February 23, 2017

February 23, 2017 (Latin America Data Byte)

By David Rosnick

After a year of zero growth over 2014, Brazil’s economy shrank nearly 6 percent in 2015, and another 3 percent over the first three quarters of 2016. Gross Domestic Product in the third quarter was only 0.7 percent greater than in the same period of 2010. Yet over those six years, the working-age population grew about 8 percent.

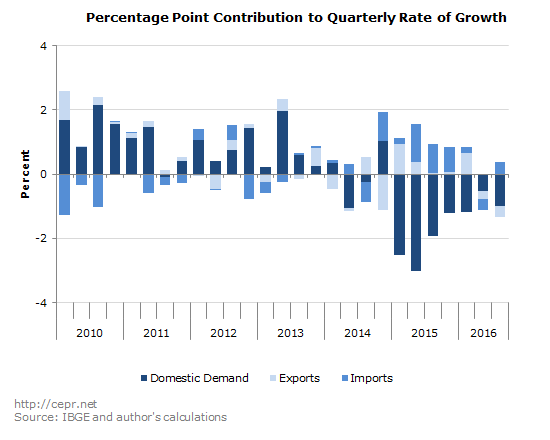

Domestic demand has collapsed. From its peak at the start of 2014, Brazilian demand for real goods and services has fallen nearly 11 percent, subtracting 4 percentage points annualized from real GDP growth.

About 12 percent of demand for Brazil’s output came from foreign sources. Such real exports rose 7 percent over the same period, adding only slightly to annualized GDP growth. However, real exports fell in the second and third quarters of 2016.

As demand has fallen, so has Brazil’s demand for foreign goods and services. Since the start of 2014, the contribution of reduced imports to GDP has been about 1.5 percentage points annualized, with imports having fallen by 24 percent over the period. This reflects both reduced demand for foreign goods, and substitution for domestic sources. Import prices have grown 18 percent over the ten quarters.

The more recent collapse in growth has been very broadly based throughout the economy. Agriculture, which represented 6 percent of Brazil’s value added at the start of 2015, has fallen 11 percent. Industry, which was 22 percent of value added, has fallen 8 percent — including a 12 percent fall in manufacturing and a 10 percent fall in construction. The only industry subsector with real growth over the most recent six quarters has been utilities — growing nearly 5 percent, but accounting for little more than 2 percent of total value added. Services, likewise, have fallen 5 percent since the first quarter of 2015 despite a 0.4 percent rise in public services. The losses were led by trade and transportation — each falling 11 percent over the last six quarters, and 16 and 14 percent, respectively, over the last 10.

Despite the economic weakness, the Central Bank of Brazil began cutting its benchmark Selic rate only last quarter — in the face of sharp economic collapse ? from the 14.25 percent where they had held it since mid-2015. This continues to represent tremendously tight monetary policy.

Headline inflation ran as high as 11.3 percent over 2015. However, this was dominated by volatile food and energy prices. Core inflation ran only 8 percent in the period and fell past 7 percent for the 12 months ending in December. By comparison, when the economy of the United States shrank similarly in 2008 and into 2009, the Fed cut rates from 5.25 percent to zero.