September 03, 2012

Robert Samuelson gives President Obama a low grade for his economic performance following his initial six months in office (so do I). Let’s examine the basis for his assessment.

His main complaint is that Obama pushed the Affordable Care Act (ACA) through Congress. Samuelson complained that this distracted the president from focusing on the economy and created uncertainty. Let’s start with the first complaint.

What does it mean to say that the ACA distracted President Obama from the economy? What would Samuelson have had Obama do that he didn’t do because he was distracted? Was there some great policy that would have boosted economic growth that he should have been pursuing had he not wasted time and political capital dealing with the ACA?

That is a serious question. Undoubtedly passing the ACA did take much of his staff’s time and used up enormous political capital, but that by itself doesn’t mean that it came at the expense of policies that might have provided a more immediate boost to the economy. It is necessary to identify those policies and argue that Obama could have pursued them if he had not been occupied by the ACA.

I have my list (more stimulus, work sharing, getting the dollar down, Right to Rent), but I don’t see any reason to believe that these policies would have been pushed more aggressively by President Obama if he had not been wasting time with the ACA. Samuelson doesn’t even give us a list. What is it that he thinks President Obama would have been doing to create jobs and foster growth had it not been for the ACA? Samuelson doesn’t give us any clue.

Turning to Part II, the ACA supposedly created uncertainty and this slowed growth and job creation. This is again one of those throw away lines that makes little obvious sense. First, the ACA has very little impact on employers until 2014. Do we really think that firms were not hiring workers in the summer of 2010 because they might have to pay for their health care or pay a fine in January of 2014?

Think about this one for a moment. A factory is seeing growing demand for its product. A thriving restaurant has more business than it can deal with. Rather than hire the additional employees necessary to meet this demand, these businesses say that they are concerned that in three and a half years they may have to meet the requirements of the ACA.

Does that sound plausible? To throw in one additional possibly relevant factoid, almost 3 percent of the workforce leave their job every month (roughly half voluntarily, half involuntarily). In other words, if our nervous employer is concerned that they will be stuck with unwanted workers when the ACA kicks in on January 1, 2014, they will have ample opportunity to get rid of them before then.

And how bad is the hit? It’s a maximum of $2,000 per worker for firms that employ more than 50 full-time workers. Since it exempts the first 30 workers, the penalty for a firm right at the 50 worker cutoff would be $800 per worker. This would be 40 cents per hour for a full-year full-time worker. There is now a large body of research showing that increases in the minimum wage of 15-20 percent have no measurable effect on employment.

This fine would come to approximately 2.5 percent of the wage of an average full-time full-year worker, assuming that there is no corresponding reduction in wages (as economic theory would predict). How large of an employment effect should we expect when the fines actually take effect in January of 2014? How large of an effect should we expect now?

Furthermore, the impact would not be felt evenly across firms. Most employees already receive health care coverage that would meet the requirements of the ACA. Their employers should not be slowed in expansion from the law. Similarly, many smaller firms are well below the size threshold where the fines would be applicable. These firms also should not be slowed in their expansion plans by the law.

While it is popular among opponents of the ACA to claim that it has slowed hiring, no one has presented any evidence that the firms that would actually be affected by its main provisions have been hiring at a slower pace than the ones that would not be affected. A little evidence would go a long way towards helping their case.

Finally, Samuelson says that we are seeing less investment and less consumption than would be the case if not for the uncertainty created by President Obama’s policy. He thinks this may have slowed job growth by 25,000 a month or so.

Let’s look at this one more closely. Measured as a share of GDP, investment in equipment and software is just a few tenths of a percentage points below its pre-recession level. Given that there is still a huge amount of excess capacity in many sectors of the economy investment is surprisingly high, not low.

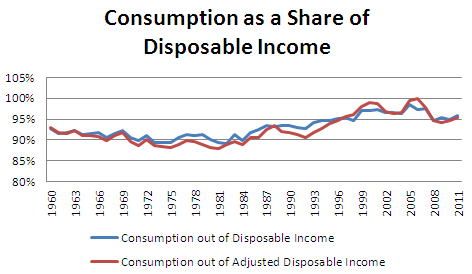

How about consumption? Here’s the consumption share of disposable income. In fact, consumption is also unusually high, not low, relative to disposable income as shown below. (Adjusted disposable income has to do with the statistical discrepancy for those nerds out there.)

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Tables 2.1 and 1.7.5.

The consumption share of income has not risen back to the peaks of the stock or housing bubble, but given the massive loss of wealth, it would be shocking if it did. Furthermore, since a substantial chunk of disposable income is due to tax cuts which are supposed to be temporary, that economic theory tells us should not be spent, we should expect the consumption share of income to be lower than normal, not higher as the graph shows.

In short, it doesn’t seem that Samuelson has much of a case here. It doesn’t look like he’s going to get a very good grade on this column.

Comments