May 21, 2015

I see that Niall Ferguson is again pushing the case that the austerity pursued by the Cameron government in 2010 was both necessary and good. This can be a useful opportunity to show why the history since the Conservatives took power does not support this claim, even though they managed to get re-elected.

To quickly summarize Ferguson’s case, he argues that the turn to austerity was a matter of necessity, not choice. The U.K. had a high and rising debt burden. Furthermore, inflation was increasing and reaching dangerous levels. So it was necessary for the government to take quick action to reduce the deficit to keep the economy on a stable path. However, once on this course the economy quickly rebounded. The government’s actions restored business confidence leading to strong investment and growth.

Let’s start with the debt story. Ferguson cites a study from the Bank of International Settlements and argues that the government faced a much worse debt picture than other countries:

“The baseline scenario for the UK at that time was that, in the absence of fiscal reform, public debt would rise from 50% of GDP to above 500% by 2040. Only Japan was forecast to have a higher debt ratio by 2040 in the absence of reform.”

Okay, that sounds pretty bad. Of course there is a long time between 2010 and 2040 to deal with rising debt if it becomes a burden on the economy, but there are two points that argue strongly there was no need for the Cameron government to be concerned about a financial panic sinking the country.

The first is simply that long-term interest rates were still quite low by historic standards. At the time the Cameron government took power, the yield on 10-year bonds was hovering near 4.0 percent. While this may seem high compared to the interest rates we have seen more recently, it was well below the rates the U.K. faced before the recession. With an inflation rate near 3.0 percent, this implied a real interest rate of just 1.0 percent. That was higher than was desirable for a country coming out of a severe recession, but hardly a usurious burden.

The other point comes from the country that is supposed to be the warning flag in Ferguson’s account. Japan did not go the route of austerity, in fact since Shinzo Abe came to power at the end of 2012 the country has quite explicitly taken the path of stimulus. It has run large deficits adding to its world leading debt-to-GDP ratio. Yet, these deficits have not led to soaring interest rates and financial panic. Currently the interest rate on 10-year Japanese bonds is 0.41 percent. If Japan had this much room for expansionary policy then it’s hard to see how the U.K. could have faced any near-term constraints.

It is worth noting that Cameron came to power at the high-point of the famous Reinhart-Rogoff spreadsheet error. Their analysis purported to show that there was a cliff where countries with debt-to-GDP ratios above 90 percent experienced markedly slower growth than countries with lower debt burdens. There were good reasons for questioning this conclusion at the time, but subsequent work has shown that the cliff disappears in the corrected spreadsheet. Furthermore the causation runs primarily from slow growth to high debt-to-GDP. It would be generous to accept that some people believed the mistaken spreadsheet back in 2010, but there is no basis today for saying the U.K faced any imminent debt crisis.

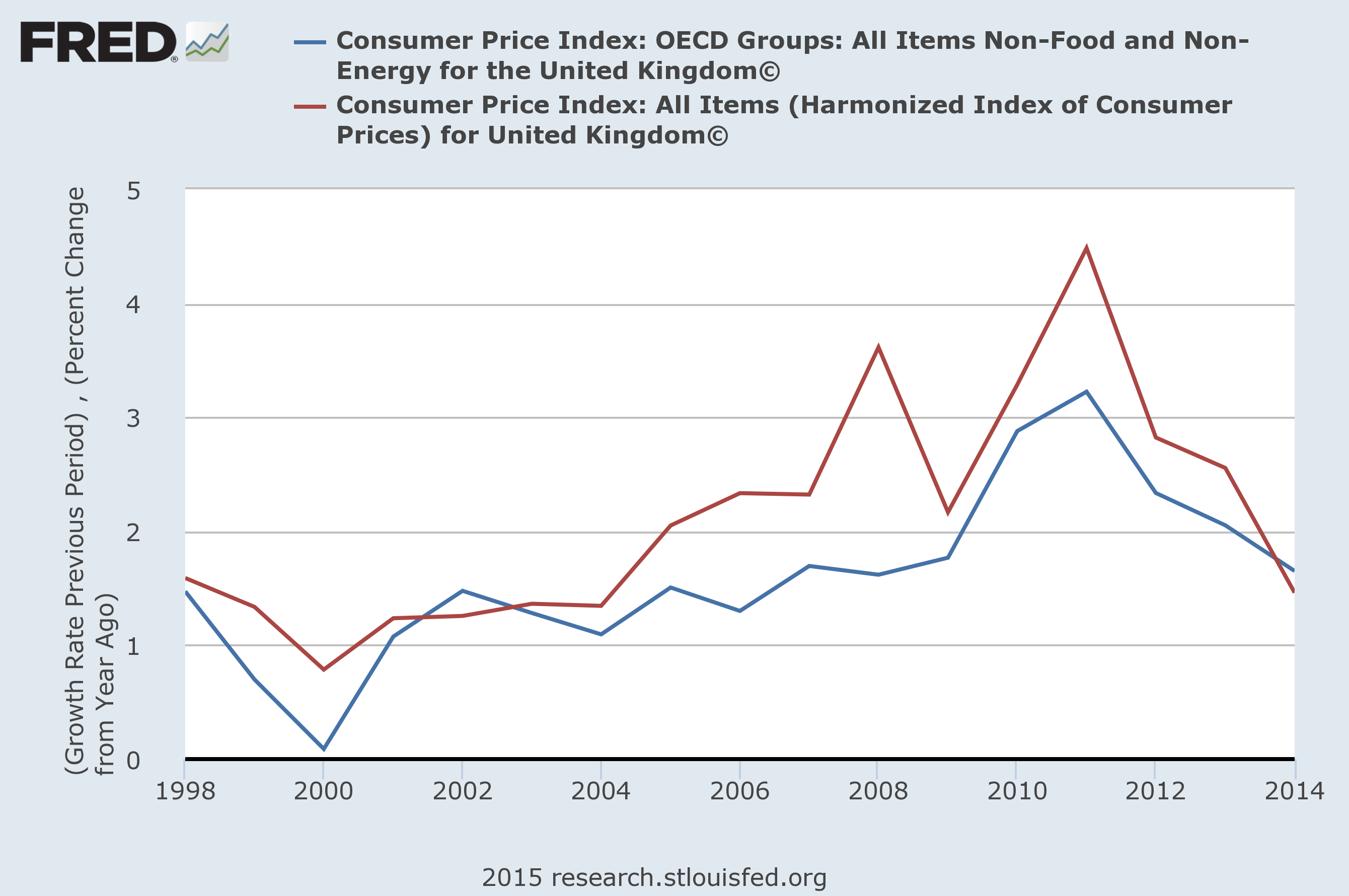

There was also not much more basis for believing that inflation was in danger of getting out of control back in 2010. Ferguson tells us:

“Inflation was above the Bank of England’s target. From 2000 until 2008, the inflation rate had crept upward, from below 1 percent to 3.6 percent. Among G-7 countries, only the US rate was higher in 2008; but, whereas US inflation cratered when the crisis erupted, the UK rate remained stubbornly elevated, peaking at 4.5 percent in 2011.

The headline inflation number in the U.K. had risen to 3.6 percent in 2008, but this was primarily the result of the world-wide surge in oil and other commodity prices. The core inflation was under 2.0 percent for the whole period, except for a short time in 2008. The overall inflation rate fell sharply in 2009, when oil prices fell back from 2008 peaks. Furthermore, there is no evidence of concern that inflation was about to spiral out of control. If this had been the case, it is difficult to see why investors would be lending the government money long-term at just a 4.0 percent interest rate.

The inflation rate did tick up at the end of 2009 and start of 2010. The most likely culprit was the sharp decline in the pound relative to the euro and the dollar. This was actually a positive development for an economy operating well below its potential level of output, even if it did lead to a one-time rise in the inflation rate. The drop in the pound was a major factor in the decline in the current account deficit from 3.7 percent of GDP in 2008 to 1.7 percent of GDP in 2011. This has roughly the same effect on employment and growth as a stimulus package equal to 2 percent of GDP (@$360 billion a year in the U.S. economy today).

Overall inflation did eventually peak at 4.5 percent in 2011, as Ferguson indicates, but this was because of the value-added tax that was part of the Cameron government’s austerity package. This raised the prices of goods and services, leading to a one-time jump in the inflation rate. If we are supposed to be troubled by this 4.5 percent inflation rate, then austerity was the problem, not the solution.

The next issue is the extent to which the U.K. economy recovered after the initial dose of austerity and the cause of the rebound. Taking the latter issue first, Ferguson is anxious to claim that business confidence was the key. He shows a measure of business confidence which rises substantially following the implementation of Cameron’s austerity package.

The problem with this story is it’s not clear that this confidence had much effect on the economy. Business investment did not exactly surge when presented with the Conservatives’ program. In 2012 real business investment (Table 1.1.8) was up 10.4 percent from 2010 levels and was still down by 2.0 percent compared to the 2008 level. That’s not terrible, but in the less austere U.S. (where confidence was presumably not boosted to the same extent) the increase from 2010 to 2012 was 15.7 percent. This left investment virtually even with its 2008 level, although still down by 0.8 percent compared with 2007.

There are two other factors that likely spurred the modest rebound the U.K. has seen in the last two years. The first is the relaxation of austerity. According to the I.M.F’s data, the structural deficit declined from 8.1 percent of GDP in 2010 to 3.6 percent of GDP in 2013. This drop of 4.5 percentage points of GDP would be equivalent to a reduction in the annual deficit in the current U.S. economy of roughly $800 billion. The structural deficit then rose modestly to 4.2 percent of GDP in 2014 and is projected to remain roughly constant at 4.0 percent of GDP in 2015. So the period when reductions in the deficit would be putting a crimp on growth had ended by 2013.

The other factor was the return of the housing bubble. After falling sharply in 2008 and 2009, house prices began to rise again at the end of 2012. While the ratio of house prices to income is still below the peaks of the bubble, it is now almost back to where it was in 2006. The wealth effect from this surge in house prices has helped to spur consumption, with households in the U.K. again spending more than their income, leaving them with a negative saving rate (Table 1.1.5). Construction has also bounced back, with the current level of construction (Table 2b) more than 60 percent higher than the average for the last four years prior to the 2001 recession. As folks who were alive in 2008 can attest, this is not a story that is likely to end well.

Finally, it seems more than a bit bizarre for anyone to be bragging about the track record of an economy that has grown at less than a 2.0 percent annual rate over the last five years. This performance is especially dismal given the large output gap created by the downturn. Such gaps typically create the basis for rapid growth. For example growth in the U.S. economy averaged 5.4 percent in the 3 years following the 1981-82 recession and 5.2 percent for three years following the 1974-75 recession. GDP growth averaged almost 11 percent in the years 1934-1936.

In Cameron’s defense, there was no major country that had this sort of robust rebound following the 2008–2009 crisis. I would argue that this is due to the fact that no government was prepared to run deficits of the magnitude necessary to get back to full employment, with the possible exception of the new Japanese government. But it’s not necessary to directly answer that question to assess the Cameron growth record, we have a simple mechanism for grading him on a curve.

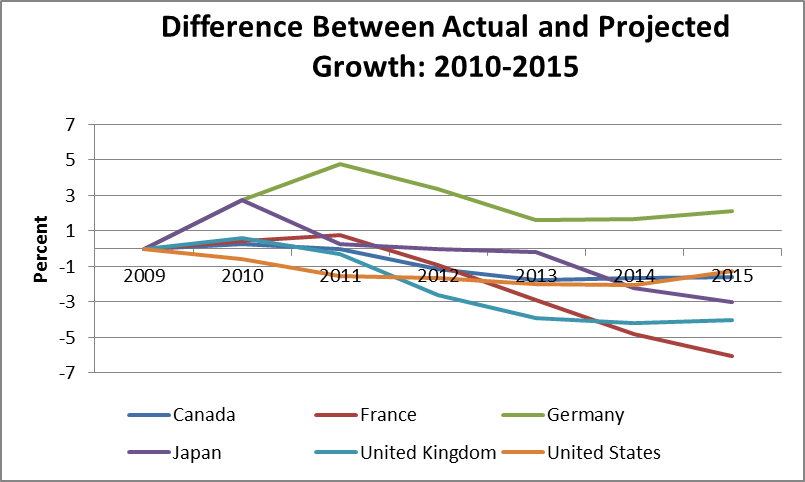

In April of 2010 the I.M.F. came out with their growth projections that accompany the World Economic Outlook. These were the last projections made for the U.K. before Cameron took power. They presumably were made based on all available information about the U.K.’s economy and the policies then expected to be pursued by the Labor government. We can then compare the U.K. actual growth record over the last five years with what the I.M.F. had projected back in 2010. We can make the same comparison for other major economies to see whether Cameron did better or worse.

These projections are never perfect, but the errors tend to be highly correlated. In other words, if they overstate growth for the U.K., they are likely to also overstate growth for Germany, Canada, the U.S. and most other wealthy countries. For this reason, they provide a simple and unbiased test of whether the Cameron government’s policies improved or worsened the pace of growth compared to the less austere policies the Labor government was pursuing. (This methodology is a ripoff of an I.M.F. paper demonstrating the effectiveness of stimulus by comparing their forecast errors with the extent of deficit reduction.)  Source: I.M.F. and author’s calculations.

Source: I.M.F. and author’s calculations.

As can be seen, through 2014 the U.K. comes in second to last, edging out France which also was forced to undergo serious austerity treatment by virtue of being in the euro zone. (I have included the projection for 2015, which makes Japan’s performance look relatively bad.) While Germany is the only country that did better than projected, the U.S., Japan, and Canada, were all down by roughly two percentage points of GDP compared with the 2010 projection, compared with the U.K.’s shortfall of 4.2 percentage points. (Including Italy would have given the U.K. another country it could beat.)

Anyhow, if the U.K. growth record is one worth boasting about, then we have defined down in a big way the standard of success in economic policy. That looks like a serious case of the soft bigotry of low expectations.

Correction: The piece originally said the core inflation rate fell in 2009 in addition to the headline inflation rate.

Comments