The current global pandemic highlights the importance of paid leave for workers who are unable to work because of an illness or temporary disability, or because they need to care for a person with an illness or temporary disability. In a 2009 report, the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) reviewed paid sick leave policies in 22 countries ranked highly in terms of economic and human development. We found that the United States was the only country that did not guarantee that workers receive paid sick days or paid sick leave. Since then, several other countries included in our initial report have strengthened their standards for paid leave, including for self-employed workers, while the United States remains the outlier that provides no national guarantee.

In this report, we provide updated information on the availability of paid leave in these 22 countries. We focus on the availability of paid leave for workers who need to take at least two weeks of leave — 10 working days — to self-quarantine or get treated for COVID-19 symptoms. We document the main features of national paid sick leave policies in the 22 countries that provide basic coverage for such individuals. We also provide additional detail on paid sick leave policies in countries that have made changes since 2009.

This is a preliminary analysis we were able to conduct over the last few days. As policymakers respond to the pandemic, additional temporary changes are likely. The House of Representatives has just passed legislation that would require employers with fewer than 500 employees to provide paid sick leave to certain eligible employees during the pandemic, but only on a temporary basis. A growing number of other countries have taken (e.g., Canada, Ireland, Denmark, and the United Kingdom),1 or are in the process of taking (e.g., Sweden),2 steps to bolster their existing paid sick leave policies in response to the crisis, including by waiving waiting periods and medical certification requirements, and increasing benefit amounts.

We review paid sick days and paid sick leave policies in the United States and 21 other countries with high living standards according to the United Nations’ Human Development Index (HDI).3 While HDI rankings vary year-to-year, we examine the same 22 countries from our previous report: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. All these countries have confirmed COVID-19 cases as of March 16, 2020.4

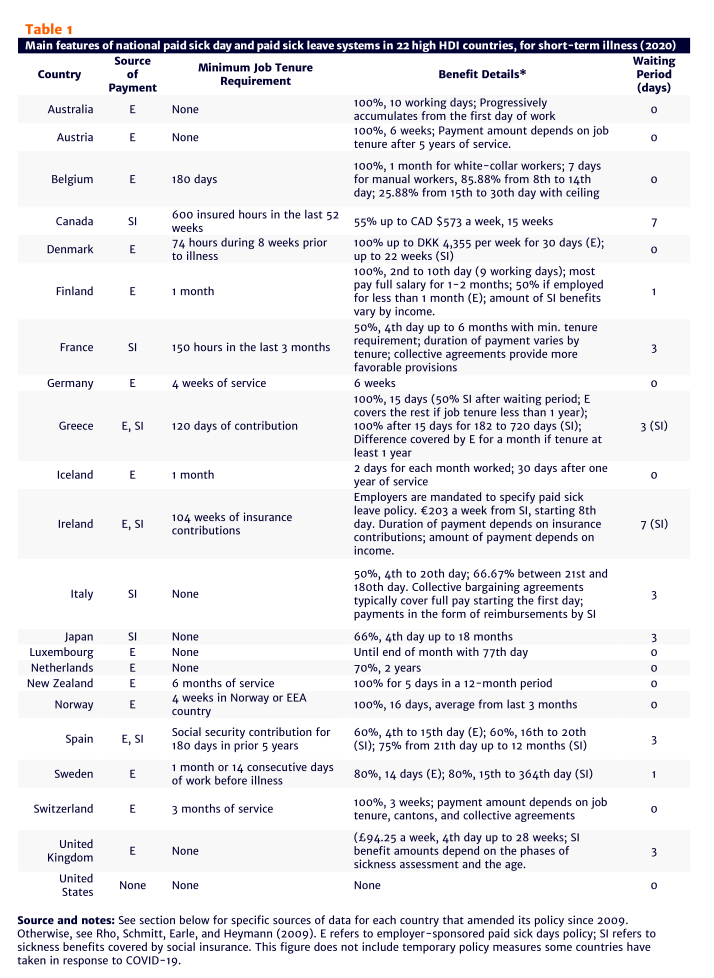

Table 1 below, shows whether each of the 22 countries provides a minimum national guarantee of paid sick days, the source of payment, the job tenure or other eligibility requirement for the benefit, the amount of wages that are required to be paid to eligible workers, and additional basic information.

These countries vary widely in how absence for short-term illness is governed. Many mandate employers to cover all or part of earnings lost by employees for short-term illness (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom). While government social insurance systems are in place for longer-term illnesses in many countries,5 some countries protect their workers through government social insurance systems, even for short-term illnesses (Canada, France, Italy, and Japan). Others have a hybrid of employer mandates and social insurance (Greece, Ireland, and Spain). Some countries, including Denmark, Finland, France, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, have collective bargaining arrangements that provide for more favorable terms of paid leave.6

To simplify the comparison of paid sick day policies across 22 countries, we calculate the full-time equivalent (FTE) pay7 the worker would receive if he or she is out sick for 10 working days. While some countries provide 100 percent of pay to all workers without a cap or a waiting period (Australia, Austria, Germany, Iceland, Luxembourg, Norway, Switzerland), others vary in their payment scheme. Ireland and the United Kingdom provide a set payment at the same rate to all workers, and Canada and Denmark have a benefit ceiling. In such cases, we use the OECD data8 on average wages for 2018 and multiply them by 0.85 to create estimated 2018 median national earnings levels in their national currencies.

Figure 1 shows the variation in FTE pay for a worker who makes the national median earnings, has less than three dependents, and has been employed for at least six months before the illness. While part-time or self-employed workers are eligible to receive sickness benefits in many of these countries, this calculation focuses on full-time workers. In a country that mandates employers to pay for 10 days at 100 percent, the FTE working days covered are 10 (e.g., Australia). If the employer sick days have a waiting period of one day but are covered for 10 days, the FTE working days covered are nine days (e.g., Finland). In a country whose social insurance benefits are paid for 10 days at 50 percent after a three-day waiting period, the FTE working days covered are 3.5 days (seven times the 50 percent replacement rate; e.g., Italy).

Workers in countries that have a benefit ceiling or a set payment receive a smaller share of pay if they make median national earnings: Canada (2.7 out of 10 days), Denmark (6), Ireland (1.3), and the United Kingdom (1.1). In these countries, however, workers making lower than median earnings would have a higher share of their average earnings covered. For example, a worker making £94.25 a week in the United Kingdom would see seven days of their sick days covered at 100 percent, after a three-day waiting period. Nine countries — Australia, Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Luxembourg, Norway, and Switzerland — pay for all 10 days should an average worker be out of work for any COVID-19 related illness. As can be seen, the United States is the only country that does not guarantee any FTE pay during a 10-day illness.

Figure 1

In 16 countries, national legislation that governs minimal paid sick days and leave remained unchanged in the last decade (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Finland, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States). Rho, Schmitt, Heymann, and Earle (2009) has more details on these provisions for each country. Six countries — Canada, Denmark, France, Ireland, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom — have either strengthened their policies or made amendments to their flat payment rate or the benefit ceiling. For this report, we focus on provisions that provide any coverage for a sickness-related absence from work that lasts for 10 working days. Where applicable, we also discuss temporary policy measures that some countries have taken in response to COVID-19.

Canada provides Employment Insurance (EI) sickness benefits for up to 15 weeks. This benefit is available to eligible claimants who are unable to work because of illness, injury, or quarantine. To qualify, workers must have worked at least 600 hours in the 52 weeks before the illness and show that their pay has been reduced by more than 40 percent for at least one week.

EI beneficiaries can receive 55 percent of their earnings up to a maximum of CAD $573 a week. EI beneficiaries living in a low-income family (annual net income of $25,921 or less) are also eligible for the EI Family Supplement, which increases their total EI benefit up to a maximum of 80 percent of average earnings.

There is a one-week waiting period for benefits; this is a reduction from the two-week waiting period in place before 2017.9 Moreover, in response to COVID-19, Canada is waiving the one-week waiting period.10 Thus, all eligible employees who take leave to self-quarantine will be paid starting from the first day of leave. Self-employed workers would also qualify for the waiver if they are registered to participate in EI.11 Canada is also temporarily waiving the requirement to provide medical certification of illness for workers in quarantine.

For employees working in a federally regulated workplace, Canada now guarantees three days of paid “personal leave” that can be used for sick leave or various other purposes (these workers are also entitled to unpaid leave for illness or other purposes). To qualify for paid leave, workers must have worked at least three consecutive months before taking leave.12 For hourly workers taking paid leave, pay is determined by average daily earnings for 20 days prior to the sickness, excluding overtime.13

Only 6 percent of all Canadian workers are working in a federally regulated workplace.14 For the rest of the Canadian workforce, paid sick days are a matter of provincial and local law. While most jurisdictions have sickness-related provisions, they are mostly unpaid, except in Quebec, which guarantees two days of paid leave after three months of continuous work.15

In Denmark, employers must provide paid sick leave for the first 30 days of an employee’s illness for employees who have worked at least 74 hours during the eight weeks prior to taking leave. While the benefit is calculated on the basis of average pay in the last three months before the illness (for both full- and part-time workers), the payment may not be covered in full because of a cap of DKK 4,355 per week as of 2019.16 In response to COVID-19, the government will reimburse employers for providing salary or sickness benefits to employees on leave due to COVID-19-related illness or quarantine, from the first day of the leave.17

After the first 30 days, the benefit is paid by the employee’s local government for up to 22 weeks within a nine-month period. For self-employed workers, the local government pays for the leave after two weeks of sickness, unless the individual has paid voluntary contributions.

Finland requires that employers pay employees with at least one month of service from the second day of illness to the tenth day of illness, for nine working days.18 For those who have worked for less than a month, employers must provide 50 percent of their pay.

Under France’s universal health care system (Protection Universelle Maladie, PUMa), employees are eligible to receive daily cash benefits of 50 percent of their basic daily wage for up to six months (after a three-day waiting period). To be eligible, employees must have worked at least 150 hours in the preceding three months before their illness. Benefits may continue beyond six months if the employee has worked for at least 600 hours during the preceding 12 months.19 This daily cash benefit can be received up to 360 days in a three-year period. Workers with more than two dependent children receive 66.7 percent of earnings after 30 days. The basic daily wage is calculated based on the three months of salary prior to the illness, with a cap of 1.8 times the monthly minimum wage, or €2,738.19 per month as of January 1st, 2019.20

In France, employment contracts or collective bargaining agreements typically provide more favorable provisions. Under collective agreements, employees with more than one-year tenure are typically covered for at least 90 percent of their earnings for 30 days (full payment in the case of Alsace-Moselle) and two-thirds of earnings for the following 30 days.21

Ireland mandates employers to specify paid sick leave policy in their contracts. Workers can also claim Illness Benefit from the Department of Employment Affairs and Social Protection (DEASP) if they have at least 104 weeks of social insurance contributions paid. The waiting day is currently six days, excluding Sunday. Starting the following week, the Illness Benefit is €203 a week for those making €300 or more, up to two years with 260 weeks social insurance contributions paid, and up to one year with 140 to 259 weeks of contributions paid. The rates vary by average weekly earnings and number of dependents.22 In response to COVID-19, the waiting period and the normal social insurance contribution requirements for eligibility will be waived and the Illness Benefit is increased to €305 a week.23

Employee’s Health Insurance, Japan’s statutory health insurance program for workers who do not have employer-based coverage, includes a sickness and injury allowance. Eligible workers receive 66.67 percent of their average daily basic wage in the previous 12-month period.24 There is a three-day waiting period, and covered employees can receive benefits for up to 18 months. While self-employed individuals have health insurance coverage through National Health Insurance, they are not covered when sick. Under the Labor Standards Act, Japanese workers are protected from dismissal from work (and for 30-days thereafter) for absences related to injuries and illness at the time of employment.

Starting in January 2019, Luxembourg requires that employers pay full salary from the first day of illness to the end of the month of which the 77th day of illness falls on, during a reference period of 18 months.25 For illnesses beyond 77 days, the National Health Fund (Caisse Nationale de Santé – CNS) provides cash benefits up to 78 weeks during a reference period of 104 weeks.26

In the United Kingdom, employers provide Statutory Sick Pay (SSP) of £94.25 per week for up to 28 weeks. Individual employers may provide a higher sick pay depending on the employment contracts. There is a three-day waiting period to receive the benefits.27

The SSP can be claimed for self-isolation due to COVID-19,28 and for those who are not eligible, such as self-employed workers or those making less than an average of £118 per week, Universal Credit (UC) or Employment and Support Allowance are available for a claim. 29

At the time we published our 2009 report, five states (CA, HI, NJ, NY, and RI) and Puerto Rico had temporary disability insurance (TDI) programs, and two cities (San Francisco and Milwaukee) required employers to provide paid sick pay to eligible employees. Since then, a growing number of states and cities have adopted paid family and medical leave programs and/or paid sick day requirements.

Today, all state TDI programs remain in place and provide benefits to eligible workers after a seven-day waiting period. Four of the five states with TDI programs in 2009 (CA, NJ, NY, RI) have adopted paid family leave benefits that are administered through their TDI programs. Four additional states — CT, MA, OR, WA — and the District of Columbia have adopted paid family leave legislation, but effective dates vary. Washington State’s program started accepting applications and paying benefits on January 1, 2020. DC’s program will start accepting applications and paying benefits on July 1, 2020. The three other states will not start paying benefits until after 2020. For an overview of state paid family and medical leave laws, see the National Partnership for Women & Families’ State Paid Family and Medical Leave Insurance Laws. All state paid family and medical leave laws allow covered workers to take paid leave to care for themselves during a temporary disability or illness, and allow covered workers to take paid leave to care for family members with a serious illness.

Twelve states — AZ, CA, CT, MD, MA, MI, NV, NJ, OR, RI, VT, and WA — currently require employers to provide paid sick pay to eligible employees. These laws typically apply to both public and private employers and require employers to accrue an hour of sick leave for every 30 to 40 hours worked per year. The maximum hours of leave that a worker can accrue per year is typically capped (or left to employers’ discretion to cap) at 40 hours per year. For an up-to-date overview of these laws, see the National Council of State Legislature’s “Paid Sick Leave.”

In addition, 23 cities and counties in California (San Francisco, Oakland, Emeryville, Santa Monica, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Berkeley), Illinois (Chicago and Cook County), Maryland (Montgomery County), Minneapolis (Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Duluth), New York (New York City and Westchester County), Pennsylvania (Philadelphia and Pittsburgh), Texas (Austin, San Antonio, and Dallas), Washington (Seattle and Tacoma), and the District of Columbia, have laws in effect now to provide paid sick days for personal illness or to care for a sick family member. These changes are tracked by A Better Balance, the National Partnership for Women & Families, and other national advocacy organizations.

In response to COVID-19, Philadelphia passed a “declaration of extraordinary circumstance”, which would allow workers to use their paid sick time (up to five days if they work for employers with more than nine employees) if they were to stay home for self-quarantine, business closures, or to care for a child due to a school closure.30 New York announced an agreement to extend the paid sick leave bill that would guarantee job protection and paid leave for the duration of the quarantine.31 While these measures may not be sufficient for many workers, they are an important step forward.

Unlike the 21 other rich economies in the world, the United States does not guarantee any form of paid sick days or leave. It is ever more important to address this long-standing policy gap by adopting a federally mandated employment standard that would last beyond a public health emergency.

“Average Annual Wages,” Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development, accessed March 17, 2020, https://stats.oecd.org/viewhtml.aspx?datasetcode=AV_AN_WAGE&lang=en

“Backgrounder: Employment Insurance Waiting Period,” Department of Employment and Social Development, Government of Canada, last modified November 13, 2018, accessed March 16, 2020,https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/news/2018/11/backgrounder-employment-insurance-waiting-period.html

Canada Labour Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. L-2, s.7.https://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/L-2/index.html

Heymann, Jody, Hye Jin Rho, John Schmitt, and Alison Earle, “Contagion Nation: A Comparison of Paid Sick Day Policies in 22 Countries,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, May 2009. https://cepr.net/documents/publications/paid-sick-days-2009-05.pdf

“Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)–Cases and Latest Updates,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States Federal Government, last modified March 16, 2020, accessed March 17, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/world-map.html

“Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)-Employment and Social Development Canada,” Department of Employment and Social Development, Government of Canada, last modified March 13, 2020, accessed March 16, 2020,https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/notices/coronavirus.html

“COVID-19 – Employment Law Aspects of the Current Lock-Down Situation in Denmark,” Kromann Reumert, last modified March 13, 2020, accessed March 17, 2020, https://www.kromannreumert.com/Nyheder/2020/03/COVID-19-Employment-law-aspects-of-the-current-lock-down-situation-in-Denmark

The Canadian Press, “How EI Benefits for COVID-19 Quarantines Will Work under the New Rules,” National Post, March 13, 2020,https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/canada-sick-leave-ei-benefits-coronavirus

“Denmark–Sickness Benefit,” Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, European Commission, accessed March 16, 2020,https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1107&langId=en&intPageId=4489

Employment Contracts Act, Amended 2018, (FI), accessed March 16, 2020, http://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/2001/en20010055.pdf

Employment Insurance Act No. 116 of 1974, Amendment of Act No. 30 of 2007, (JP), Accessed March 16, 2020 http://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/law/detail/?id=1910&vm=04&re=01

“Employment Insurance Sickness Benefits–Receiving Your EI Sickness Benefits,”Department of Employment and Social Development, Government of Canada, last modified January 2, 2020, accessed March 16, 2020, https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/ei/ei-list/reports/sickness.html#h2.4

Families First Coronavirus Response Response Act, H.R.6201, 116th Cong. (2020).

“France–Health Benefits in Cash,” Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, European Commission, accessed March 16, 2020,https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1110&langId=en&intPageId=4535

“Governor Cuomo Announces Three-Way Agreement with Legislature on Paid Sick Leave Bill to Provide Immediate Assistance for New Yorkers Impacted By COVID-19,” Governor of New York, New York State, last updated March 17, 2020, accessed March 17, 2020, https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-announces-three-way-agreement-legislature-paid-sick-leave-bill-provide-immediate

United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report 2010: The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development, November, 2010, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/270/hdr_2010_en_complete_reprint.pdf

“Illness Benefit,” Citizen Information Board, Government of Ireland, last modified March 15, 2020, accessed March 16, 2020,https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/social_welfare/social_welfare_payments/disability_and_illness/disability_benefit.html

“Illness Benefit for COVID-19 Absences,” Department of Employment Affairs and Social Protection, Government of Ireland, accessed March 16, 2020, https://www.gov.ie/en/service/df55ae-how-to-apply-for-illness-benefit-for-covid-19-absences/

“Luxembourg–Sickness Cash Benefits,” Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, European Commission, accessed March 16, 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1120&langId=en&intPageId=4678

“New Changes Regarding Employees on Sick Leave,” News, Government of Luxembourg, updated January 1, 2019, accessed March 16, 2020, https://guichet.public.lu/en/actualites/2019/Janvier/08-nouveaute-maladie-salarie.html

“Paid Sick Leave,” National Conference of State Legislatures, last updated March 5, 2020, accessed March 17, 2020, https://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/paid-sick-leave.aspx

“Personal Leave,” Department of Employment and Social Development, Government of Canada, last modified November 1, 2019, accessed March 16, 2020, https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/services/labour-standards/reports/personal-leave.html

“Sickness or Accident,” Commission des normes, de l’équité,de la santé et de la sécurité du travail, Government of Québec, accessed March 17, 2020, https://www.cnt.gouv.qc.ca/en/leaves-and-absences/sickness-or-accident/index.html

Nordic Social Statistical Committee, Social Protection in the Nordic Countries, 2017, https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1148493/FULLTEXT02.pdf

Reyes, Juliana Feliciano, “Philadelphia Just Extended Its Paid Sick Leave Law to Cover Public Health Emergencies Such as Coronavirus,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, March 16, 2020, accessed March 17, 2020, https://www.inquirer.com/health/coronavirus/philadelphia-paid-sick-leave-law-coronavirus-public-health-emergency-20200316.html

Social Security Administration, Social Security Programs Throughout the World: Asia and the Pacific, 2018, March 2019, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/progdesc/ssptw/2018-2019/asia/japan.pdf;

“State Paid Family and Medical Leave Insurance Laws,” National Partnership for Women and Families, August, 2019, accessed March 17, 2020, https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/economic-justice/paid-leave/state-paid-family-leave-laws.pdf

“Statutory Sick Pay,” UK Government, accessed March 16, 2020https://www.gov.uk/statutory-sick-pay

“Support for those affected by COVID-10,” UK Government, accessed March 18, 2020 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/support-for-those-affected-by-covid-19/support-for-those-affected-by-covid-19

“The Coronavirus/Covid-19 – Applicable Regulations,” Försäkringskassan, Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, accessed March 17, 2020, https://www.forsakringskassan.se/privatpers/!ut/p/z1/dYzBCoJAFEW_xmW-Z2Mh7cTAsKDChfY2MeJrHJQZGaeCvj6hXdTdncu5FwhqICMfWkmvrZHDzBdaX-PdNovyDPdJLlaYnk-RiI_LoigRKiCgWcE_SREKIDXY5vOWmkYkCsjxjR278O7muvN-nDYBBsgmfOpej9xqGVqnAvw16uzkof52oWQDY29eB64Wb8eLAlw!/?1dmy&urile=wcm%3apath%3a%2Fcontentse_responsive%2Fprivatpers%2Fcorona-det-har-galler

“The French Social Security System: Health, Maternity, Paternity, Disability, and Death,” Centre des liaisons européennes et internationales de sécurité sociale (CLEISS), Government of France, accessed March 16, 2020,https://www.cleiss.fr/docs/regimes/regime_france/an_1.html