February 03, 2014

Recently some opponents of an increase in the minimum wage have argued that we are using an inaccurate measure of inflation when we say the 1968 minimum wage would be equal to about $10.00 an hour in today’s prices. They argue that if we use the Personal Consumption Expenditures Deflator (PCE) to measure inflation –instead of the Consumer Price Index (CPI-U, modified slightly to reflect current methods back as far as 1968– we would need a minimum wage of just $8.50 an hour to have the same purchasing power as in 1968. Furthermore, if we take the average value of the minimum wage over the years 1960-1980, the current minimum wage of $7.25 would already be roughly equivalent in purchasing power.

This argument raises several interesting points about the measure of inflation. It also calls attention to an important point about government policy toward the minimum wage. In the years prior to 1968, the minimum wage was deliberately raised by more than enough to keep pace with purchasing power. In the three decades from 1938 to 1968 Congress raises the minimum wage by enough to keep in step with productivity growth. The intention was to ensure that even workers at the bottom shared in the benefits of economic growth. This issue is worth noting in the current debate.

First, there are three important points about the measure of inflation used to assess the minimum wage:

- Unlike the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index (CPI-U-RS, the version of the CPI that approximates the current method of measuring inflation to earlier years), the PCE is not designed as a deflator of cash income.

- There are difficult issues about assessing the cost-of-living over time that have been debated by economists and policy makers. It is not clear that the PCE comes closer to a “true” measure than the CPI-U-RS.

- Congress has not used the PCE for other purposes. For example, if the PCE were applied consistently, the cutoff for income tax brackets would all be around 10 percent lower than is currently the case, raising tax rates relative to the current brackets, which are based on the CPI-U.

Taking these in turn, the CPI-U-RS that economists use to measure the rate of inflation seen by consumers is intended to reflect the portion of their income devoted to the various items they consume. By contrast, the PCE is intended as a price index to assess prices changes for everything that falls into the consumption component of GDP. This leads to some important differences.

For example, the PCE includes a component to measure the portion of consumer expenditures that are covered either by employer-provided health insurance or government provided health insurance, like Medicare. The CPI medical spending component only picks up expenses that are paid by individuals either as directly purchased insurance, premiums on an employer or government plan, or out of pocket expenses.

The PCE also includes many expenses related to the operation of home businesses. For example, the weight of computer in the PCE (0.87 percent) is more than three times larger than its weight in the CPI (0.26 percent). The PCE also includes items that are not a visible part of consumers’ market basket. For example, it includes the value of financial services provided without payment, like free checking accounts for people who maintain a certain minimum deposit. These services accounted for 2.3 percent of the PCE in 2013. The PCE also includes expenditures made by non-profit organizations like private universities or charities. In short, the PCE is not designed to be a measure of the rate of inflation seen by consumers, so its use for this purpose has to be questioned.

There is a second issue as to whether the PCE may still more accurately reflect the rate of inflation experienced by consumers even if it was not designed for this purpose. The biggest methodological difference is that the PCE takes account of the substitutions in consumption, as consumers shift away from items that see rapid rises in price to ones that see less rapid rises in price. This means that if people shift from consuming apples to oranges, because the price of apples rose, then the PCE would decrease the weight of apples and increase the weight of oranges. By contrast, CPI-U-RS would hold the weight of apples and oranges fixed.

Clearly consumers can and do shift their consumption to some extent to protect themselves against price increases. However, it is not clear that all consumers are capable of substituting to the same extent. Research by the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicated that lower income consumers may be able to substitute less than higher income consumers. (It is worth noting that the CPI-U-RS already assumes substantial substitution at lower levels, for example between types of apples or types of oranges.)

The issue of how substitution should be treated in a price index and whether it is the same for all groups is an important one. It certainly has not yet been resolved. While inadequately capturing substitution may lead to an overstatement of inflation, it is also worth noting that there are reasons that the CPI-U-RS may understate the rate of inflation seen by consumers.

For example, people need items in their normal basket of consumption goods, like cell phones, computers, and Internet access, that they would not have needed 30 years ago. All of these items provide enormous benefits, but they also come with additional cost. A person without Internet access in 1980 would not have suffered any hardship; however a person without Internet access in 2014 is cut off from a major means of social communication. It is not clear exactly how new needs should be captured in the CPI, but by missing these items the CPI is almost certainly understating the true increase in the cost of living.

Finally, in using the CPI-U-RS to adjust the minimum wage, President Obama is following the general practice for other items that are indexed, most importantly income-tax brackets. If the PCE had been used to adjust income-tax brackets since indexation first went into effect in 1983, the bracket cutoffs would be close to 10 percent lower than they are today. This means that most people would be paying higher taxes since more of their income would be taxed at a higher rate. If we really believe that the PCE is a better measure for inflation, we should be using it to adjust the income tax brackets as well, not just the minimum wage.

The last point, that taking the whole period 1960-1980 as a basis of comparison, rather than just the peak year of 1968 brings up the important point that the minimum wage used to be increased in step with productivity growth, not just the cost-of-living. In other words, prior to 1968 Congress quite deliberately chose to increase the minimum wage by more than the rate of inflation to ensure that workers at the bottom of the wage distribution got their share of the benefits of economic growth.

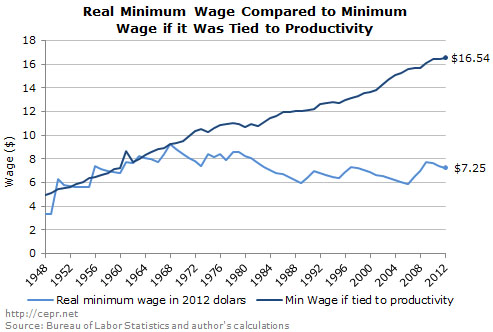

The figure below shows the actual path of the minimum wage since 1948 and where it would be if it had kept pace with productivity over this period. (The measure of productivity growth used in this analysis is more conservative than the published data.)

If we had continued to increase the minimum wage in step with productivity growth its current value would be close to $17 an hour. While it would not be plausible to imagine the government could raise the minimum wage to this amount quickly without having a big impact on employment, there is no obvious reason that we could not over time develop an economy that could support employment at these wages. In any case, it is important to remember that we had once been on path that would have led to a minimum wage that is well more than twice the minimum wage we have today.