence from day-to-day politics. It has seven governors who are appointed by the president and approved by the Senate. They can serve 14 year terms, although most do not stay for the full period.

The Open Market Committee that sets interest rate policy also includes the twelve district bank presidents. Five of these twelve bank presidents have a vote at any point in time, although all twelve take part in the discussion. The bank presidents are appointed through a somewhat opaque process that has historically been dominated by the financial industry, although this process was opened up somewhat during Janet Yellen’s tenure as Fed chair.

This process insulates the Fed from the whims of the president and other political figures. However, there is nothing inappropriate about the president or any other elected official commenting on Fed policy, as The New York Times implies in this piece.

Given the close ties of the bank presidents, and often the governors, to the financial industry, a Fed that is considered off limits for political debate is likely to be overly responsive to the concerns of the financial industry. This is likely to mean, for example, excessive concern over inflation and inadequate attention to the full employment part of the Fed’s mandate. It is understandable that the financial industry would like to keep the public unaware of the importance of the Fed’s actions, but the public as a whole does not share this interest.

Like the Supreme Court, the Fed has considerable independence from day-to-day politics. It has seven governors who are appointed by the president and approved by the Senate. They can serve 14 year terms, although most do not stay for the full period.

The Open Market Committee that sets interest rate policy also includes the twelve district bank presidents. Five of these twelve bank presidents have a vote at any point in time, although all twelve take part in the discussion. The bank presidents are appointed through a somewhat opaque process that has historically been dominated by the financial industry, although this process was opened up somewhat during Janet Yellen’s tenure as Fed chair.

This process insulates the Fed from the whims of the president and other political figures. However, there is nothing inappropriate about the president or any other elected official commenting on Fed policy, as The New York Times implies in this piece.

Given the close ties of the bank presidents, and often the governors, to the financial industry, a Fed that is considered off limits for political debate is likely to be overly responsive to the concerns of the financial industry. This is likely to mean, for example, excessive concern over inflation and inadequate attention to the full employment part of the Fed’s mandate. It is understandable that the financial industry would like to keep the public unaware of the importance of the Fed’s actions, but the public as a whole does not share this interest.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

With Donald Trump’s trade war with China heating up I thought I should bring in Mr. Arithmetic to clarify the situation. Trump apparently thinks that he holds all the cards in this one because the US imports much more than it exports to China.

As I pointed out previously, China has other weapons. For example, it can just stop respecting US patents and copyrights altogether, sending items all over the world that don’t include any royalty payments or licensing fees. This could reduce the price of patented drugs by 90 percent or more and make all of Microsoft’s software free.

But even ignoring the other weapons that China has in a trade war, the idea that the country can’t get by without the US market doesn’t fit the data. At the most basic level, China exported a bit more than $500 billion in goods and services to the United States last year. This comes to a bit more than 4.0 percent of its GDP, measured on a dollar exchange rate basis.

As many analysts have noted, much of the value of these exports is not actually valued-added in China. For example, the full value of an iPhone produced in China will be counted as an export to the United States even though most of the value comes from software developed in the United States and parts imported from other countries. Perhaps 40 percent or more of the trade deficit reflects value-added from other countries. (On the flip side, many of the imports from other countries include value-added from Chinese products.)

But let’s ignore this issue. Suppose Donald Trump’s get-tough trade policies reduce our imports from China by 50 percent, a huge reduction. This would come to roughly 2.0 percent of China’s GDP. Will this have China screaming “uncle?”

Probably not. As Mr. Arithmetic points out, China’s trade surplus fell by 4.4 percentage points of GDP from 2008 to 2009, yet its economy still grew by more than 9.0 percent that year and by more than 10.0 percent the next year. While all of China’s annual data should be viewed with some skepticism, few doubt the basic story. China managed to get through the recession without a major hit to its growth.

Of course, that drop in exports was due to an unexpected economic crisis, this one would be due to a politically motivated trade war. Mr. Arithmetic does not expect China to be giving in any time soon.

With Donald Trump’s trade war with China heating up I thought I should bring in Mr. Arithmetic to clarify the situation. Trump apparently thinks that he holds all the cards in this one because the US imports much more than it exports to China.

As I pointed out previously, China has other weapons. For example, it can just stop respecting US patents and copyrights altogether, sending items all over the world that don’t include any royalty payments or licensing fees. This could reduce the price of patented drugs by 90 percent or more and make all of Microsoft’s software free.

But even ignoring the other weapons that China has in a trade war, the idea that the country can’t get by without the US market doesn’t fit the data. At the most basic level, China exported a bit more than $500 billion in goods and services to the United States last year. This comes to a bit more than 4.0 percent of its GDP, measured on a dollar exchange rate basis.

As many analysts have noted, much of the value of these exports is not actually valued-added in China. For example, the full value of an iPhone produced in China will be counted as an export to the United States even though most of the value comes from software developed in the United States and parts imported from other countries. Perhaps 40 percent or more of the trade deficit reflects value-added from other countries. (On the flip side, many of the imports from other countries include value-added from Chinese products.)

But let’s ignore this issue. Suppose Donald Trump’s get-tough trade policies reduce our imports from China by 50 percent, a huge reduction. This would come to roughly 2.0 percent of China’s GDP. Will this have China screaming “uncle?”

Probably not. As Mr. Arithmetic points out, China’s trade surplus fell by 4.4 percentage points of GDP from 2008 to 2009, yet its economy still grew by more than 9.0 percent that year and by more than 10.0 percent the next year. While all of China’s annual data should be viewed with some skepticism, few doubt the basic story. China managed to get through the recession without a major hit to its growth.

Of course, that drop in exports was due to an unexpected economic crisis, this one would be due to a politically motivated trade war. Mr. Arithmetic does not expect China to be giving in any time soon.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s the implication of this CNBC piece that claims that hiring is down because businesses can’t find qualified workers. If this is really the problem, then the solution, as everyone learns in intro economics, is to raise wages. For some reason, CEOs apparently can’t seem to figure this one out, since wage growth remains very modest in spite of this alleged shortage of qualified workers.

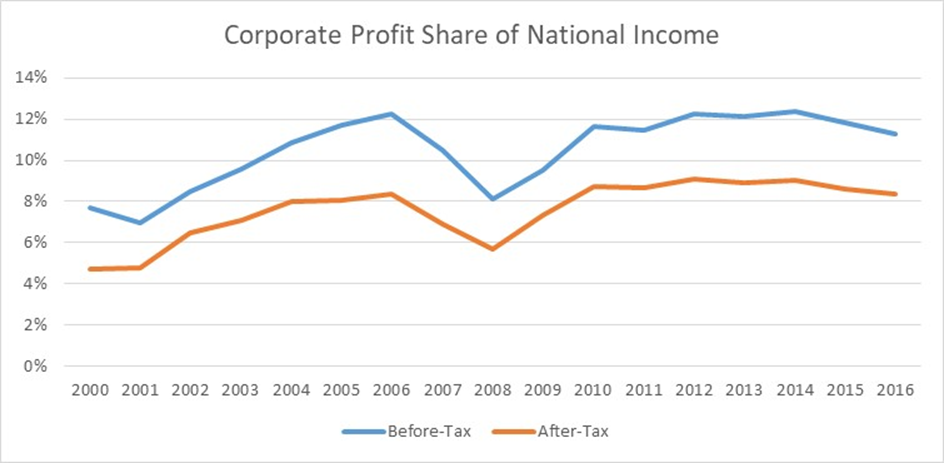

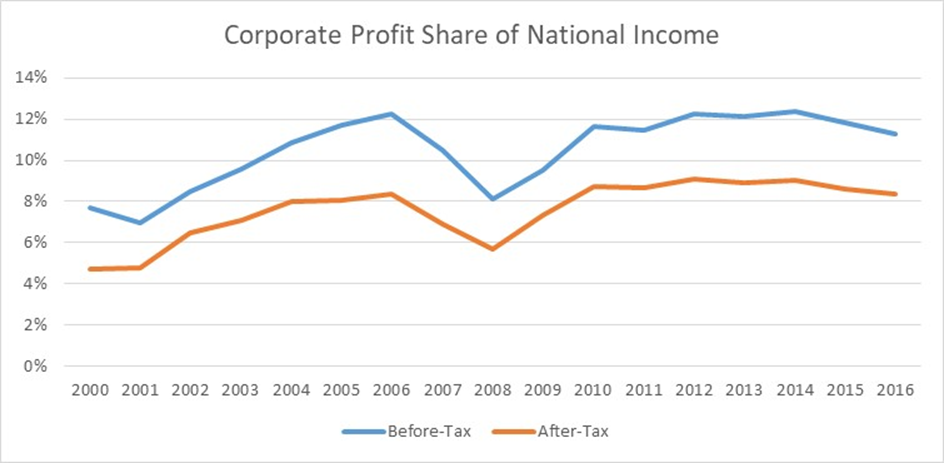

Businesses should be well-positioned to absorb higher wages since their profits have soared over the last two decades. In the years from 1980 to 2000, the beneficiaries of upward redistribution were higher paid workers like CEOs, Wall Street-types, and highly paid professionals like doctors and dentists. Since 2000, there has been a substantial shift from wages to profits, as the after-tax profit share of national income has nearly doubled, as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

The profit shares include one-third of the foreign profits of US corporations based on new research showing that this is really just profit shifting to evade taxes. If after-tax profit shares were back at their 2000 level, it would imply another $600 billion a year in wage income or almost $4,000 per worker in additional wages.

That’s the implication of this CNBC piece that claims that hiring is down because businesses can’t find qualified workers. If this is really the problem, then the solution, as everyone learns in intro economics, is to raise wages. For some reason, CEOs apparently can’t seem to figure this one out, since wage growth remains very modest in spite of this alleged shortage of qualified workers.

Businesses should be well-positioned to absorb higher wages since their profits have soared over the last two decades. In the years from 1980 to 2000, the beneficiaries of upward redistribution were higher paid workers like CEOs, Wall Street-types, and highly paid professionals like doctors and dentists. Since 2000, there has been a substantial shift from wages to profits, as the after-tax profit share of national income has nearly doubled, as shown below.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

The profit shares include one-third of the foreign profits of US corporations based on new research showing that this is really just profit shifting to evade taxes. If after-tax profit shares were back at their 2000 level, it would imply another $600 billion a year in wage income or almost $4,000 per worker in additional wages.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión