December 03, 2015

Matt Yglesias is trying to convince people that we should not be mad at Alan Greenspan, the Bush administration economic policy team, and the economics profession for missing the housing bubble that sank the economy. He says that “financial bubbles are much harder to spot than people realize” and argues that the subsequent history shows that I actually was wrong in identifying a housing bubble in 2002.

There are two important points that need to be made here. First, my claim has always been that identifying asset bubbles that move the economy is in fact easy. This both narrows the scope for observation and also gives us more evidence against which to check the assessment. In terms of narrowing the scope, I would not hazard a guess as to whether there is a bubble in the market for platinum or barley. You would need to do lots of homework about these specific industries and also the prospects for related sectors that could provide platinum or barley substitutes, as well as the industries that use these commodities as inputs.

In looking at the housing market in 2002, it was possible to see that sale prices had diverged sharply from rents. While sale prices had already risen by more 30 percent compared with their long-term trend, rents had gone nowhere. Also, the vacancy rate in the housing market was at record highs. This strongly suggested that house prices were not being driven by the fundamentals. (Weak income growth also seemed inconsistent with surging house prices.) If families suddenly wanted to commit so much more of their income to housing, why wasn’t it affecting rents and why were so many valuable units sitting empty?

And, the housing market was clearly driving the economy. Housing construction was reaching a record share of GDP. This was not something that would be expected when most of the baby boom cohort was looking to downsize as kids moved out of their homes. Also, the housing wealth created by the bubble was leading to a consumption boom, driving savings rates even lower than they had been at the peak of the stock bubble.

I’ll confess that I did not expect the bubble to continue as long as it did. I learned from my experience with the stock bubble that the timing of the bursting is pretty much unknowable, but it never occurred to me that Greenspan and other financial regulators would allow the proliferation of junk mortgages to the level they reached in 2004–2006, the peak bubble years.

Contrary to the “who could have known?” alibis told by the folks setting policy, the abusive mortgages being pushed at the time were hardly a secret. The financial press were full of accounts of NINJA loans, where “NINJA” stands for no-income, no job, and no assets. Anyone who cared to know, realized that millions of mortgages were being issued that could only be supported if house prices continued to rise.

Anyhow, it was inexcusable for the folks at the Fed, at the Council of Economic Advisers, and other policy posts to have been blindsided by the bubble and the damage that would be caused by its collapse. If dishwashers had failed so miserably at their jobs, they would all be unemployed today. Fortunately for economists, they don’t have the same level of accountability.

But Matt points out that inflation-adjusted house prices today are as high as when I began talking about the bubble back in 2002, a point also frequently made by readers of this blog. So was I wrong then or is there a new bubble today? (He also has me warning about high house prices in 2010, when they were lower than current levels.)

In response, I would say there were events that I had not foreseen, specifically that the U.S. and other wealthy countries would decide it was a clever idea to have a massive turn to austerity in 2010 when their economies were still far from recovering from the downturn. This turn to austerity made the recession far longer and deeper than I had envisioned at the time.

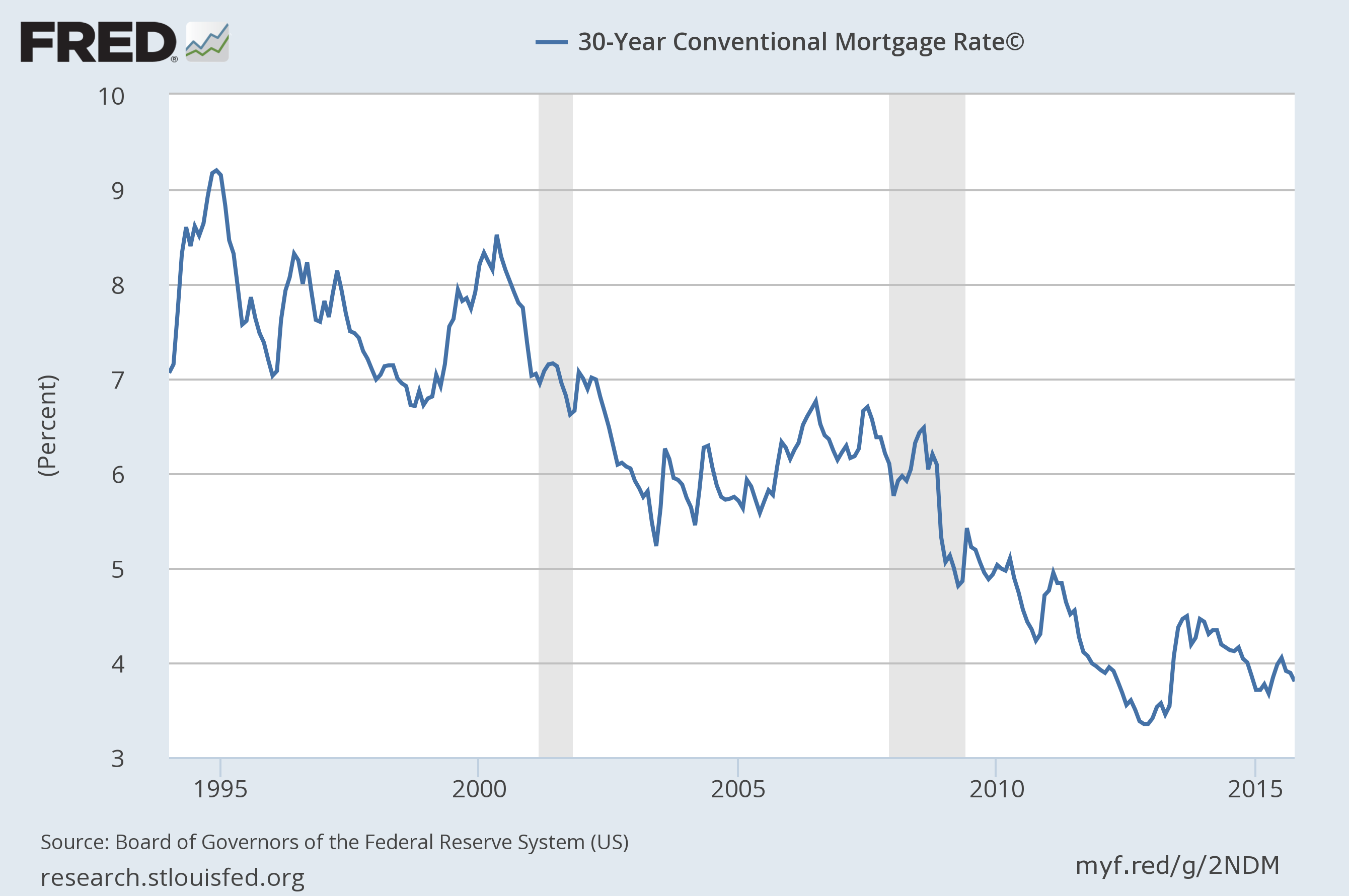

This matters for house prices, since the continuing weakness of the world economy has meant far lower interests than I or others had expected. Back in 2010, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds would be 5.5 percent by now. That would imply a mortgage interest rate over 7.0 percent. Instead, the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds is hovering near 2.2 percent with mortgage interest rates around 4.0 percent. Here’s the record on mortgage interest rates over the last two decades.

Like CBO and other economists, I had been expecting the economy to return to something closer to full employment (sorry Chairperson Yellen, we ain’t there yet) and mortgage interest rates to look something like they did in the late 1990s. On this I was clearly wrong. While house prices are not hugely sensitive to interest rates, there is a big difference between a 7.0 percent rate and the 4.0 percent rate we are now seeing. And almost all of that gap is in real interest rates, inflation was not much different in the 1990s than it is projected to be over the next decade.

Does that mean that I and others can’t predict bubbles in the housing market? To take an overblown analogy, suppose that a massive explosion had destroyed half of the housing in Washington, D.C., but miraculously left the population and our leading industry (lobbying) unaffected. This would be expected to lead to a surge in house prices. Would this mean I was wrong if I said house prices were high in DC in the pre-explosion era? I leave that one to the philosophers out there.

One last point, Yglesias refers specifically to the D.C. market, which both he and I have some occasion to know directly. House prices, and especially condo prices, have been rising very rapidly in recent years. There are many new buildings with 2-bedroom condos selling in the $700k range. My view is that this market is certainly experiencing a bubble. I base this view on the fact that it not very difficult to build a 100 unit condo building and that many developers seem to be doing this right now. And also, even in Washington there are only a limited number of people who can afford to pay $700k for a two-bedroom condo.

But I really don’t want people to take my advice on this one. After all, as long as the market for condos stays hot, builders will put up more units. Eventually the bubble will burst and the builders still holding unsold units or in the process of constructing them, along with the recent buyers, will take a beating. But this should mean that the abundance of units on the market will make prices more affordable for everyone else. Given the current state of national politics, this may be the best hope for any sort of downward redistribution on the horizon.

Comments