April 06, 2017

March 27, 2017, Dean Baker

Remarks by Dean Baker, Co-Director, Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR)

Keynote presentation at the Annual Forum World Bank’s Macroeconomics and Fiscal Management Global Practice

March 27, 2017

Introduction

The growth of populist movements across the world is impossible to ignore at this point. The last decade has seen a huge expansion in support of populism of both the right and left, although populism of the right is generally much stronger.

This populist surge has been behind the decision of the United Kingdom to leave the European Union, parties challenging for power on the right in France and Italy, as well as several smaller European countries, and on the left in Spain. Left populists actually managed to gain power in Greece. And of course populist sentiments were a major force in the election of Donald Trump, as there was a massive swing in support among white working class voters towards the Republicans in the last election.

While it is hard to put together a coherent economic agenda from populist platforms, there are some common themes. The populist message, from the both the left and right, is that the typical person is not getting their share of the benefits of economic growth. The left populists generally blame some set of corporate elites, the right generally turns to immigrants and racial and ethnic minorities as their villains. The populists of the right usually promise to put their national group above the foreign elements who are seen as the threat, thereby restoring prosperity to true French people, Italians, Americans or whoever.

While there can be little basis for sympathy for the racism and xenophobia pushed by right-wing populist leaders, there is a real economic basis for the anxiety of the groups to whom they are appealing. We have to take this anxiety seriously, not only because it threatens the future of democracy, but we as economists deserve much of the blame.

In fact, economies in the rich countries have not produced real benefits for much of the population in recent decades. This is certainly true for most rich countries for the last fifteen years, and in the United States, arguably for the last four decades. The failure to deliver growing incomes for the large segments of the population was not the result of natural forces, but rather conscious policy decisions. I will argue that it is important that we steer rich country governments on a different course, both because it is the right thing to do — policies should not be designed to redistribute income upwards — and also to preserve democracy. We cannot expect the bulk of the population to support governments that do not improve their quality of life.

I will make three main points in this discussion. First, I want to outline the extent to which economic policy in rich countries has failed both to produce growth in aggregate and in particular failed to deliver gains to those in the bottom half of the income distribution. The second point is that this failure is linked to the growth of populist forces. The third and most point is that we can devise alternative policies that are both growth enhancing and also will promote greater equality.

Rich Country Economic Policy: Stagnation and Inequality

Both the economic crisis in 2008 and the weak recovery that followed caught the overwhelming majority of economists by surprise. The fact that asset bubbles were driving growth across much of the world was overlooked by almost the whole profession. None of the official forecasts predicted the recession in 2008 and 2009. In fact, most forecasters failed to recognize the recession, and certainly not its severity, until it was well under way. This mistake was compounded by failing to recognize the weakness of the recovery. The conventional view was that there would be a quick bounce back from a severe recession, as had been the case following prior downturns.

For example, in the spring of 2009 the International Monetary Fund (I.M.F.) projected that growth in Italy would average 1.2 percent for the years 2011-2013, for France it projected average growth of 1.9 percent, and for the U.S. 3.5 percent (International Monetary Fund, 2009). The actual figures ended up being an average of -1.3 percent annual growth for Italy, 0.9 percent for France, and 1.8 percent for the United States (International Monetary Fund 2016).

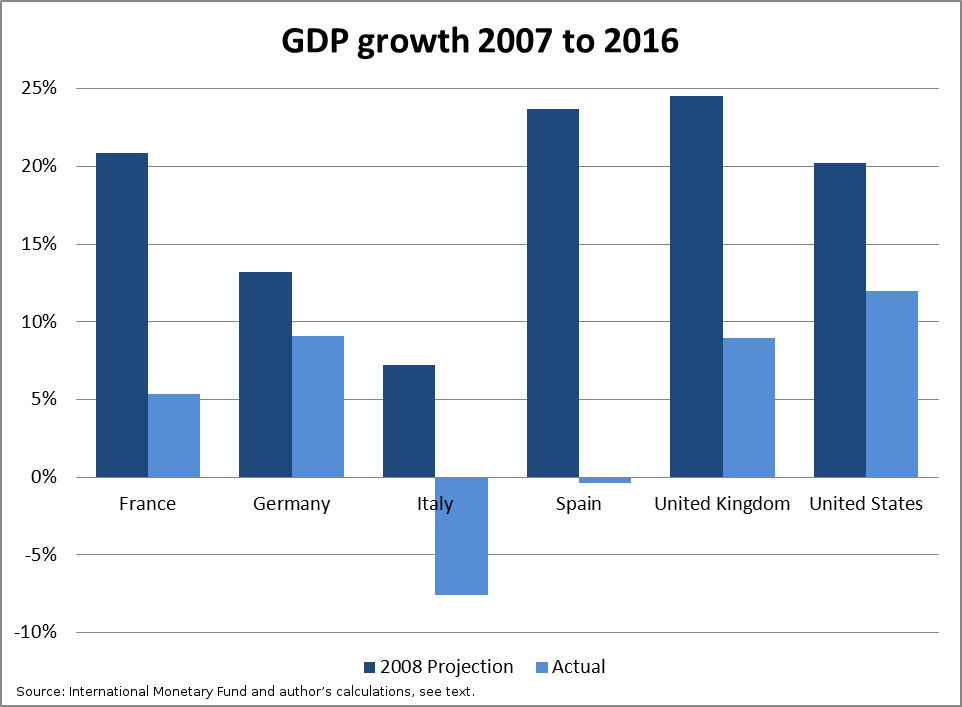

The net effect of failing to see the economic crisis in 2008 and 2009, and badly over-estimating the pace of the recovery, was that the economies of every major wealthy country hugely underperformed its projected growth path from the pre-crisis period. Figure 1 compares the I.M.F.’s projected growth for the years from 2007 to 2016 from April of 2008, with the actual growth path for this nine year period.1 Among the countries shown, Germany’s actual growth is closest to projected, although it still lags by 4.1 percentage points. In the United States the gap is 8.3 percentage points, in France it is 15.6 percentage points, and in Spain it is 24.1 percentage points.

This represents a massive falloff in growth from the projected path. If we give the I.M.F. economists credit for producing reasonable projections of these economies’ growth potential in 2008 (other forecasters had similar projections) then the growth shortfall in subsequent years should be viewed as a result of policy failures. In other words, had good policy been pursued to prevent the crisis in the first place and/or to respond more aggressively once it hit, these economies could be on a growth path close to what had been projected before the crisis hit.

This growth shortfall by itself would provide a real basis for public dissatisfaction with the conduct of economic policy. After all, mistaken policies that needlessly cost a country several percentage points of GDP are a big deal. When these policies lead to double-digit losses in GDP on an ongoing basis, as is true for many wealthy countries, that provides genuine grounds for the public to be unhappy with those designing economic policy.

However there are even more grounds for anger when the weak overall growth performance is accompanied by an upward redistribution of income. This is exactly what we have seen in most wealthy countries. A recent analysis by the OECD (2015) showed that almost all wealthy countries have seen a rise in inequality in the last two decades. In several cases, the growing share of income going to the wealthy actually has been associated with declines in income for those at the middle and bottom of the income distribution.

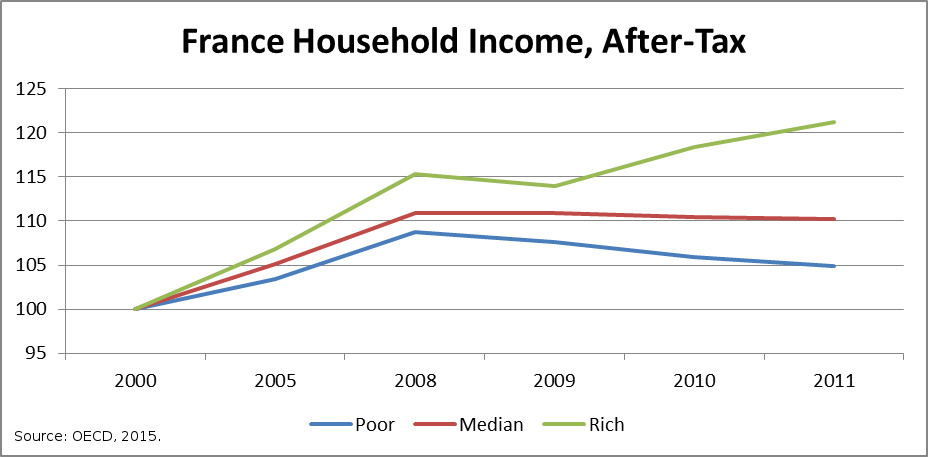

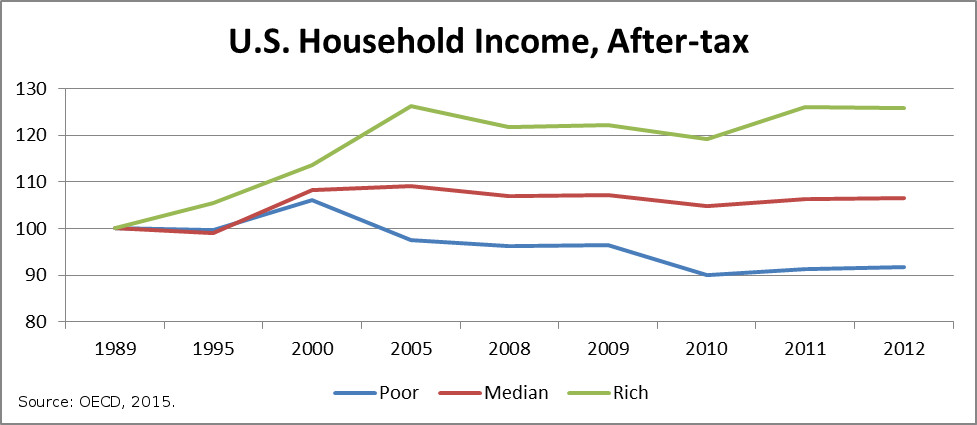

Figure 2 shows the changes in after-tax household income for the top decile, the median household, and the bottom decile for France, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The data for France show real income growth for the wealthy outpacing the growth for the median household and the poor between 2000 and 2008, although median household income rose by almost 11 percent over this period, and income for the poor rose by almost 8.0 percent. However, in the years since 2008 median income has dipped slightly, while income for the poor has fallen by 3.4 percent, even as income for the wealthy has risen rapidly. These data end in 2011, but it unlikely the picture has improved in the last six years for most of the population, given the country’s continued weak growth.

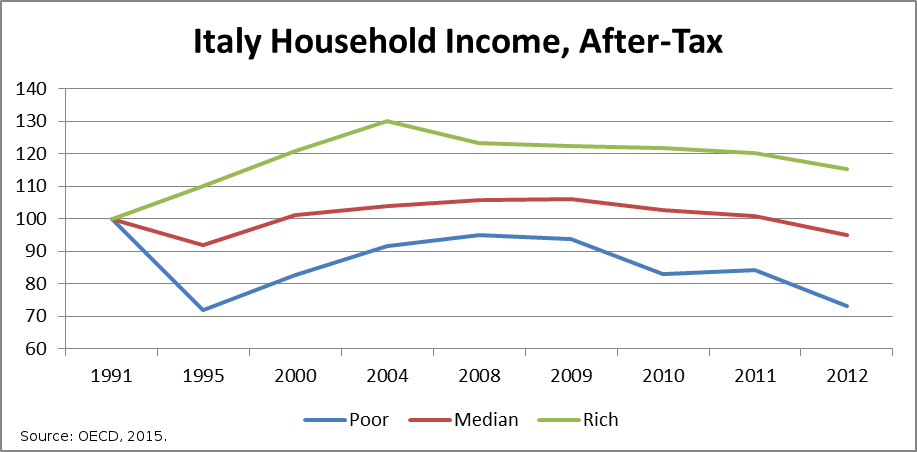

The picture for Italy is far more grim. The data show that median household income in 2012 was down by more than 5 percentage points from its 1991 level. The income of the bottom tenth had fallen almost 27 percent over this period. The income of the top tenth had risen by 15 percent since 1991.

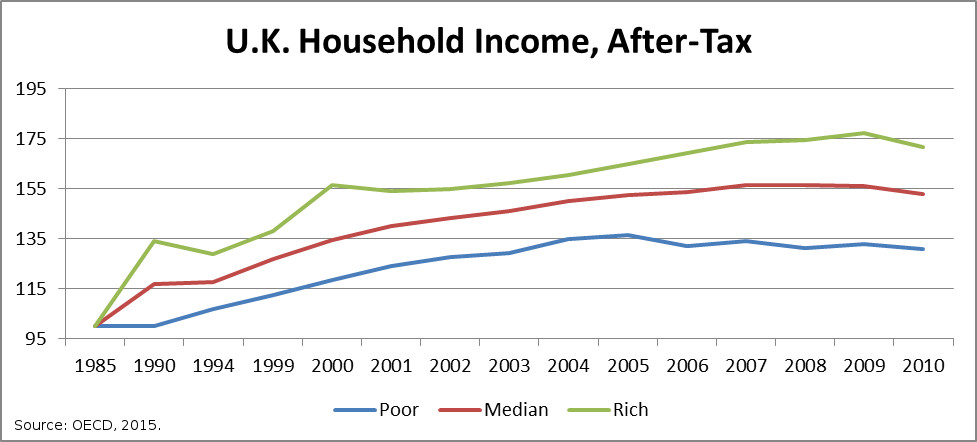

The data for the U.K. show substantial income gains for the poor and median between 1985 and 2007, but not as much as for the richest 10 percent. Income for the poor rose by 34 percent over this period, while income for the median household rose by almost 57 percent. However income for the top decile rose by more than 73 percent. Since 2007 income for the poor and the median household are both down by roughly 2.5 percent, although income for the rich also had a slight drop since 2010. Unfortunately, these data end in 2010, but it is unlikely this pattern was reversed, with the UK seeing very weak growth in subsequent years.

In the United States income of the poor is down by more than 8.0 percent from its 1989 level. Median household income is slightly above its 1989 level, but it had not recovered to 2000 level as of 2012. Household income for the wealthy was up more than 25 percent over from 1989 to 2012.

The OECD data shows a similar story of growing inequality for other countries as well. In the Netherlands, as a result of weak growth and upward redistribution, median household income in 2012 was slightly below its 2000 level. This combination left median household income in Greece in 2012 more than 13 percent below its 1986 level.

In short, recent decades have not been good economic times for most of the people in the rich countries. When large segments of the population are seeing little or no gains from the economy for a substantial period of time, it is not surprising that they would look to throw out the people who they consider responsible. This is especially likely when they see a relatively small group at the top who appear to be doing very well even as the rest of the country does poorly.

The Motivation for Populism: Racism and Xenophobia or Economic Hardship

There has been a major debate in the last year over the extent to which the upsurge in populist sentiment can be attributed to economic factors, as opposed to a resurgence of racist and xenophobic sentiment. The two cannot easily be disentangled, since many people, particularly those who are less knowledgeable about policy, may mix motives in their minds. I don’t expect that this argument can be conclusively resolved, but there are a few simple points that can be made.

First, racism and xenophobia are not new in any of the countries which have seen an upsurge in right-wing populism. The burden on those who would see these as the key factors behind the rise of populism, and especially right-wing populism, is to explain why it has suddenly become such a large political force. Immigration of non-white people to Europe is hardly a new phenomenon. The influx of refugees from Syria and other Middle Eastern countries has been somewhat of a flashpoint, but the rise of populism preceded this influx.

The terrorist incidents in France, Belgium, and elsewhere also have fueled racist and xenophobic attitudes, but again such incidents are not unprecedented and cannot be closely tied to the rise of right-wing populism. Perhaps the most deadly single terrorist attack in recent decades occurred in Madrid in 2004, nonetheless right-wing populism is not a major political factor in Spain. While nowhere has been immune from terrorist attacks, countries like Denmark and the Netherlands have seen strong upsurges in right-wing populism with relatively few incidents.

It is possible to point to political causes in these two cases, as the social democratic parties have been proponents of cuts to welfare state benefits, whereas populist parties have been vigorous supporters of maintaining or strengthening welfare state benefits. This is especially notable in Denmark, where the Danish People’s Party repeatedly threatened to withdraw support from conservative governments if they made large cuts in health and education funding.

While racism and xenophobia were undoubtedly important factors in the recent Brexit vote, the supporters of Brexit made explicit economic arguments to advance their case. They promised in a national ad campaign that the money saved on the United Kingdom’s contribution to the European Union could be used to shore up the national health system (NHS) if the UK left the EU. While this was not true, the net direct savings were trivial and in any case the UK is not facing a hard budget constraint in its national spending (in other words, cutting back funding for the NHS was a political choice, not an economic necessity) , it seems likely that many people believed it. It is also the case that the quality of health care in the UK has been affected by recent budget cuts. Given these facts, it is reasonable to believe that concern over the quality of the health care system was a major factor for many supporters of Brexit, who tended to be older, and therefore more in need of health care, and lower income.

The U.S. case also provides a difficult challenge to those who want to argue that the issue is simply one of resurgent racism or xenophobia. After having elected an African American president twice, we have to believe that large segments of the white population suddenly became more worried about losing control of the country to non-whites. The immigration story is even less plausible as an explanation in the U.S. than Europe, as immigration has actually slowed substantially in the years since the Great Recession.

In addition to being more openly racist and xenophobic than prior Republican candidates, Trump also distinguished himself from them in being explicitly protectionist. He put reversing “bad” trade deals at the center of his economic agenda. He argued that we lost good paying manufacturing jobs to other countries because our trade negotiators were stupid and got outmaneuvered by the negotiators from Mexico, China, and elsewhere. He promised that he would get good trade deals by threatening or actually imposing large tariffs. He told voters that he would bring back the millions of manufacturing jobs that had been lost to trade.

While this promise may be completely unrealistic, it certainly seems plausible that many voters took it seriously. The key to the election was the flipping of the Midwestern industrial states that had lost a huge percentage of their manufacturing jobs due to the rise in the trade deficit in the last two decades. The state of Ohio, which President Obama had won by comfortable margins twice, went to Trump by over eight percentage points. Trump also carried Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania, all of which had voted Democratic in every election since 1988.

There is considerable evidence that Trump saw the greatest improvement in performance relative to prior Republicans in areas that have fared worst in the last two decades. For example, a recent study examined the correlation between deaths due to drugs, alcohol, and suicide, and found that the counties with the highest rates were also the ones where Trump most over-performed relative to prior Republican candidates (Monnat 2016). Other analyses produced similar findings correlated counties with rising mortality rates with Trump voters in the Republican primaries (e.g. Guo 2016).

Perhaps the most compelling case against these lines was a paper by David Autor, David Dorn, Gordan Hanson, and Kaveh Majelsi (2017) that built on their prior work analyzing the impact of imports from China on manufacturing and total employment by commuter zone. Their analysis found a strong correlation between the exposure to imports from China and the shift from Democratic to Republican votes in the 2016 presidential election compared with the 2000 presidential election. By their estimates, if the rise in imports from China had been half as large as what the country actually experienced, Clinton would have carried North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan, giving her a victory in the Electoral College.

There is one final point about the relationship between the economic prospects of less-educated workers and electoral outcomes that is worth noting. The big change in the 2016 U.S. presidential election compared with prior elections was the huge margin that Trump held among non-college educated whites, while carrying college educated whites by a smaller margin than prior Republican candidates. One outcome of a relative deterioration in the prospects of less-educated workers has been a slower rate of growth in the number of college graduates in the United States in the last four decades.While the cause of this slowdown is debated, there is no question that the rate of increase in the percentage of young people graduating from college has slowed markedly.

If college graduation rates for whites had continued to grow in the years since 1979 as they had done in the years between 1959 and 1979, at the time of the 2016 election we would have had 7.2 million more white male college grads 3.2 more female college grads, with corresponding declines in the number of non-college educated whites (Baker and Rawlins, 2017). Trump carried non-college educated white males by a margin of 48 percentage points. He carried college educate white males by 4 percentage points. Trump carried non-college educated women by 14 percentage points, while losing college educated women by 7 percentage points.

If we assume that the voting patterns among these groups did not change, but the educational mix of the white population changed at the same rate in the last four decades as it did between 1959 and 1979, Clinton’s popular vote margin would have been 1.8 million larger, virtually guaranteeing her a comfortable victory in the Electoral College. In short even if attitudes of less-educated white voters were exactly the same in 2016, greater economic progress for those in the middle and bottom would have kept Donald Trump from winning the presidency.

Different Political Outcomes from Alternative Economic Policies

The prior discussion is only interesting if there is an alternative economic path that would have produced better outcomes for the bottom portion of the income distribution. While it is common to argue that the upward redistribution of the last four decades is part of an inevitable process of globalization and the development of technology, I would argue that it has been the result of economic policy choices.2 I will discuss five areas in which alternative economic policies could have led to greater equality without slowing overall growth:

-

Macroeconomic policy — governments have been over-concerned about the threat of inflation at the cost of higher unemployment;

-

Intellectual property rights — there has been a notable strengthening of intellectual property rights in a variety of areas, leading to larger incomes for those in a position to benefit from rents in this area;

-

The growth of finance — there has been an explosion in the size of the financial sector relative to the economy as a whole. This sector is the source of some of the highest incomes in the economy;

-

Corporate governance — the rules of corporate governance have allowed CEOs and other top executives to command an ever larger share of output;

-

Protection of high end professionals — doctors and dentists have seen enormous growth in their pay relative to other workers, in part because they are largely protected from foreign and domestic competition.

My discussion of these topics is necessarily brief, but hopefully will be sufficient to outline the basic case. It is also focused on the situation in the United States, both because this is the country which I know best and also because it is the extreme case in terms of the upward redistribution of income.

Macroeconomic Policy

At this point there is a large body of evidence indicating that macroeconomic policy was excessively contractionary in the years following the economic crisis (Blanchard and Leigh, 2013; I.M.F. 2010). The implication is a belief in the need for fiscal austerity and a possible resurgence of inflation resulted in policies that needlessly slowed growth and raised unemployment. This loss of output had lasting effects through hysteresis as lower rates of growth reduced private and public investment. In addition, some of the long-term unemployed became unemployable as a result of their detachment from the labor market (DeLong and Summers, 2012). It is easy to envision a scenario in which more expansionary fiscal policy would have allowed countries to recover more quickly, following paths closer to what had been projected by the I.M.F. at the depth of the recessions. This would imply output in 2017 that is several percentage points higher than its current level.

There is also reason to believe that the benefits of higher output would disproportionately go to those at the middle and the bottom of the wage distribution. Baker and Bernstein (2013) find a strong inverse correlation between unemployment rates and real wage growth for the bottom half and especially the bottom quintile of the wage distribution. In the current cycle there has been a sharp redistribution from wages to profits, as a result of the weakened labor market. The profit share of corporate income was more than 5.0 percentage points higher in 2013 than its peak in the 1990s cycle. Roughly half of this rise has been reversed as the labor market has tightened in the last three years. It is reasonable to believe that much of the rest of this redistribution will be reversed if monetary policy does not prevent further tightening.

It is also worth pointing out that economic collapse itself was the result of failed policy. It was possible to recognize the housing bubbles that were driving the economy in the United States, Spain, Ireland, and elsewhere (Baker 2002). In the United States, there was no precedent for the sort of run-up in house prices seen in the bubble years. It clearly was not driven by the fundamentals of the housing market, as rents largely tracked the overall inflation rate in these years. It was also clear that the bubble was driving the economy as residential construction hit a record share of GDP and a housing wealth driven consumption boom pushed the saving rate to a record low.

For these reasons, it should have been apparent that the bubbles were likely to burst and have serious consequences for the economy. It was possible to reject the idea that it would be a simple matter to pick up the pieces with stimulatory monetary policy even before the crash. The failure to recognize and counter the growth of dangerous asset bubbles was a policy failure, not a fluke natural event that could not be prevented. The public has good cause to be unhappy with the performance of people in policy positions in these years and to blame them for the pain that they have endured as a result.

Intellectual Property Rules

It is striking how frequently the upward redistribution of the last four decades is attributed to technology, as though the distribution of benefits from technological progress is itself determined by technology. This is clearly not true, since the ownership claims to technology are quite explicitly the result of laws. In the last four decades, the United States and most other wealthy countries have increased the length and strength of patent and copyright protection and other forms of intellectual property.The United States has extended patent duration from 17 years from the date of issuance (less in some sectors) to 20 years from the date of filing, with generous extension provisions to offset delays in processing. Copyrights have been extended from 55 years from the death of the author to 95 years. Perhaps more importantly, the scope of patentable items has been extended to include life forms, software, and business methods. In addition, enforcement provisions have been enhanced to deter unauthorized use of protected material.

The rationale for stronger intellectual property rules is to increase the incentive for research and creative work, which is supposed to lead to more rapid growth. It questionable whether this strengthening has led to accelerated growth (Baker 2016b), but even if it did, we would be looking at a trade-off, not an unchangeable course of technology. In other words, we could decide to accept a somewhat slower pace of innovation, if it also meant less upward redistribution in the form of patent and copyright rents from the rest of society to the small group of people in a position to benefit from them. Unfortunately, this discussion never takes place.

There is a huge amount of money at stake in this area. In the case of prescription drugs alone the United States will spend more than $440 billion in 2017 (2.3 percent of GDP) for drugs that would likely cost less than $80 billion if sold in a free market without patents and related protection. Weaker protections, or even better, an alternative mechanism for financing research, could mean substantially lower drug prices, providing a boost to real wages. There is a similar story with medical equipment, software and many other sectors of the economy.

A very substantial portion of the flows of national income is now determined by intellectual property rules. These should be areas of public policy debate. As it is, there is almost no discussion of the trade-offs between growth and equality in strengthening intellectual property rules (if such a trade-off exists at all), nor the use of alternative mechanisms for financing innovation and creative work.

The Financial Sector

The size of the financial sector has exploded in the United States and most other wealthy countries in recent decades. The core financial sector (securities and commodities trading) went from 0.49 percent of GDP in 1970 to 2.03 percent of GDP in 2015. Many of the highest earners in the United States are in the financial sector. Experienced traders at the major banks often earn more than $1 million a year. Successful hedge fund and private equity partners can make tens of millions or even hundreds of millions of dollars a year. There is certainly a plausible case that these high earnings are largely rent extracted from the rest of the economy, as there is little evidence of a growth premium associated with the expansion of the financial sector.

In fact, recent research has found a U-shaped pattern between the growth in the relative size of the financial sector and the growth rate of the economy (Cecchetti and Kharroubi 2012; Sahay et al. 2015). The logic is that at low levels of development, a larger financial sector boosts growth by facilitating the allocation of capital from savers to investors. However after the financial sector reaches a certain share of output, the additional resources devoted to the sector act as a drag on growth. The sector pulls highly skilled individuals out of areas where they could be more productive. It can also make it more difficult for firms to obtain capital since the financial sector competes with other sectors for funds.

If this story is accurate, then the failure to have policies to rein in the financial sector have both impeded growth and redistributed income upward. Some of these policies would be straightforward. For example, policies that either put an end to banks and other financial institutions that were too big to fail, or forced them to pay premiums that fully reflected the value of this implicit insurance, would be both growth enhancing and reduce inequality. A tax on financial transactions, which would be comparable to sales or value-added taxes in other sectors of the economy, would hugely reduce the income gained from short-term trading. (Standard estimates of trading elasticity imply that the full cost of the tax would be borne by the industry in the form of lower trading volume, with the total cost of trading for end users being little changed by the tax.)

Private equity and hedge funds in the United States have prospered at the expense of public and private pension funds. These pensions have often paid fees that have not been justified by an increase in returns. Policies that require full transparency on fees and returns could reduce the money siphoned off by the big actors in this area.

There is a longer list of policies that might be useful in reining in finance in the United States and elsewhere. However this is clearly an area where many are drawing very high incomes with little apparent benefit to the economy. It is understandable that less highly paid workers would be resentful.

Corporate Governance

The corporate governance process in the United States has become incredibly corrupt. The CEOS and top management have enormous control over who sits on the boards of directors that ostensibly oversee their performance and hold down their pay. Being a director is an incredible cushy job that typically pays hundreds of thousands of dollars a year for very limited work. Directors who are nominated for re-election are almost never defeated, with a win rate of more than 99 percent.

Given these circumstances, directors have almost no incentive to pick fights with top management and their co-directors by asking simple questions like, “could we get someone just as good for half the pay?” As a result, CEO pay in the United States has soared in the last four decades, going from roughly 30 times the pay of a typical worker to well over 200 times the pay of ordinary workers.

Soaring CEO pay also has important spillover effects. The pay of other top managers has also risen hugely relative to the pay of ordinary workers. In addition, the pay of top executives in the non-corporate sector has also risen relative to the pay of ordinary workers. It is now common for university presidents or heads of non-profit hospitals or charities to earn in excess of $1 million a year. While this is much more of a problem in the United States than in other wealthy countries, the excessive pay of CEOs in the United States is putting upward pressure on the pay of CEOs elsewhere.

The key to reining in CEO pay is to change the rules on corporate governance to ensure that directors have incentive to limit the pay of top executives. Governments do write rules of governance (current rules largely focus on protecting minority shareholders), so this is a question of changing rules, not putting rules in place where none existed.

Governments could limit voting on directors and other issues to shareholders who directly vote their shares. (A major problem in the current system is that a large percentage of shares are voted by asset managers who have little direct stake in the performance of the shares, and often have befriended management.) There could also be penalties for directors attached to the “Say on Pay” votes that are now required in the United States and United Kingdom. For example, the directors could lose half of their stipend if a CEO pay package was voted down by shareholders.

There is obviously a much longer list of ways to change the incentives for corporate directors so that they do actively try to contain the pay of CEOs and other top executives. This should be a major focus of public policy, since it is difficult to believe that shareholders and the economy are getting returns from today’s CEOs relative to the CEOs from four decades ago, that are proportionate to the increase in their salaries.

Protections for Doctors and Other Highly Paid Professionals

The average pay of doctors in the United States is more than $250,000 a year. This is more than twice as much as their counterparts in other wealthy countries. Doctors are able to earn this much because they are largely protected from foreign and domestic competition. The protection from foreign competition is quite explicit: doctors are prohibited from practicing in the United States if they have not completed a U.S. residency program. This means that many highly qualified doctors in Canada, Europe, and elsewhere, are prohibited from practicing in the United States. With more than 800,000 doctors in the United States, the potential savings from getting doctors wages down to the level of other wealthy countries is close to $100 billion annually, more than 0.5 percent of GDP.

There are similar restrictions prohibiting foreign dentists from practicing in the United States. Dentists must graduate from a U.S. dental school. (Since 2011 graduates of Canadian dental schools have also been allowed to practice in the United States.)

It is difficult to believe that trade negotiators could not agree upon a set of standards that would allow foreign trained professionals to practice in the United States after meeting an educational standard and passing proficiency tests to prove their competence. If this were a focus of trade policy, it could provide an enormous boost to growth in the United States, by lowering the cost of health care and other services, while also equalizing the distribution of income.4

Highly paid professionals have also benefited by imposing restrictions on the scope of practice of lesser trained, and lower paid, professionals, that ensures more work for themselves. For example, many states prohibit nurse practitioners from prescribing medicine without the authorization of a doctor, even though there is no evidence of worse outcomes in the states that allow for this practice. Similarly dentists have pushed for state laws that restrict the practice of dental hygienists. Many sectors of the economy, such as trucking and air travel, have been subject to deregulation that has put substantial downward pressure on the wages of workers in these sectors. It is necessary to have the same effort to reduce the regulations that protect the incomes of the most highly paid workers.

Summing Up a Progressive Populist Agenda

It is indisputable that there has been a massive upward redistribution of market incomes in the United States and most other wealthy countries over the last four decades. I have argued that this upward redistribution has been largely due to policy choices, not the natural development of globalization technology. The paper outlines five specific areas in which alternative policies can be put in place to counteract these developments.

While policies in each of these areas can have a substantial impact, the interactive effect is likely to amplify their effect. For example, there are more than 850,000 active physicians in the United States, the vast majority of whom are in the top 2.0 percent of the wage distribution. (The U.S. has roughly 150 million people working in 2017.) If their pay were cut 40 to 50 percent, it would place substantial downward pressure on the pay of the rest of the top 2.0 percent. Similarly, if a financial transactions tax reduced trading volume and revenue by 50 percent (around $100 billion a year) the loss of many extremely high paying jobs would substantially reduce the number of job openings with pay in excess of $1 million a year. In this way, attacking high earners through a variety of mechanisms, as outlined above, can have the same spillover effect on wages at the top end as exposing manufacturing workers to competition from low-paid workers in the developing had on the wages of workers in the middle and bottom.

The broader story is that the market can be structured differently than is now the case in order to generate less inequality. Arguably this can be done in ways that actually increase growth, so there is not tradeoff between growth and inequality. We cannot reasonably expect the public to support economic policies which they do not see as giving them a fair share of the benefits from growth. For this reason, it is essential to look to ways in which the current path can be altered to produce more broadly based gains. The failure to do so is not likely to lead to a political environment that many of us will find very appealing.

It is also worth mentioning that broadly based prosperity in rich countries is likely to be more conducive to growth in developing countries. This is both true in a narrow economic sense and also due to the political environment created. In a narrow economic sense, if rich country GDP is 10 percent lower due to bad macroeconomic policy, this means that rich countries will import substantially less from the developing world. A falloff in imports due to weak economic growth has the same impact as reduced imports due to tariffs or other protectionist measures. It is also worth noting that developing countries share in the benefits of innovation from rich countries, assuming that they are not unnecessarily walled off by restrictive intellectual property rules. This means greater technological dynamism by rich countries will also benefit developing countries.

In terms of the political environment, as president, Donald Trump seems determined to give the world a case study in how right-wing populism can be bad news for the developing world. He has indicated a willingness to arbitrarily alter longstanding trade agreements, with little concern for the impact on our trading partners. His first budget calls for large cuts in foreign aid, including an end to any assistance to the developing world in dealing with climate change. And, he proposes restrictions on immigration that reverse practice in the United States, even if not necessarily changes in the law. This is all being done with little, if any, regard for the impact on the countries from which people are emigrating.

For these reasons developing countries have a clear stake in having rich countries pursuing policies that have economic benefits for the bulk of the population. If we continue on the current course, the outcomes are not likely to be very good.

References

Autor, David, David Dorn, Gordon Hanson, Kaveh Majlesi. 2017. “A Note on the Effect of Rising Trade Exposure on the 2016 Presidential Election.” MIT Working Paper, rev. January 2017. http://economics.mit.edu/files/12418.

Baker, Dean. 2002. “The Run-Up in Home Prices: Is it Real or Is it Another Bubble?” Washington, D.C.: Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/publications/reports/the-run-up-in-home-prices-is-it-real-or-is-it-another-bubble.

Baker, Dean. 2016a. Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer. Washington, D.C.: Center for Economic and Policy Research. http://deanbaker.net/images/stories/documents/Rigged.pdf.

Baker, Dean. 2016b. “Working Paper: Rents and Inefficiency in the Patent and Copyright System: Is There a Better Route?” Washington, D.C.: Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/publications/reports/working-paper-rents-and-inefficiency-in-the-patent-and-copyright-system-is-there-a-better-route.

Baker, Dean and Jared Bernstein. 2013. Getting Back to Full Employment: A Better Bargain for Working People. Washington, D.C.: Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/documents/Getting-Back-to-Full-Employment_20131118.pdf.

Baker, Dean and Sarah Rawlins. 2017. “The Clinton-Trump Vote and the Socioeconomic Progress of the White Working Class.” Washington, D.C.: Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/blogs/beat-the-press/the-clinton-trump-vote-and-the-socioeconomic-progress-of-the-white-working-class.

Blanchard, Olivier, and Daniel Leigh. 2013. “Growth Forecast Errors and Fiscal Multipliers.” IMF Working Paper No. 13/1. International Monetary Fund.

Cecchetti, Stephen G. and Enisse Kharroubi. 2012. “Reassessing the Impact of Finance on Growth.” Basel, Switzerland: Bank of International Settlements. BIS Working Paper No 381. http://www.bis.org/publ/work381.pdf.

DeLong, Bradford and Larry Summers. 2012. “Fiscal Policy in a Depressed Economy.” Brookings Papers On Economic Activity, Spring, pp. 233-297.

Guo, Jeff. 2016. “Death predicts whether people vote for Donald Trump.” Washington Post, March 4. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/03/04/death-predicts-whether-people-vote-for-donald-trump/.

International Monetary Fund. 2009. World Economic Outlook Database, April 2009. International Monetary Fund. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2009/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=61&pr.y=12&sy=2007&ey=2014&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=156%2C158%2C132%2C112%2C134%2C111%2C136&s=NGDP_RPCH&grp=0&a=.

International Monetary Fund. 2010. World Economic Outlook: October 2010. International Monetary Fund.

International Monetary Fund. 2016. World Economic Outlook Database, October 2013. International Monetary Fund. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=71&pr.y=5&sy=2011&ey=2021&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=156%2C158%2C132%2C112%2C134%2C111%2C136&s=NGDP_RPCH&grp=0&a=.

Monnat, Shannon, 2016. “Deaths of Despair and Support for Trump in the 2016 Election,” The Pennsylvania State University, Department of Agricultural Economics, Sociology, and Education Research Brief, 2016-12-04.

OECD. 2015. Income Inequality: The Gap Between Rich and Poor. Paris, France: OECD.

Sahay, Ratna et al. 2015. “Rethinking Financial Deepening: Stability and Growth in Emerging Markets.” Washington, D.C.: IMF. IMF Staff Discussion Note. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2015/sdn1508.pdf.

Figures

[1] The projections from 2008 only run to 2013. The figure assumes that the growth rate projected for 2012 to 2013 continues for the next three years.

[2] This discussion draws heavily from Baker (2016a). The arguments are laid out more completely, with a fuller set of references.

[3] It would be desirable to have a system of compensation so that developing countries were compensated for the loss of professionals that they had paid to train. It should not be difficult to design a system whereby low income countries received payments that were large enough to train two or three professionals for each one that came to the United States. This would ensure that they shared in the gains from this process.