September 06, 2021

Last week’s jobs report filled news accounts with stories of gloom and doom. The 235,000 new jobs created in August was well below most projections. The theme was that something had gone seriously wrong with the economy and we should be very worried about the prospects for the labor market and the economy through the rest of this year into next.

While the jobs number was weaker than expected (my number had been 500,000), much of the pessimism in the reporting was a bit over the top. First, we know there is always some random movement in the monthly numbers. This is partly because of the errors in the survey and partly because of erratic patterns in employment. If a company hires a large number of workers in July, it will probably not turn around and hire a large number again in August.

It is likely that we were seeing this story to some extent with the August jobs report. We saw an extraordinarily rapid rate of job growth in June and July, with the economy reportedly adding 2,015,000 jobs, a number that was revised up by 135,000 with the August report. This translates into monthly job growth of 1,008,000 jobs.

It’s hard to know exactly how fast we should expect the economy to be creating jobs at this point, but let’s say 750,000 a month. That would translate into an annual rate of 9 million a year. That would get back the jobs lost in the pandemic in less than 8 months. It’s hard to argue that we should expect growth too much more rapid than this.

If we use 750,000 as a trend, then we were 515,000 above trend for the last two months. That means to stay on trend for the three-month period, we needed 235,000 jobs in August, exactly what we saw.

There clearly were surprises in this report. State and local governments lost 11,000 jobs in August after adding 246,000 in July. This left them down 815,000 jobs from the pre-pandemic level. This is most likely a matter of timing. Most of the decline in employment is due to fewer jobs in education. With nearly all schools returning to in-class instruction, presumably they will need roughly the same number of teachers and support staff as they had prior to the pandemic.

The restaurant sector was the other big surprise, shedding 41,500 jobs in August after adding 290,000 in July. Many commentators were quick to attribute this drop to the Delta Variant, with the idea that the fear of Covid kept people away from restaurants. This is far from clear. The Open Table data on reservations shows no clear trend, and its figure for the Sunday before Labor Day was 30.0 percent above the level from two years ago. There was also a gain of 35,500 jobs in the category of Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation. It is a bit hard to believe that people are comfortable going to concerts and seeing movies, but not eating at restaurants.

Clearly Covid had some effect, but it is at least as plausible that weak employment growth in restaurants is a supply-side story. The argument would be that many of the people who had formerly worked in restaurants are no longer willing to do so, or at least not at the same wages and working conditions. This would mean that these workers had the resources to be more selective on where they choose to work. This could be the case if they were able to save some of the $3,400 in pandemic checks that were paid out to single adults over the course of 2020 and 2021.

Remember, the average weekly earnings for production and non-supervisory workers in restaurants in 2019 was less than $340, so these pandemic payments were equal to ten weeks of normal pay. Also, with the $300 weekly supplements, unemployed restaurant workers likely had been getting more money than when they had been working. So, it shouldn’t seem far-fetched that many of these workers have more of a financial cushion now than they did before the pandemic.[1]

Consistent with this being more a supply-side story than a demand-side story is the fact that we are still seeing very rapid wage growth in the leisure and hospitality sector, which is overwhelmingly restaurant workers. The average hourly wage for production and non-supervisory employers rose at an annual rate of 23.7 percent in the last three months (June, July, August) compared with the prior three months (March, April, May). Over the last year, the hourly wage is up 12.8 percent.

Another item that fits this supply-side story is the fact that both the home health care sector and nursing homes lost jobs in August, 11,600 and 7,100 jobs, respectively. Both these sectors generally have low pay and poor working conditions, making them undesirable jobs.

In the same vein, the number of unincorporated self-employed is running more than 700,000 (7.1 percent) above the average for 2019. This suggests that many workers are considering alternatives to the types of jobs they held before the pandemic.

The Unemployment-Employment Picture

While the weaker than expected jobs numbers got most of the attention on Friday, the unemployment rate did fall another 0.2 percentage points to 5.2 percent. While no one should be satisfied with a 5.2 percent unemployment rate, it is important to recognize that, until recently, most economists would have viewed this as a very low unemployment rate. The unemployment rate did not fall to 5.2 percent following the Great Recession until July of 2015, at which point the Fed was preparing to raise interest rates to slow the economy, so that unemployment would not fall much further.

Last summer, before the passage of the American Recovery Act, the Congressional Budget Office projected that the unemployment rate would still be 8.0 percent in the third quarter of 2021, so we are doing considerably better than expected.

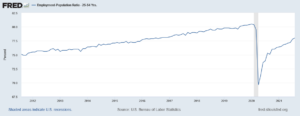

If we look at the employment side, as shown above, the prime age (ages 25 to 54) employment to population ratio (EPOP) rose 0.2 percentage points to 78.0 percent. This is a level not seen following the Great Recession until July of 2016, although 2.5 percentage points below the peak hit in January 2020, just before the pandemic.

By more narrow age groups, the largest falloff is among the 25 to 34 age group, with a decline in EPOP of 2.8 pp. The drop is slightly more for women than for men, 3.0 pp compared to 2.9 pp. For the 35 to 44 age group, the decline in EPOP was 2.7 pp. The falloff for men and women was almost identical, 2.7 pp and 2.6 pp. The drop in EPOPs for the 45 to 54 group was noticeably smaller at 1.9 pp. The decline for men in this age group was 1.8 pp compared with 1.9 pp for women.

The Economy Going Forward: Increased Worker Flexibility, Especially if the Biden Bill Passes

We still need to see more demand in the economy to create more jobs. It’s great if more workers have the bargaining power so that they can demand good jobs, and not be forced to accept work that offers low pay and bad conditions. If we continue to see the unemployment rate fall, then they may have the bargaining power to secure better pay and conditions, especially at the bottom.

Workers’ prospects will be further enhanced if Biden’s bill passes since it will hugely increase the amount of security they have. Workers will be able to count on support for child care and pre-K for their young children. They will also get subsidies that will ensure them affordable insurance through the exchanges created by Obamacare. And, they can count on a more generous Medicare program so that they will need less money to pay for their health care in retirement.

This will not be sufficient to reverse forty years of upward redistribution, but it’s a good start.

[1] There may have been a modest disincentive effect associated with the $300 weekly supplements, but most research indicated that this was relatively small. The effect of the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program, which made payments to people who would not qualify for traditional unemployment, may have been somewhat larger, however almost half the states have already eliminated these special pandemic benefits, and the federal program ends this month, so any disincentive effect will be dwindling rapidly.

Comments