November 17, 2015

Josh Barro had a good discussion of the impact of longer life expectancy on the finances of Social Security. The basic point is the program will cost more money. There are a couple of points that are worth a bit more discussion and one mistake that should be corrected.

Starting with the mistake, Barro ends his piece by saying that the last major overhaul to Social Security was carried through by a bipartisan commission in 1985. Actually, the recommendations of the Greenspan commission were approved by Congress in 1983.

The first point worth some additional comment is Barro’s reference to the chained Consumer Price Index (CCPI), which he says most economists view as a more accurate measure of the rate of inflation. President Obama and others have proposed using the CCPI to index post-retirement benefits. This would reduce average benefits by around 3 percent, since the CCPI shows a rate of inflation that is 0.2–0.3 percentage points lower than the CPI currently being used. This reduction would be cumulative, so that after ten years a retiree would receive a benefit that is between 2–3 percentage points lower than under the current system. After 20 years the benefit reduction would be between 4-6 percent.

While the CCPI is arguably more accurate as a measure of the rate of inflation seen by the population as a whole, economists do not have evidence of whether this is true for retirees. Older people have different consumption patterns than the rest of the population. They may also change their consumption less in response to changes in price than the rest of the population. (The difference between the CCPI and the currently used CPI is that the CCPI picks up the effect of changes in consumption patterns due to price changes.)

If the concern is in fact accuracy, Congress could instruct the Bureau of Labor Statistics to construct a full elderly CPI that monitored the actual purchasing patterns of the elderly. Of course if the point is to find a politically easy way to cut benefits, then the CCPI is adequate for the task.

The second point is that the impact of any future tax increases depends in large part on wage growth. The payroll tax was increased by 3.0 percentage points in the decade of the 1950s, 3.4 percentage points in the 1960, 1.76 percentage points in the 1970s, and 2.24 percentage points in the 1980s. Few, if any, politicians lost their jobs because of these increases, because for most of this period real wage growth swamped the impact of higher taxes. (That was not the case in the 1980s, when wages for most workers first began to stagnate.)

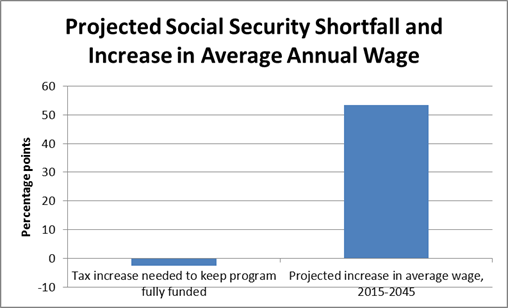

If most workers again share in the benefits of productivity growth, then wage growth going forward will hugely exceed any plausible tax increases associated with Social Security. (One of the reasons the program is projected to face a shortfall is that such a large share of wage income now goes to high end earners. It escapes taxation since it is over the $118,500 cap on taxable income.)

Source: Social Security Trustees Report, 2015.

It is important to include wage growth in any discussion of Social Security since it has such a large impact on the finances of the program and also the ability of workers to absorb tax increases.

Comments